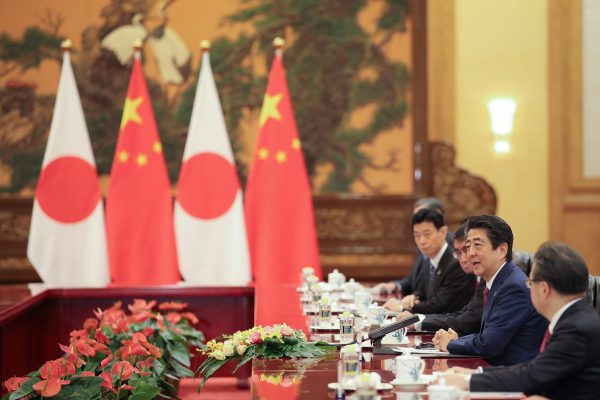

As first steps towards achieving these principles, both governments together signed 12 documents and 52 memoranda of understanding. They reached noteworthy agreements on financial cooperation, including a currency swap agreement; private sector cooperation in third countries; innovation, including intellectual property rights; and maritime search and rescue.

Tokyo and Beijing also agreed on seeking further exchange between Japan’s Self-Defense Forces and China’s People’s Liberation Army, and on early resumption of negotiations to implement the 2008 agreement on joint resource development in the East China Sea. Reportedly, sensitive historical issues and the Taiwan Strait question were also discussed. Premier Li Keqiang officially invited Abe to the 2019 China–Japan–South Korea trilateral summit in China, and Abe invited Xi to come to Japan.

Chinese leaders are frustrated by the United States’ protectionist and ‘Sino-phobic’ attacks against China, and shared such concerns with Abe. As Shin Kawashima writes, the Chinese leadership ‘expressed their hope that Japan and China could combine forces to take the United States head on. But the likelihood of such a joint Japan–China push back against the United States is slim’.

Xi may make a state visit to Japan in 2019, but the areas of cooperation that Beijing and Tokyo could agree on would depend on the state of US–China relations at that time. If Beijing and Washington fail to reduce tensions, China could be tempted to further enhance its relations with Japan. But as a crucial US ally, Japan could be asked by Washington to join a united front against what it perceives to be China’s belligerent behaviour.

Japan would be put in a serious dilemma between its alliance with the United States, on the one hand, and its improving ties with China on the other. Ideally Japan could balance its relations with both countries to its own advantage — Tokyo could potentially gain leverage in its relationship with Beijing if it were able to avoid complying with Washington’s hard-line approach to China without discarding its alliance obligations. But in reality Tokyo may be forced to choose sides. Washington may ask Japan to show its loyalty through a commitment to shut out ‘malicious’ Chinese commercial activities from its market.

It is still too early to judge whether Japan will promote its bilateral relationship with China at the cost of its relationship with the United States. The Japanese government is carefully managing its place within the Japan–US–China triangle. It explains the restoration of Japan’s relations with China this year as an attempt to fix the relationship’s deterioration since 2012 and to persuade China to pursue fairer and more responsible behaviour in the international community. Tokyo rejects any interpretation that the restoration of Japan–China ties means it is tilting towards China or downgrading the importance of its alliance with the United States.

Japan’s long-term security concerns with China have not changed. The Japanese government has completed the process of reviewing its National Defense Program Guidelines in 2018. Japan is going to refurbish its helicopter destroyers to be able to carry US-designed stealth fighters and enhance its cross-domain defence capabilities.

Still, Japan does not share the same competitive position against China encapsulated in US Vice President Mike Pence’s October 2018 speech. Japan does not welcome the Trump administration’s ‘America First’ approach, even though Japan shares US concerns over Chinese trade practices. The Trump administration’s economic nationalism is against World Trade Organization rules and targets its own allies.

Furthermore, Japan is yet to articulate its own value-oriented approach against China, including a firm stance on religious freedom in China or on Taiwan, while it generally welcomes the US security commitment to the Indo-Pacific region.

The aim of Japanese diplomacy over the last 10 years has been to maintain the US-led, post-war international order in the Asia Pacific as the balance of power shifts. But Japan and the United States now has a gap to fill on their big picture views of the region, and Japan — which still rejects a China-centric order — is yet to come up with an alternative strategic vision. Recent behaviour suggests that Japan is aiming for a more inclusive regional dynamic. If there’s one thing for sure, it’s that Japan’s strategic dilemma has deepened in the time of Trump foreign policy.

Ryo Sahashi is a Professor of International Politics, Kanagawa University and a Research Fellow at the Japan Center for International Exchange.This essay is based on the author’s recent talk at East Asia Institute, Seoul and Institute of International Relations, National Chengchi University, Taipei.