Just before the 19th CCP Congress in 2018, the Cyberspace Administration of China released one of the most authoritative policy documents to date outlining Chinese thinking on cyberspace. The document outlines the need to ‘promote the deepened development of military–civilian integration for cybersecurity and informatisation’. It also features instructions to implement civil–military integration systems, cybersecurity projects and innovation policies.

This policy document followed the creation in January 2017 of the Central Commission for Integrated Military and Civilian Development. Under the instructions of the Commission, China’s first ‘cybersecurity innovation centre’ was established in December 2017. Operated by 360 Enterprise Security Group (one of China’s primary cybersecurity companies), the centre’s remit is to foster private sector cooperation to ‘help [the military] win future cyber wars’.

The strong civil–military dimension of Chinese military power has existed since the formation of the People’s Republic of China. Mao’s ‘people’s war’ doctrine stressed that China’s military advantage lay in mobilising the vast Chinese population.

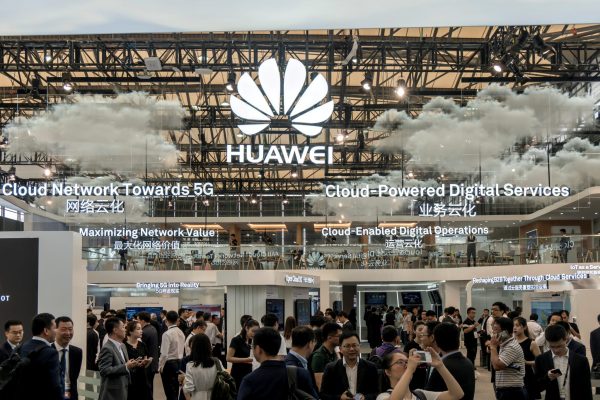

The push to leverage the civilian sector for the development of China’s military cyber capabilities is gaining steam outside of military circles as well. The National Outline for Medium and Long Term Science and Technology Development Planning (2006–20) emphasises the importance of integrating civilian and military scientific and technical efforts. The PLA has heeded such calls, deepening its partnerships with the civilian telecommunications sector — especially ZTE and Huawei — and developing further links with universities.

China’s ‘cyber militias’ are one of the clearest products of this shift. These groups have grown to feature a collective membership of more than 10 million people since the turn of the millennium, and are often based in universities and civilian corporations. While the PLA endorsed cyber militias as a concept in 2006, these groups will likely be restrained to cyber espionage as opposed to offensive cyber operations, given the risk of potentially undermining the work of regular PLA cyber units.

Of the cyber militias, China’s infamous ‘patriotic hackers’ are perhaps the most well known. While these hackers can be a useful tool in hampering state adversaries, they can also often be unruly, erratic and heavy-handed. These hackers are typically driven by popular nationalism, as demonstrated by instances like the cyber stoushes between US and Chinese hackers that followed the US EP-3 incident in 2001.

The Strategic Support Force (SSF) has been the PLA’s answer to mitigating the risk of erratic cyber militias while still harnessing their capabilities. Established in December 2015 to merge and centralise all of the PLA’s space, cyber and ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) capabilities in one body, the SSF has also assumed control over a number of PLA research institutes. The integration of these civilian entities into formalised state structures like the SSF represents a desire by China to mitigate the volatility of these hackers.

But this integration means the PLA and the Chinese state will have to forego plausible deniability when their hackers’ operations are uncovered by other states. The improved US ability to attribute cyber operations to Chinese actors, combined with Washington’s budding approach of sanctioning major Chinese state-owned enterprises in retaliation, has made Beijing realise it needs to run a tighter ship.

The centralisation that Beijing is pursuing is a manifestation of the so-called ‘corporate state’ that increasingly defines the Chinese political system. Here, the CCP acknowledges the presence of societal interest groups as an inevitable result of a pluralising society. At the same time, the CCP seeks to co-opt or direct the behaviour of these entities to serve its ends and maintain stability.

The civil–military dimension of China’s cyber power projection has been sporadically apparent since the early 2000s. But it is only recently that we are seeing concerted efforts to leverage the civilian sphere and, more importantly, to centralise and organise it so that it can consistently serve China’s defence and military aims.

Nicholas Lyall is a researcher at the Strategy and Statecraft in Cyberspace program at the National Security College, The Australian National University.

Funny how the USA is unable or unwillingly to create a cyber-power force both in its government and in the private workforce; yet, the CEOs are importing its computer force overseas and not investing in the American population, and yet, they are complaining about high tech jobs being unfilled and how the schools are not prepared the computer force of the future, not to mention they are not investing in their own workforce.