But how significant is this cooperation between the second and third biggest economies in the world? Is their difficult relationship sustainably on the mend against the backdrop of increasing US–China tensions?

The visit marks an amazing turnaround from the tensions between the two countries earlier this decade. China–Japan ties nosedived in September 2010 in the wake of an incident between the Japan Coast Guard and a Chinese fishing trawler near the Senkaku Islands — claimed as the Diaoyu Islands by China. Ties turned frostier in September 2012 after Japan nationalised three of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, a move that then prime minister Yoshihiko Noda was forced into after the manoeuvring of former Tokyo governor and ultra-nationalist Shintaro Ishihara. Ishihara solicited donations and threatened to buy the islands from their private Japanese landowner, build a port and station Japanese officials there in a move designed to undermine the tacit agreement between Japan and China to maintain a low-key approach to resolving the issue. China responded by suspending high-level political exchanges and large-scale anti-Japan protests in China added to the tensions. Bilateral relations took a further hit in December 2013 when Prime Minister Abe visited Yasukuni Shrine — the shrine which is the place of repose for the souls of Japan’s war dead, including, since 1978, 14 class-A war criminals.

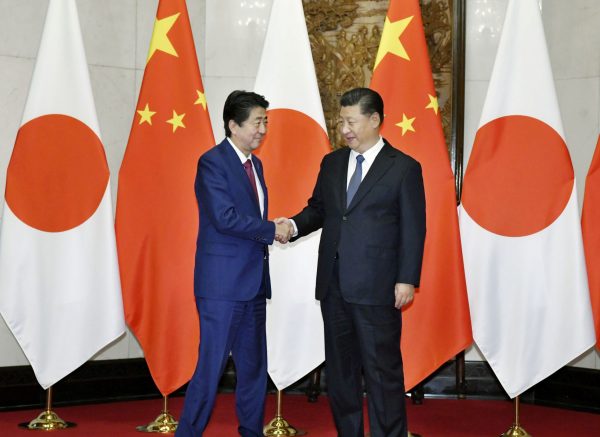

When Beijing hosted APEC in November 2014, Xi and Abe shared an awkward handshake — beginning a gradual process of thawing out the relationship. The second half of 2017 saw relations start to improve further. In May 2018 Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Japan for the China–Japan–ROK trilateral summit as well as a bilateral visit with Abe. This visit saw the announcement of the Maritime and Aerial Communication Mechanism (MACM) to prevent accidental clashes between Chinese and Japanese military vessels at sea and set in train negotiations for the agreements reached in Beijing last week.

In the security sphere, China and Japan agreed to cooperate on maritime search and rescue operations and to resume People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) fleet visits for the first time since 2011. Both sides also reaffirmed their determination to set up a military hotline and begin holding an annual meeting between top defence officials as provided for under the MACM. The head of the Joint Staff of the Japan Self-Defense Forces is also scheduled to visit China next year for the first time in 11 years.

On the economic front, China and Japan agreed to renew a currency swap agreement initiated during the global financial crisis and which expired during tensions in 2013, with a ceiling of 3 trillion yen (US$27 billion), ten times more than the previous agreement. The two countries also agreed to establish a new framework for talks on technological cooperation and intellectual property protection. That is an area of contention with US businesses and in Washington. China also signalled it would lift bans on food imports from a number of Japanese prefectures which have been in place since the 2011 Fukushima earthquake and accompanying nuclear disaster. Abe declared his intent to pursue the early realisation of an agreement on joint development of gas fields in the East China Sea, the negotiations of which were suspended in 2010 after the Senkaku/Diaoyu kerfuffles. Significantly, China and Japan agreed to cooperate on 50 joint infrastructure projects, including projects under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

As Shiro Armstrong explains in our lead essay this week, it is the area of infrastructure that is likely to be the most consequential aspect of the revived China–Japan cooperation for the promotion of regional stability and prosperity. As he puts it, ‘For Japan it’s a pragmatic way to engage China. As Chinese policymakers search for ways to better deploy the country’s vast sums of capital abroad, Japan has experience of doing just that dating back to the 1970s — including of geopolitical pushback. Understanding that the Belt and Road is here to stay, Japanese engagement can shape the massive investments’.

In Armstrong’s review of the visit, he suggests that joint infrastructure cooperation initiatives signal a major shift in China’s approach to the Belt and Road.

Given the vast amounts of infrastructure investment needed around the region to realise growth potential, cooperative leadership from Asia’s two biggest economies will go a long way to ensuring investment capital is utilised efficiently. Armstrong writes that ‘Regional cooperation can help with building consensus around principles for investors and recipients, capacity to assess projects, capacity to put together tenders and with mediation between parties in the event of failed projects’ and that ‘Measures to diversify project and political risk by forming consortiums — just as China and Japan have announced — are a pathway to be encouraged’.

Despite the promise this agenda for cooperation holds, there is still much hard work to do. Territorial and historical issues hang ominously over the Japan–China relationship. Abe’s determination to revise the Article 9 peace clause of the Japanese Constitution and China’s likely negative reaction to a development such as that is also a risk factor which could derail cooperation. In order to move the relationship beyond tactical detente, Japanese and Chinese leaders will need to continue to consistently and clearly articulate shared interests for mutual cooperation, ‘persuading domestic audiences that cooperation is the key to a better future for both countries’. Xi’s planned visit to Japan next year should give momentum to this imperative in the near term.

Hardening US attitudes toward China present a serious obstacle. As Rumi Aoyama explains, ‘There seems to be broad consensus in Washington that the long-standing US engagement policy towards China has failed’, remarking further that ‘On 4 October 2018, US Vice President Mike Pence delivered a de facto declaration of cold war against China in his speech at the Hudson Institute, decrying China’s “predatory” trade, “coercion” and military “aggression”’ and ‘How the United States responds to the thawing of Japan–China relations will indubitably shape the future discourse of Japanese foreign policy’.

The revitalisation of Japan–China cooperation is most welcome in the region as it brings a measure of stability and certainty in dealings between two of the three largest economies, just as the largest is in a crisis trying to make itself great again in ways that appear misguided to its Asian partners and allies.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.