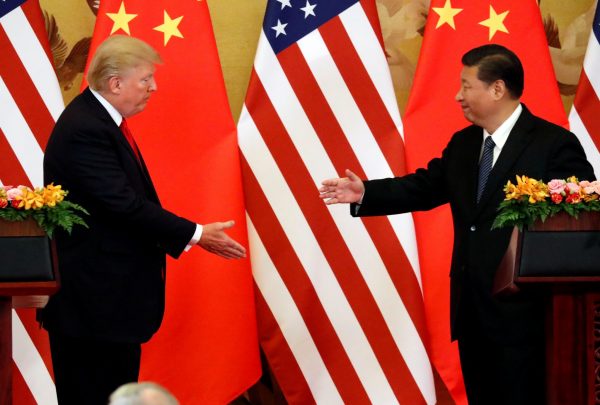

On entering office, US President Donald Trump put several contentious issues with China on the backburner in the hope of achieving his primary goal — North Korea’s denuclearisation. When that failed, the frontburner of US–China relations became crowded with previously repressed issues.

Several of these — US freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea, talk of steel and aluminium tariffs, weapons sales to Taiwan, threats to tighten technology and investment flows as well as secondary sanctions on Chinese entities — threaten to become serious problems if not managed in a more careful manner than the Trump administration is currently demonstrating.

So what might the United States usefully do? There are three issues on which Washington should focus: fostering an economic balance of power in Asia that promotes regional stability, achieving more reciprocity in US–China relations and addressing the North Korean nuclear and missile problem.

A central part of Xi Jinping’s geoeconomic vision is the expansion of regional links and the promotion of urbanisation and growth on China’s periphery to make China the central node in this growing region. For Beijing, this means north–south connectivity — namely supply chains that originate in China and extend to the Indian Ocean, South China Sea, Andaman Sea, Bay of Bengal and beyond.

Unless Washington wants Asia to become a unipolar sphere of Chinese influence, it should become more involved in the construction of regional infrastructure to foster linkages that are not just north–south but also east–west from India to Vietnam through Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia and on to Japan and the wider Pacific.

Turning to reciprocity, when China joined the WTO in 2001 its overseas trade and financial involvements grew enormously. So too did its global trade surplus and bilateral trade surplus with the United States. Beijing soon had the technology, capital and capacity to seize the opportunities of openness abroad without providing reciprocal domestic access to the United States and others.

From 2008 onwards, the pace of domestic economic, financial and foreign trade liberalisation slowed. China’s world trade partners came to realise that as China leapt outward to seize opportunities, it did not reciprocally open itself in areas where foreigners enjoyed comparative advantages. Consequently, the issues of ‘reciprocity’ and ‘fairness’ have moved to front and centre in US–China relations. US companies are now asking themselves why Chinese entrepreneurs should be able to freely acquire US service and technology firms when these areas in China are closed to foreigners.

While US feelings of resentment mount, finding ways to enhance reciprocity with Beijing that do not injure US workers or other bystanders is hard. Limiting Chinese investment into US employment-generating firms diminishes US job opportunities. On the other hand, ignoring the problem invites extremist proposals at home as well as contempt in Beijing.

Finally, the issue of North Korea. Trump thought his predecessors had been right in pressing Beijing to put more pressure on North Korea and in their assessment that Beijing had sufficient means to do so. Where they had gone wrong, Trump believed, was in not making it worth Beijing’s while to apply the necessary pressure.

So President Trump suggested that Washington would give Beijing concessions in other areas — trade and Taiwan among them — in exchange for pressure on North Korea. Of all the reasons that this approach has not worked out (including the viability of some of Trump’s promised consessions) the most dominant is that Pyongyang resists following any external advice that it fears would be lethal to the regime.

Consequently, the Trump administration is left with the same stark choices as its predecessors, except that Trump has staked even more on the issue and North Korea is further down its deliverable nuclear weapons path.

It is time for Washington (in close consultation with its South Korean and Japanese allies) to acknowledge that North Korea has a modest nuclear deterrent, and that as a result the United States should shift its aim from denuclearisation to deterring the use and further proliferation of these capabilities.

The US–China relationship is fraught with problems and will be for the foreseeable future. The United States is no longer positioned to compel cooperation from China. Any policy changes from Beijing must be negotiated, and within this negotiation Washington must seek a balance of power and interests.

David M Lampton is Professor and Director of China Studies in the School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. His most recent book is Following the Leader: Ruling China, from Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping.

This article appeared in the most recent edition of East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘China’s Influence’.

Thanks for an interesting analysis. The point about the USA needing to engage in projects aimed at ‘fostering regional infrastructure’ that goes from east to west as well as north to south is well taken. But the author fails to note that President Trump has indicated via his withdrawal from the TPP and the Paris Climate Accord that he has little interest in, let alone the capacity for in my opinion, multilateral diplomacy. Secretary of State Tillerson is more involved in reducing the size and capacity of the State Dept than he is in overseeing and supporting a staff of experienced diplomats who can accomplish such complex and time consuming goals.

I agree that the DPRK is not going to allow President Xi, or anyone else for that matter, to dissuade it from doing what it sees as in its best interests. All it has to do is took to what happened to Libya and Iraq to see what might occur should it give up its nuclear weapons. And President Xi is not going to risk destabilizing the regime with the kinds of economic sanctions, if not covert military action, that would be needed to get the DPRK to stop these efforts. The Washington Post has a story in its 12/10 edition about the need for the USA to accept the fact that N Korea is now a nuclear power. President Trump, however, is far from doing so.

Finding ‘a balance of power and interests’ in the context of these two issues will be a very great challenge to be sure!