Not even a year ago, the world’s two most populous countries locked horns in a face-off at Doklam. But the dragon and the elephant seem to have agreed to settle their differences and dance to the tune of rising global uncertainties, at least for now.

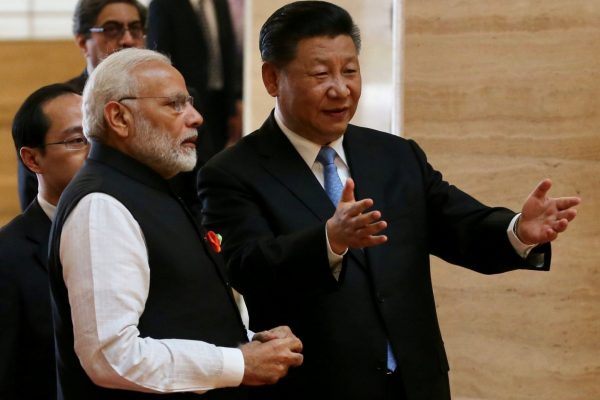

For an informal summit, the Wuhan meeting appeared to cover a wide range of issues. No agreement was signed and no joint statement was issued, but both leaders emphasised their determination and commitment to a future characterised by positive bilateral ties. Modi and Xi reportedly held multiple one-on-one discussions with only their interpreters present. Media from both countries are hailing the talks as open, cordial and warm. The headline ‘2 days, 7 events, 9 hours’ says it all.

The major focus of the meeting was border peace — an obvious focus given the impact of last year’s 73-day-long stand-off on an already sour relationship. The confrontation highlighted how a dangerous tug-of-war between the two nuclear powers could easily escalate into a military skirmish. It also revealed that a Cold War zero-sum mentality towards conflict is still present. Both leaders have agreed to ‘issue strategic guidance to their militaries to strengthen communication’. To do so, Chinese and Indian militaries will soon set up a hotline between their headquarters.

Another major outcome of the summit came in the form of expressions of interest in undertaking a joint economic project in war-torn Afghanistan. Details are still in the works, with some concerned that such a move could rile Pakistan, which feverishly refuses to recognise India’s growing role in the country. This also means that the regional geopolitical equation could shift depending on how the India–China–Pakistan triangle realigns.

Other thorny issues such as India’s trade deficit, terrorism, the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the Belt and Road Initiative were also discussed. Both leaders vowed to collaborate on tackling global challenges including rising protectionism, climate change, food security and sustainable development. Overall, the meeting was both significant and informal enough to win the hearts of those in both countries.

It is India that has a bigger stake in a friendly relationship. For China, the meeting — which came at the request of India — was an opportune occasion to display its charm offensive against a backdrop of increasing and intensifying friction with the United States. Modi, who is looking ahead to next year’s election, has more to lose — he desperately needs a quiet border, even if that means sleeping with the enemy.

The invincible leader of India is looking less invincible as the end of his first term approaches. His political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), still dominates Indian politics. It recently became the largest political party in the upper house after the biennial election in March 2018. But discontent is rising over unemployment, low wages, farm distress and slow growth. Modi’s reticent response to two rape cases that rocked the country has also left stains on his path to a second term.

Modi’s hug diplomacy and showmanship indeed attract international attention, but his charm is not delivering. The United States is intensifying its trade offensive at India’s expense, despite deepening ties in recent years. India’s ‘neighbourhood first’ approach to foreign policy is also in the doldrums. Chinese flags are being raised on India’s doorstep in Sri Lanka, Nepal, the Maldives and perhaps Bhutan at a rate of knots.

Modi’s young, urban supporters are turning their back and his political allies are leaving the coalition. The BJP is likely to win the next general election, but the political circle in Delhi now cautiously predicts that Modi’s second term is less likely. Amid such political uncertainty, Modi simply cannot afford another flare-up with China.

The more important question is whether a renewed mode of operation between the two countries will last beyond Wuhan. Obviously, one meeting cannot fix deep-rooted problems. This is not the first time that the two leaders have sought to set new milestones in bilateral relations. Modi and Xi have already exchanged kisses of reconciliation and hinted at the possibility of a strategic alliance when each visited the other’s hometown in 2014 and 2015. Last month’s informal meeting was ambitious and bold, but it was not historic.

If history is to be of any guidance, it becomes easy to see the relationship returning to old days of darkness. As Kissinger once said: ‘there are no permanent friends or enemies, only interests’. This is the single most important lesson India should keep in mind if it wants to keep its ‘frenemy’ in check.

Soyen Park is an independent researcher based in Delhi.