Over the past two years, the National League for Democracy (NLD) government has struggled to address several policy priorities, including economic liberalisation and the numerous security challenges in the country’s border regions. The civilian government has had to adjust to an uneasy symbiosis with the Myanmar Armed Forces (or Tatmadaw). The Tatmadaw still holds much influence over the government in the form of oversight of over 25 per cent of upper- and lower-house seats in the Parliament as well as key posts such as the Ministry of Defence.

The limits of civilian authority are well illustrated by the crisis in Myanmar’s north-western Rakhine State, which has seen a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees into neighbouring Bangladesh since August 2017. The Rakhine crisis has had a negative effect on Myanmar’s attempts to ‘come in from the cold’ after a long period of diplomatic seclusion under the previous military junta. The possibility of the country slipping back into isolation cannot be discounted.

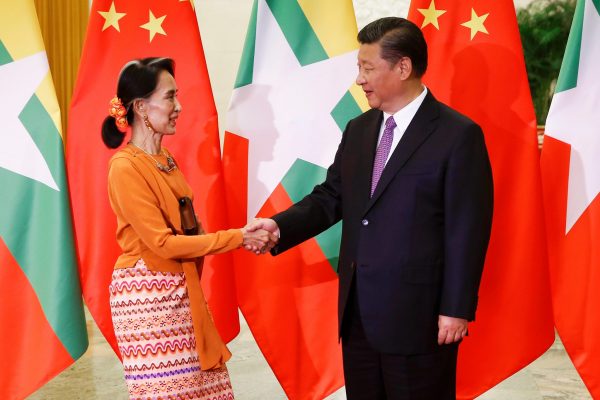

Beijing was one of Myanmar’s few regional friends during the country’s period of military rule. But divisions appeared as Myanmar began to move towards political reform under former president Thein Sein. This was illustrated by the Thein Sein government’s suspension in 2011 of the China-backed Myitsone Dam project due to local opposition and frictions caused by cross-border smuggling of goods including jade and lumber. Yet in June 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping met with then-opposition leader Aung San Suu Ky — a strong indicator that Beijing was open to the possibility of democratic reform in Myanmar and was willing to build relations with an NLD-backed government.

After the current Myanmar government took office, the country’s economic relations with China remained strong, with bilateral trade figures estimated at US$10.8 billion for the 2016–17 fiscal year. Beijing views Myanmar as an essential component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), given Myanmar’s resource endowments and its location on the Indian Ocean. A key component of the BRI has been an ambitious deep-sea port project in Kyaukpyu on the Bay of Bengal, in which China assumed a 70 per cent stake in October 2017.

BRI projects in Myanmar, in addition to initiatives and economic diplomacy in other areas of the Indian Ocean, have raised concerns about strategic encirclement with Myanmar’s other big-state neighbour: India. China has been courting the Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and opened its first overseas military installation in Djibouti in 2017. Over the past two years, Beijing has sought to soften the impression that its Myanmar diplomacy is largely based on resource interests and geo-economics. A November 2017 meeting between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Aung San Suu Kyi saw a proposal for an ‘economic corridor’ between Myanmar and the neighbouring Chinese province of Yunnan to enhance Myanmar’s development.

Any development in this area will be contingent upon stabilising the border region, which is still subject to violence by ethnic militias including the Kachin Independence Army. Other groups, such as the United Wa State Army (UWSA), have tentatively accepted a cease-fire with the central government. China has pledged its support for a comprehensive peace deal in the wake of concerns about smuggling, the drug trade and refugee flows into China. It is also concerned about the potentially adverse effects on cross-border trade and joint infrastructure projects, such as the Myitsone Dam. Several of the ethnic militias, including the UWSA, have stressed that China’s ongoing involvement in the peace process is essential to the success of the talks.

While Beijing has largely sought to remain neutral on the Rohingya situation, in October 2017 the Xi government offered a ‘three-phase’ solution to the Rakhine crisis. The phases would be: a cease-fire to prevent further refugee flows followed by the establishment of a stable line of communication between Bangladesh and Myanmar to jointly tackle the crisis and lastly a long-term solution to acknowledge widespread poverty in Rakhine as a factor in the humanitarian emergency. But an end to the crisis remains elusive despite ongoing international pressure. While China wishes to be seen as a responsible great power in encouraging an end to the crisis, the country is also concerned about the future of the Kyaukpyu project, which is based in Rakhine and is considered an essential component of the BRI.

The stage appeared to be set in 2016 for a diversification in Myanmar’s foreign policy, given initial enthusiasm in East Asia and the West for building new ties with the Aung San Suu Kyi administration. But the events in Rakhine State have greatly slowed this process. The United States re-introduced select sanctions on Myanmar in December 2017, and the country appears to be a low priority for the US government. Beijing appears to remain in a dominant position as it applies to Myanmar’s foreign policy, a relationship poised to affect future Western diplomacy and strategy in Southeast Asia.

Marc Lanteigne is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies, Massey University.