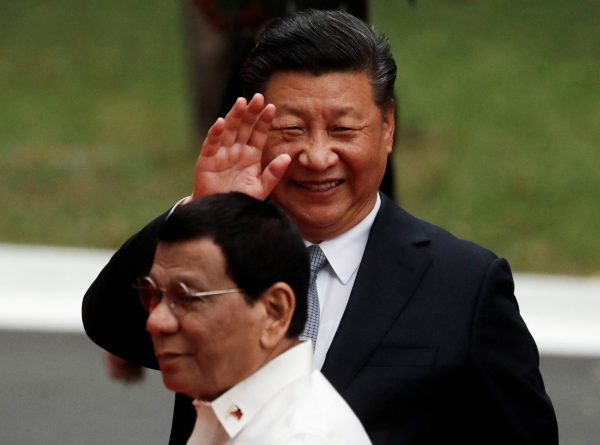

Despite high expectations, Xi’s visit failed to achieve any major breakthroughs. There was neither a firm resource-sharing agreement for the South China Sea nor a major announcement on the backlog of big-ticket Chinese infrastructure investments.

With little to show for his China-courting gambit, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has come under growing pressure to re-examine his foreign policy calculus — especially ahead of crucial midterm elections in 2019 that will serve as a referendum on his populist presidency.

In a region growing sceptical of Beijing’s overtures, the Philippines has emerged as an outlier — an island of rare optimism over its burgeoning bilateral relations with China.

Since coming to power in 2016, Duterte has effectively toed the Chinese line on the South China Sea disputes. He refuses to raise the Philippines’ landmark South China Sea arbitration ruling in talks with Beijing, has described the situation in the disputed waters as generally ‘stable’ and ASEAN–China relations as ‘excellent’, and rarely criticises Beijing’s relentless militarisation of claimed islands.

Operationally, Duterte has blocked US warships en route for freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea from using Philippine ports. He has also rejected US requests to preposition equipment and develop critical bases close to the disputed waters under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.

During Xi’s visit, both sides agreed to elevate their relations to a strategic partnership. Xi announced an agreement to ‘chart a clear course for China–Philippines relations’ and made it clear that China ‘will continue to do its modest best to help and support the Philippines’.

Yet of the 29 deals signed between the two countries, there was little indication that China will expedite its multi-billion dollar pledges of infrastructure investment in the Philippines. Almost all the signed deals were vague, non-binding agreements on pre-identified projects. Among the 10 proposed big-ticket Chinese infrastructure projects, so far only one (the Chico River Pump Irrigation Project, worth around US$60 million) has passed the preliminary stages of implementation.

Frustration seems to be building, with outspoken Philippine Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno openly lamenting the need for Xi to ‘put pressure on the speed of implementation of all these projects’.

Similarly, months after Duterte suggested ‘co-ownership’ of resources in disputed areas of the South China Sea, the two sides have failed to secure even the framework for an agreement on joint exploration of potential energy resources. They have only signed a memorandum of understanding on oil and gas development, with no specifications on where the potential projects would be.

The deadlock in negotiations is likely due to mounting domestic opposition, including from within the Philippine government bureaucracy, to any controversial and potentially illegal resource-sharing agreement with China. No less than Foreign Secretary Teddy Locsin proudly announced his pushback against ‘forces [within the government] saying we should come to an understanding’ with China.

The Armed Forces of the Philippines, which remains heavily sceptical about China’s intentions, reportedly also rejected a Chinese proposal for a Maritime and Air Liaison Mechanism in areas of overlapping claims in the South China Sea. For the military, any such agreement would indirectly legitimise China’s claims in the Philippine-claimed Spratly chain of islands.

Shortly after Xi’s departure, key statesmen aired their explicit opposition to any major compromise with China. Supreme Court Justice Antonio Carpio, the acting chief justice at the time, warned that any joint exploration or joint development deal with China in areas of overlapping claims would be unconstitutional. He went so far as to call China’s creeping maritime expansion the ‘gravest external threat’ to the Philippines since World War II.

Prominent politicians are also being more openly critical of closer ties with China ahead of the midterm elections. The latest surveys suggest that the vast majority of Filipinos are sceptical of China and would prefer that Duterte take a tougher stance in the South China Sea disputes.

The Senate is conducting several investigations into the reported influx of illegal Chinese workers, the proliferation of Chinese-run online casinos and the potential entry of a state-run Chinese enterprise into the Philippines’ telecommunications market. Prominent legislators such as Senator Grace Poe have openly raised national security concerns over a deluge of Chinese technology, capital and workers.

Far from falling into China’s orbit of influence, the Philippines remains in the midst of an intense internal debate over the future of its bilateral relations with Beijing. Crucially, there is deep opposition to any major compromise with Beijing in the South China Sea as well as uncertainty about large-scale Chinese investments.

Instead of solidifying bilateral ties, Xi’s visit seems to have only exposed internal fault lines and widespread scepticism in the Philippines over Duterte’s strategic flirtation with Beijing.

Richard Javad Heydarian is a Manila-based academic and author of The Rise of Duterte: A Populist Revolt Against Elite Democracy.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2018 in review and the year ahead.

A version of this article originally appeared here on Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.