the Communist Party’s leadership has the unswerving support of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and other security forces; these forces are enthusiastic about the Communist Party and enjoy a privileged position in the state and society; and both the Communist Party and the PLA have the unwavering support of the patriotic Chinese people, who will take umbrage at any perceived affront to China.

But this manufactured image has always been problematic. For example, one political scientist spent over a year interviewing policemen, who, like cops nearly everywhere, kvetched about poor pay, low status, and a lack of operational autonomy and opportunities for advancement. Many citizens see Chinese police forces as lazy and corrupt.

Studies on Chinese constitutionalism in the early 1950s found policemen worried that better educated citizens would give them guff by citing their constitutional rights during arrests. They also fretted about their marriage prospects because of their paltry salaries and low ‘cultural level’ and hoped that spiffy new uniforms would improve their chances. In Shanghai, some former PLA soldiers turned police officers were called ‘PLA trash’. PLA soldiers who returned from US or UN captivity after the Korean War were treated particularly poorly.

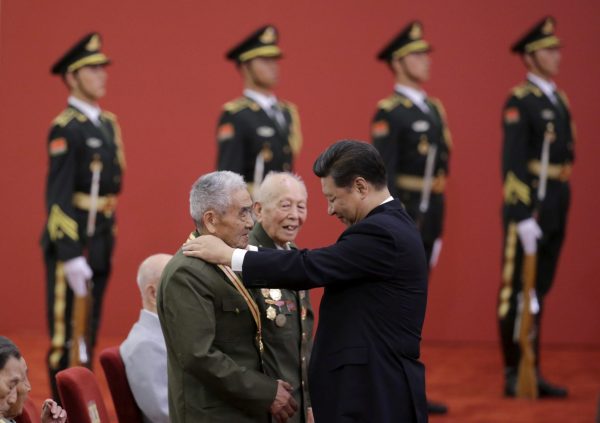

Not much has changed over 60 years. PLA veterans have been lauded in the official media as liberators, builders of socialism, protectors of the nation and heroes worthy of emulation. But the veterans themselves have complained to anyone in earshot and in messages posted to the ‘Voice of the Veteran’ and other websites about widespread discrimination in employment, physical abuse at the hands of the police, lack of social respect, difficulty finding wives, ungrateful bureaucrats and meagre to non-existent benefits. The veterans protested mistreatment as early as 1951 and they continued after the Korean War and during the Cultural Revolution.

After former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping downsized the PLA in the early 1980s in the wake of China’s short border war with Vietnam, veterans found themselves unprepared for the new market economy, which valued money and education far more than military or policing skills. Rural women, always practical, preferred to marry wealthy farmers now that getting rich was just as ‘glorious’ as fighting a war.

For some ex-soldiers, securing a position in the security forces was a step up. Compared to the labour market it was relatively secure and offered benefits. But for the majority, military service did little to improve their prospects. Upon discharge they were sent home to resume farming. Many officers found themselves without stable employment once the factory positions that they had been assigned evaporated when firms went bankrupt or changed ownership.

Today, the ranks of protesters in China are filled with hundreds of thousands of these former soldiers and officers. Among them are the veterans of China’s war against Vietnam, many of whom now live in poverty in inland provinces, and low-to-mid level officers who were ‘downsized’ by China’s changing economy. In an interesting twist, facing them across the police barricades are cops — some of them former soldiers themselves — who otherwise share the protesters’ social class, life experiences and challenges.

This veteran-on-veteran antagonism is useful to the government (and is actively encouraged by it) because it prevents current and former servicemen from uniting based on their shared interests.

Standing mostly on the outside of all of this frustration and conflict, literally and figuratively, has been the PLA. Many veterans go to Beijing to protest outside of the PLA’s General Political Department or the offices of the Central Military Commission, where they call upon the brass to run interference on their behalf with civilian authorities in the provinces who fail to implement national policies. But such pleas are more symptomatic of veterans’ desperation than of the PLA’s clout.

In China’s highly decentralised fiscal system, former soldiers are not under the jurisdiction of the PLA but rather of the administrative authorities in the region from which they were drafted. Many of these happen to be in rural areas and small towns that lack resources to help them. Making matters worse, these local officials are penalised by the higher authorities should returned veterans file petitions in Beijing.

Abuse at the hands of local officials — who operate without much concern for state ideology or legitimacy — or at the hands of the thugs they regularly hire, is a common cause of protest. Veterans can also suffer when they are forced back home and officials take their revenge.

The Chinese public is largely disinterested in all of this back and forth. There is virtually no social mobilisation on behalf of former soldiers (online or off), in contrast to other cases of social injustice. It is far from clear that the public sees them as worthy of their sympathy or support. What, in the end, did veterans contribute to China’s prosperity and security in the last 40 years of peace? Didn’t many of them have cushy jobs in factories for decades?

It is then hardly surprising that the PLA has difficulty recruiting young people who have other opportunities by virtue of education, connections or wealth. Further hampering recruitment is growing knowledge of the insecurity facing soldiers when they become veterans. The government has improved policies towards veterans in recent years, but this is unlikely to be a panacea: the decentralised funding and implementation mechanisms remain unchanged, local officials still fear their activism and veterans cannot form national-level organisations to lobby on their own behalf (unlike their counterparts in most countries that experienced large-scale warfare).

China’s image makers work overtime to convince people that veterans, policemen and others in the security apparatus are worthy of respect and honour. But the historical legacy of discrimination against military personnel, the long peace and rampant materialism make this a near-impossible lift.

Neil J Diamant is Professor of Asian Law and Society at Dickinson College.

In the USA, the upper ranks of the American NCOs and officers are cashing in their military experience in order to get a career in the arms industries with six-figure salaries or having consultant jobs in the corporate media while not caring about people under their command, the homeless veterans or the country overall.

With a bloated Defense Budget to benefit the all-pervasive Military-Industrial-Complex the United States has been engaged in endless wars in four continents, involving the deployment of millions of troops, in the last 40 years.

It is therefore amazing that an American academic would have the nerve to criticize the plight of the security personal in another country when a report, released in February of 2014 by the Department of Veterans Affairs, showed that 22 American veterans committed suicide every day.

This meant that approximately 8,030 veterans tragically killed themselves every year. That was more than the total number of US troops killed in the Iraq war.

A 2015 Washington Post & Kaiser Family Foundation poll showed that in the United States “more than half of the 2.6 million veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars struggled with physical and mental health problems stemming from their service.”

Of those who took their own lives, more than 5,540 were 50 or older as they saw a bleak future ahead as their health care entitlement lasted only for 5 years after the end of service.

That prompted some veterans’ advocates to remark ruefully that “it’s easier for older veterans to feel America has forgotten their sacrifices.”

Although two Veteran bills were introduced in the Senate in 2014 to include a provision to extend enrollment eligibility for VA health care for more than five years after the end of service that only applied to Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans but excluded the Vietnam war veterans, 30per cent of whom suffered post-traumatic-stress disorders, compared with 11 to 20 per cent of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the report said.

This prompted Tom Berger, executive director of the Vietnam Veterans of America National Health Council to lament: “You know, ‘We’re just old guys, and we’re going to die, so why pay much attention to them?’ That’s the kind of the feeling that some of our members have.”

It’s sad that the US with such a ridiculous Defense/Security budget of nearly US$1 trillion today, which is more that the Defense Budgets of the next 10 major countries combined, should treat their war veterans, many of whom are ill, jobless and homeless, with such appalling disrespect.

China does not allow independent reporting, but takes liberties quoting free flowing information in democracies. Because unlike the civility of democracies, dictatorships can control information and news. China needs to mature and reciprocate courtesies that it has till date abused. But under a dictatorship, such information lacks credibility. As the proverb goes, ‘Lies, damned lies & statistics’. From China, it is only statistics.

As the author has said in earlier comments – ‘Three things cannot hide for long – the Sun, the Moon and the Truth’. I am sure that there is enough dirt in China and its leadership, which will come out in due course.

1 Yes, according to Buddha, “Three things cannot be long hidden: the Sun, the Moon and the Truth’.

So is India a democracy or a demoncrazy then? The readers can decide.

1) Deepa Narayan wrote in the Guardian: “India’s abuse of women is the biggest human rights violation on Earth” Tragic rape cases have shocked the country. But the everyday suffering of 650 million Indian women and girls goes unnoticed

“According to the National Crimes Records Bureau, in 2016 the rape of minor girls increased by 82% compared with the previous year. Chillingly, across all rape cases, 95% of rapists were not strangers but family, friends and neighbours.”

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/27/india-abuse-women-human-rights-rape-girls

2)In April this year “Eight dead in massive India caste protests”.

The “Dalits are some of the country’s most downtrodden citizens because of an unforgiving Hindu caste hierarchy that condemns them to the bottom of the heap.”

“Despite the laws to protect them, discrimination remains a daily reality for the Dalit population, thought to number around 200 million.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-43616242

3)India lynchings: “WhatsApp sets new rules after mob killings”.

“These changes come in the wake of a series of mob lynchings that have seen at least 18 people killed across India since April 2018. Media reports put the number of dead higher.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-44897714

2 Indian proverb: “Those who live in a glass-house should hide in the cellar”.

Thank you for validating what I have stated – China censors all its news and parades the negativities of a democracies. I am debating about the government in China and its armed forces – not the citizens or law and order situation with the citizens, which is closed to independent reporting by the Chinese government.

Google, Facebook & Twitter are banned in China, the highest censorship globally.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/06/technology/china-generation-blocked-internet.html

We can debate when independent reporting is instituted in China. And hopefully, democracy.

WRT the Indian armed forces, the pensions are fully in force. And an agitation is on for increasing the same to institute fairness – the democratic way.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/ht-explains-what-is-orop-and-why-are-veterans-still-unhappy/story-bmzyIKZ46jdNG95GnRn2cK.html

Perhaps the Chinese soldiers would be happier and better off serving in the Indian army – or for that matter, any army with a democratic government.

To get an insight into the situation, the below two links bring out the contrast

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-43588435

https://nypost.com/2017/09/29/chinese-muslims-ordered-to-turn-in-korans-and-prayer-mats-in-extremist-crackdown/

The link below brought Hilters concentration camps for Jews to my mind:

https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2159521/china-rejects-un-panels-allegations-one-million-uygurs

Even Hitler did not ban the holy texts for the various faiths, but China has confiscated the Holy Quran to banish Islam.

Can these links be published in Chinas chat, app & media like the Global Times?