First, it serves as a reminder that China takes the international system seriously. It seeks to influence it from within by promoting Chinese representation in key international bodies.

Beijing joined the international system with its recognition by the UN in 1971, and China is now the third largest funder of United Nations activities though its nationals are still very much under-represented in UN bodies.

Although China was one of the founding members of the IMF, the People’s Republic only assumed responsibilities for Chinese membership in April 1980.

China’s accession to the WTO was approved by the United States and other members in December 2001, after 15 years of arduous negotiation.

China is committed to participation in the established international order, though it is dissatisfied with aspects of that order, and the hierarchy of the states within it. It also espouses principles and accepts the rules through which they are applied consistently with the system’s core objectives. It’s difficult to argue that China is a revisionist power but it certainly seeks to have more say on rules and norms in the evolving international order, including in standing firmly against changing established rules that serve its national interests — most prominently today those of the WTO.

It was not until the early 2000s that Chinese representatives began to assume any positions of importance within the global economic governance system established after the Second World War and a Chinese citizen is yet to serve in a top role at any of those institutions.

In the Bretton Woods economic system, Chinese nationals Shengman Zhang and Justin Yifu Lin were, respectively, managing director (2001–2005) and chief economist (2008–2012) at the World Bank, and at the IMF a Chinese representative has held the position of deputy managing director since 2011. Within the economic sphere, Liu Zhenmin in 2017 replaced Wu Hongbo as Under-Secretary-General for the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, and in 2013 Yi Xiaozhun became Deputy Director-General at the WTO.

The reform of the Bretton Woods economic system is still a work in progress, with Asian quotas at the IMF increased ten years after the global financial crisis but still substantially underweight.

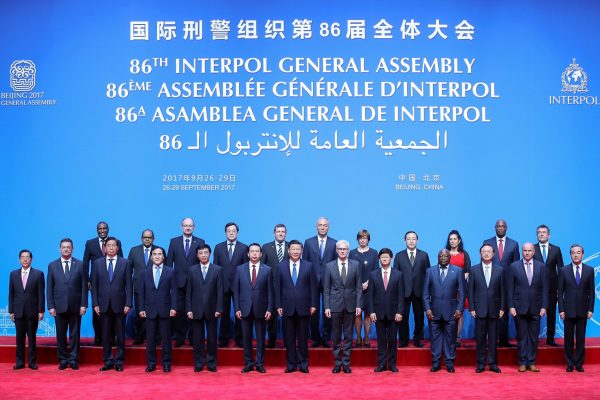

In other spheres, from health, where Chinese representative Margaret Chan headed the World Health Organization from 2007 to 2017, to technology, with Houlin Zhao as current Secretary-General at the International Telecommunications Union, to sports, where Zhang Jilong was the acting president of the Asian Football Confederation from 2011 to 2013, Beijing’s influence within the international bodies has steadily expanded.

Second, the Meng affair illustrates sharply how domestic political imperatives chafe against China’s international responsibilities and diplomacy. Rightly or wrongly, it provides another data point for those who are not comfortable with the idea of an increasingly China-led international order.

Much of the international media concluded that Meng’s detention has harmed China’s global standing. But China’s global standing is hardly likely to be dented by that affair. As an emergent power, China’s global standing hangs more decisively on how it exercises its economic and growing political–military power within the international community.

A key dividing line in competing narratives about China’s rise lies between those who take the domestic character of the Chinese state as a proxy for how China will behave in international affairs and those who do not. For proponents of this view, the arbitrary detention of Meng, as well as issues like the treatment of Uyghurs, internet controls, and the crack-down on freedoms of expression, for example, are the reasons for a morally-based critique of an increasingly Chinese-led international order. But for those who don’t, there is no straight line between domestic and international behaviour.

The connections been the principles that China accepts in the management of the international order and those that govern the Chinese state have been evolving rapidly since the commitment to opening up 40 years ago. In commodity markets and the way in which they work, the connections are tight. In legal and political affairs the gaps are huge and will never close completely — that is the nature of sovereign states. The segmentation of the domestic system from the international system is a question that needs sensibly to be tested in every sphere and will differ in each area, some of which are of more consequence to the international community, and some much less.

The important question, therefore, is whether Xi’s long game — enormous investments in global infrastructure and institutions, which have been vigorously criticised at home for lacking an immediate economic rationale, for example — involves sustained commitment to the current international system or whether it involves plans to upend the current order. There is evidence that could point in both directions.

In this week’s lead essay, Neil Thomas argues that China is heavily invested in the current international system and depends greatly on it for its continued growth on a peaceful external environment. Thomas does not see world domination as a priority for China, or accept that China is a revisionist power, except in the narrow sense that it seeks to reshape international rules to better accommodate its own interests. Thomas might be right, but it’s necessary to drill down deeply and constantly into Xi’s speeches and CCP analysis of ‘peaceful development’, as he has done, to ground that argument in an operational hypothesis. The argument rests on the assumption that China is unwilling to sacrifice peace and stability in pursuit of longer-term goals. Xi Jinping has shown himself willing to make such calculations in domestic politics.

In international politics, how China engages with the rest of the global community and how the rest of the global community engages with China in handling its increasingly fractious relationship with the United States may prove a critical test.

Xi has firmly staked his and the Party’s legitimacy on his vision for China’s great rejuvenation — popularly known as the ‘Chinese Dream’. An international challenge to his domestic political authority, triggered by the economic effects of the confrontation over trade with the United States, could have unpredictable consequences for China’s international calculations if Thomas’s assumption were ill-founded.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.