What had long seemed Malaysia’s permanent government was humbled, and its anchor party — the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) — has been thrown into disarray.

The new government — a ruling bloc without a clear agenda brought together by Mahathir’s political wiliness, experience and familiarity with the Malaysian state — entered office largely unprepared. PH prevailed not upon its own political strength but as the vehicle and beneficiary of a groundswell of growing civil society activism.

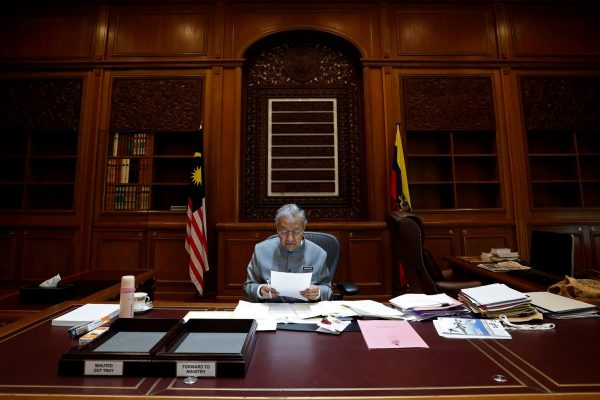

In its first six months in power, PH has signalled its key intentions by unshackling the long-suborned judiciary and initiating the prosecution of those responsible for the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) financial scandal. It has also made strong appointments to key positions, including the Attorney General and Chair of the Election Commission.

But its long-term strategic course remains vague. Speculation continues about the timing and implications of the political succession from Mahathir to Anwar Ibrahim, leader of the People’s Justice Party. Whereas Mahathir has long pulled the levers of state power, Anwar is less experienced. While Mahathir is a more single-minded promoter of Malay interests, he is viscerally a religious anti-clericalist. Anwar may be inter-communally more inclusive, but he is a soft and sentimental Islamist who has been amenable to hard Islamist influence.

As the PH regime feels its way forward, its adversaries are biding their time, waiting for it to stumble. But PH has some breathing space for the moment. It is hugely benefiting from the post-election collapse of the once commanding UMNO. Many of its elected state and federal representatives are defecting to the component parties of PH. Others are gravitating towards the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS).

But the longer-term implications of this tendency are towards the polarisation of Malaysian society and political life. There is a brutal contest between the fragmented forces of social democratic pluralism within the PH and religiously-driven Malay ethno-sectarians, made up of what is left of the UMNO and PAS.

Momentum is with the Malay ethno-sectarians. They are reviving efforts that began under Najib’s pre-election entente with PAS to gradually affirm the equal standing of the sharia and civil courts. Through new statutory reform of the civil law, they aim to increase the punishments for violations of Islamic criminal law — such as the consumption of alcohol and daytime eating during the fasting month — that the sharia courts may impose.

Such initiatives by the PAS–UMNO opposition will be used to place growing pressure on the authority of a divided, uncertain and hesitating PH ruling bloc. The PH government arose from bottom-up mobilisation, not coherent opposition party strength. Its adversaries now seek to bring it down by recourse to far more rowdy and intimidating forms of the same strategy.

As 2018 ends, the new government’s will is being jointly tested by PAS and UMNO, who marked the annual UN Human Rights Day by mobilising demonstrations and street-level opposition against the PH-promised proposal to ratify the UN International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. PAS and UMNO argue that ratification is incompatible with the Malaysian Constitution, whereas PH says it is not.

The division here turns upon the revisionist interpretation of the Constitution that UMNO began to promote in the 1980s, when its ideologues confected the notion that entrenched within the 1957 independence constitution — as the key tenet of the nation’s founding ‘social contract’ — is the principle of ketuanan Melayu (Malay ascendancy). This view embodies the Malay instance of so-called ethnic nationalism: the powerful political fantasy of living exclusively among one’s own people, people of one’s own kind, on one’s own preferred cultural and historical terms, undiluted and undisturbed by strangers and outsiders.

The PH government’s opponents proclaim that Islam is in peril, and that no one will save it but the Malays. They also argue that Malays, and their stake in the country, are in jeopardy and they can only be upheld through Islam. Devised to promote the UMNO–PAS entente since 2013, this rhetoric is now the theme of the growing opposition assault upon the PH government. It will provide the leitmotif of this new political era.

Clive Kessler is Emeritus Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of New South Wales.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2018 in review and the year ahead.