While this shift is a welcome change, unless the developments leading up to this point are properly understood Japan may find itself unable to respond appropriately if history repeats itself and bilateral relations takes another turn for the worse.

Japan–China relations had deteriorated since September 2012 when fierce anti-Japan demonstrations took place in China as debate raged in Japan over the nationalisation of Okinawa Prefecture’s Senkaku Islands.

In December 2012 the Democratic Party of Japan administration was replaced by a Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) cabinet, but this has not led to any significant changes in Japan’s relations with China. From the Japanese perspective, China unilaterally set out to improve relations with Japan and has now proclaimed these relations to be back on their normal course.

The backdrop to the anti-Japan demonstrations in China was a domestic political struggle over the change of leadership as the Hu Jintao presidency drew to a close. That Premier Li was recently able to make an official visit to Japan demonstrates that the adverse impacts of this domestic political struggle on Japan–China relations have for the most part been erased.

Prior to the November 2012 Chinese Communist Party National Congress, which saw the elevation of Xi Jinping to the top party position of general secretary, the Hu administration was under attack by interests friendly to former president Jiang Zemin. Jiang’s supporters ganged up on the Hu administration and rebuked it for showing weakness to Japan. The history between the two countries readily turns China’s Japan policy into a tool for political infighting. An example of the effect of this political infighting was China’s withdrawal from a 2008 agreement on joint development of gas fields in the East China Sea, which was reached by the Japanese and Chinese governments after considerable effort.

Current President Xi Jinping’s efforts to solidify his power base has had a positive impact on relations with Japan. Engaging in an aggressive ‘anti-corruption campaign’, Xi has managed to sweep away most of his political rivals connected with his predecessors Jiang and Hu. Political infighting has been settled, for the moment at least, under a system of one-man rule by Xi. It is perhaps somewhat ironic that the authoritarianism in China that allowed a constitutional amendment to lift presidential term limits has led to the current stability in China’s relations with Japan.

The international circumstances surrounding China are also developing to the advantage of Japan–China relations. China’s relations with the United States are unstable both politically and economically and the US–North Korea summit could open the way to major historical changes on the Korean Peninsula. As China’s priorities are to secure its interests on the Korean Peninsula and mend its relations with the United States, it cannot afford to quarrel with Japan.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also enjoys the advantage of being able to communicate frequently with US President Donald Trump, and China believes that it would be in its own best interests to establish relations allowing it to also keep in regular contact with Abe.

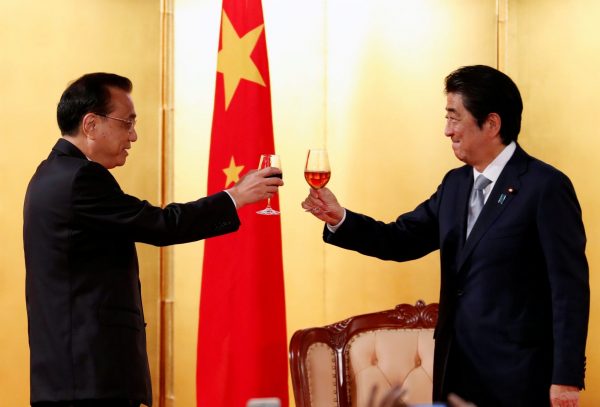

Abe is in a difficult position due to domestic political issues in Japan and will face a tough challenge in the September LDP leadership election, but Li still invited him to visit China in the future. Xi will be making his first official visit to Japan in June 2019 to attend the Osaka G20 summit, and there is every possibility that mutual visits by the leaders of Japan and China will be fully restored.

Li’s extended visit to Japan lasted four days and three nights, one day longer than initially planned, and he spent the final day from the morning onwards together with Abe in Hokkaido in a surprising show of bonding. Li did not delve into issues such as the Senkaku Islands dispute during his visit. He even expressed a degree of understanding and support for Japan’s stance vis-a-vis North Korea on resolving the abduction issue.

The two leaders also agreed to launch the ‘Japan–China Maritime and Air Communication Mechanism’ that is designed to avoid unexpected clashes in the air or at sea. The provisions concerning the area around the Senkaku Islands remain vague though, and this could become a source of tension in the future.

Japan should pursue cooperation with China in the economic sphere where it serves Japan’s national interests, and it should adopt a forward-looking attitude on the business cooperation that third parties have agreed to extend to China under the Belt and Road Initiative. For its part, China recognises that overzealous competition to offer the cheapest bids for overseas infrastructure improvement projects is pointless.

The intense international calculations over the Korean Peninsula, US–China relations and Taiwan will likely continue for some time. Japan needs to strategically examine its relations with China with a proper understanding of the complex power dynamics involved.

Katsuji Nakazawa is Editorial Committee Member and Editorial Writer for Nihon Keizai Shimbun (Nikkei).

This article was first published here in AJISS-Commentary.

Thanks for an informative analysis. I had not known of the manner in which China’s internal domestic political dynamics with the transition from Hu Jintao to Xi Jinping had been a factor in the relations between the two countries. As noted here the issue of the Senkaku Islands remains unresolved and potentially problematic.

Not noted here is the ways in which Abe/Japan policies and behavior have contributed to the tensions that have affected relations since 2012. Surely, the tensions between the two countries are not just due to China’s own internal power struggles?

It will interesting, as well as important, to see how this evolves, assuming of course that Abe remains the leader of the LDP after September.