Labour migration is of critical importance to Southeast Asia. There are an estimated 7 million migrants across ASEAN. Intraregional migration in Southeast Asia has grown by over 10 per cent in the two decades leading up to 2015 even as migration trends in other regions have either held constant or fell. Southeast Asia contains both labour-sending and labour-receiving states. On the receiving end, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand are estimated to receive over 96 per cent of total intraregional migrants. On the sending end, most migrants hail from Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia and Myanmar.

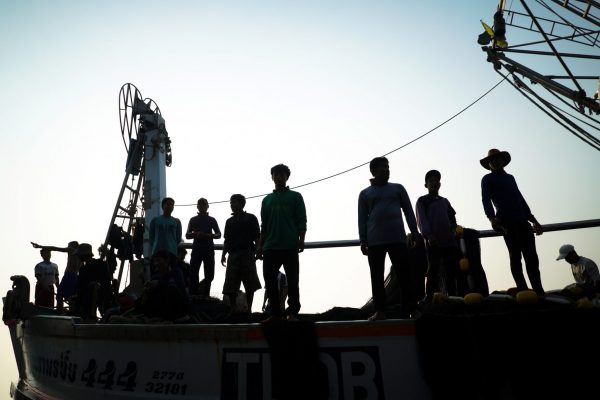

Most intraregional migrants in ASEAN are low-skilled workers, especially those from the developing cluster of ASEAN countries: Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam. These workers often assume roles in the domestic care and construction sectors. The lower-skilled and often less educated nature of these migrants make them especially vulnerable.

Recognising the need to protect migrant rights, ASEAN has pursued various regional measures to combat exploitation. The 2007 Cebu Declaration laid out general principles as well as broad commitments for both sending and receiving states. It also specified several ASEAN commitments, including establishing human resource development programs and pursuing capacity-building practices. While a helpful first step, migrant advocates have expressed concern that regional commitments are often too general and that they are unaccompanied by tangible policy vehicles for implementation.

Paired with ASEAN’s need for consensus-based decision making, the divergence of interests between labour-sending and labour-receiving states often stalls progress. Against this backdrop, the eleventh-hour delivery of the Manila Consensus in November 2017 remains a surprise to some. Consensus was challenging to obtain and required the removal of binding-language, fuelling fears of future non-action. In its final form, the Manila Consensus essentially serves as a renewal of the commitment made in the Cebu Declaration with few substantive changes.

Binding or not, the Consensus is a significant step toward achieving greater protection of migrant rights. The Manila Consensus demonstrates a strong and clear commitment and ensures that the issue of migrant rights remains on the agenda. Beyond reflecting commitment, these regional agreements are particularly crucial in encouraging continued action by non-state actors. Understanding the legacy of the Manila Consensus requires looking beneath the state and paying attention to the actions of stakeholders at the domestic level.

The Manila Consensus’s call for partnerships with domestic actors such as NGOs is critical because governments cannot act alone. Governments are broadly neutral actors who are constrained in regional negotiations by public opinion and domestic legitimation concerns. Seen this way, strong nationalistic sentiments that fuel local opposition to migrant workers pose the biggest challenge to labour mobility and the protection of labour migrants in the region. Regardless of whether these sentiments are fuelled by local economic anxiety or by perceptions of unbridgeable cultural differences, they create an atmosphere of hostility that is then mirrored in government policy posture.

ASEAN’s value proposition is its ability to nudge public opinion and alter domestic legitimation considerations. Is it capable of this? Despite observers’ generally positive public outlook on ASEAN, there is broad agreement that a regional identity remains a goal rather than a reality. While ASEAN may not be able to offer a compelling alternative discourse, it does have the structural ability to empower non-state actors who in turn influence local discourse. Such influence can translate into a more favourable public disposition that allows governments to renew their policy positions.

An issue does not need to persist on government agendas and be at the forefront of public consciousness for action to happen. On the contrary, for a contentious issue with polarising public views, the opposite is true. Diverting public attention toward new and different objectives provides much needed space and flexibility for stakeholders to engage and persuade the public and make the political climate more amenable to future change. The Manila Consensus is an example of how this process can work.

Track-two initiatives like the ASEAN Forum on Migrant Labour allow ASEAN to legitimise and build capacity among non-state actors. Greater legitimisation stems from the ability to claim a higher and broader mandate while capacity building occurs in the exchange of best practices and the building of collaborative networks. This process enables ASEAN to indirectly alter public consciousness and create a friendlier political climate. Over time, these nudges can align domestic legitimation considerations and enable governments to achieve new and greater consensus at the regional level.

At a time when global trust in regionalism is waning, the Manila Consensus represents a timely renewal of ASEAN’s commitment to what the Cebu Declaration began. The existence of an intermediary like the Manila Consensus enables non-state actors to sustain their public influence, which in turn influences the political climate and makes broader mandates possible.

Due to the death of Adelina Lisao, Indonesia is threatening a moratorium on sending domestic workers to Malaysia. Such threats fuel anxiety and hostility and only serve to reinforce protectionist sentiments in the region. This risks unravelling the efforts that ASEAN has made to influence public opinion. It is exactly at these moments of uncertainty that ASEAN should look to leverage its non-state partners to nudge domestic legitimation factors. The Manila Consensus is ASEAN’s next move in the long game. Non-state actors, over to you.

Tommy KS Koh is a Master of Public Policy and Global Affairs Candidate at the University of British Columbia where he is also a Graduate Student Researcher at the Institute of Asian Research.