As Western governments imposed sanctions against the junta in the aftermath of the coup, Thailand resurrected its centuries-old bamboo diplomacy to guarantee the regime’s survival. When ties with the United States and Europe became strained, the junta strengthened both its political and economic relations with ASEAN states and China. Clearly Thailand is trying to diversify its foreign policy options.

In particular, the country has been keen to amend its ties with two former enemies in the neighbourhood: Myanmar and Cambodia. Myanmar has traditionally been Thailand’s adversary due to the former’s sacking of the old kingdom of Ayutthaya. Cambodia has also been classified as a national enemy of Thailand. Mutual inimical feelings were exacerbated over the past decade by the territorial dispute over the Preah Vihear Temple, which led to deadly skirmishes along the two countries’ border.

But Thailand shifted its diplomatic stance, adopting an amicable attitude towards both traditional enemies. Bilateral visits have become more frequent. Myanmar’s Army Chief Min Aung Hlaing visited Thailand shortly after the coup to praise the Thai junta for ‘doing the right thing’. Meanwhile, Prayuth and the Cambodian Prime Minister were seen hugging each other, symbolising a step towards improvements in bilateral relations.

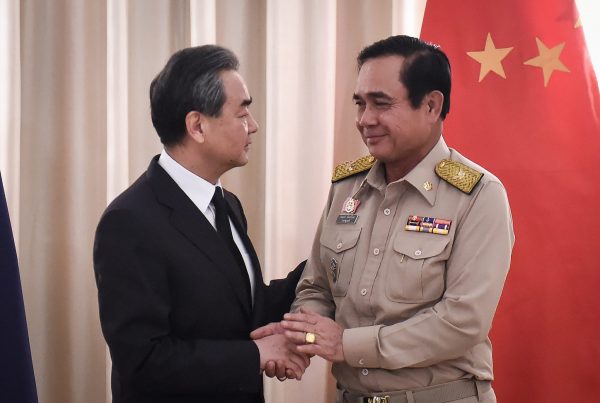

Outside of ASEAN, China has piggybacked the Thai junta by providing legitimacy to the military government. Chinese President Xi Jinping met Prayuth in Beijing in December 2014, a meeting which saw the renewal of a currency swap agreement worth US$11.25 billion. Shortly after, Prayuth welcomed Chinese Premier Li Keqiang in Bangkok, who has become the most high-profile foreign leader to visit Thailand since the coup.

In the face of Western sanctions, Thailand has fallen deeper into China’s orbit in a relationship underpinned by mutual political and business interests. China has no apparent intentions of interfering in Thai politics. Making money, not enemies, has become China’s foremost foreign policy agenda vis-a-vis Thailand. China has showed its willingness to invest in a multi-million-dollar high-speed train project. The newfound friendship has also generated a massive flow of Chinese tourists to Thailand.

China’s assertive foreign policy has compelled Western nations to amend their positions towards Thailand for fear of losing their footholds in the country. US President Donald Trump, despite existing US sanctions against Thailand, rolled out a red carpet to welcome Prayuth to the White House in October 2017. The United Kingdom and France followed in the United States’ footsteps by inviting Prayuth to their respective nations, mostly for trade talks, in June 2018.

Prayuth claimed to the Thai public that his military regime was fully recognised by the world’s superpowers, adding to the junta’s sense of confidence that it can hold on to power. Elections have been postponed countless times. Although the junta has announced that the next election will be held in February 2019, public trust in the government has drastically declined.

Can Thailand’s bamboo diplomacy be celebrated as an effective foreign policy strategy? On the surface, it seems that Thailand has been able to exploit its relationship with China to offset Western sanctions. Reconciliation with the West was also perceived as a success of Thailand’s pro-China policy, which called in turn for more commensurate relations with the Western world.

But economic interests alone are hardly sufficient to warrant long-term support for Thailand’s junta from both China and Western nations. Immediate business profits motivated the West to shift its policies towards Thailand. But this shift hinges on real political change in the country too. The longer the junta is in power, the less confident Western powers will be as they engage in business in Thailand.

For China, the reality is that Thailand is not its only business destination in Southeast Asia. While firming up its influence in Thailand is important, China can afford to take its relations with the junta for granted due to the latter’s overwhelming dependency on Chinese political support. This explains why, for example, the Chinese investment plan in the Thai high-speed train never took off.

Appeasement in foreign relations signifies an unequal relationship. While bamboo diplomacy worked well in the past, Thailand’s domestic politics has served to complicate its foreign policy. Not only has Thailand assumed a subordinate status to foreign powers in order to attain their political recognition, it has ceded control over its business activities with those foreign partners.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is Associate Professor at Kyoto University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies.