At China’s initiative the SCO adopted the term ‘three evil forces’ to refer to terrorism, separatism and extremism. Countering these forces has served as the organisation’s foundation since its creation in 2001 as a replacement to the ‘Shanghai Five’ grouping of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. In 2002 the SCO created the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure, a standing organ responsible for security cooperation. China and the other SCO member states have conducted bilateral and multilateral anti-terrorism military drills on a regular basis since.

The SCO is sometimes regarded as an anti-West or anti-US regional collective security organisation. Although the US factor should not be overlooked, it was not critical to the organisation’s origins and development. Nor did the United States pay the SCO much initial attention.

Only from 2005 onwards did the SCO begin to take positions that aroused US anxiety. After the 11 September 2001 attacks, the United States stationed forces in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to support Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. After the Taliban regime’s overthrow, the United States continued to use the two bases. The 2005 ‘colour revolution’ in Kyrgyzstan was said to have some connection with US intervention, and Uzbekistan’s repression of the Andijan riot the same year was condemned by the US State Department.

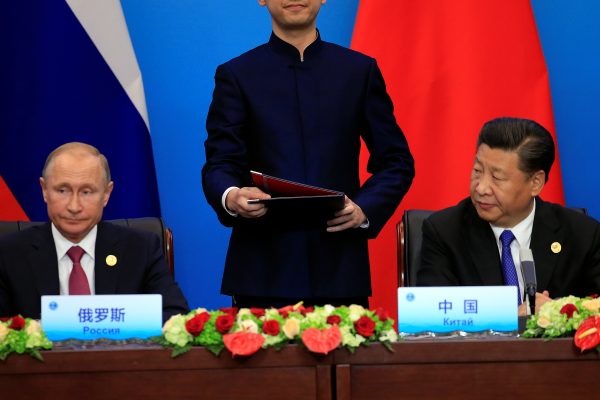

At the 2005 SCO summit the joint declaration suggested that the United States should set a timetable to withdraw its military bases from the two Central Asian nations. The subsequent shut down of the Khanabad base by Uzbekistan caused US uproar. At the same time the SCO invited Iran to participate in summit meetings as an observer. The large-scale ‘Mission of Peace 2005’ military drills conducted jointly by Chinese and Russian forces in the Russian Far East and China’s Shandong Province were also an important development. The United States began to pay more attention to the SCO, and its suspicion, distrust and criticism of the organisation increased.

The ongoing deterioration of Russia’s relations with the West and looming US–China confrontation might provide impetus for deepening cooperation among SCO member states, especially between China and Russia. But it is not in China’s interest to turn the organisation into an anti-West military alliance. Nor is there any evidence that Russia harbours the same intentions. For China, cooperation to combat the ‘three evil forces’ remains the organisation’s primary mission.

Economic cooperation is another important mission of the SCO and one of the organisation’s three pillars. But compared with security cooperation, economic achievements are few.

China is undoubtedly the locomotive for economic cooperation in the organisation, serving as the largest contributor to its administrative budget. China is also actively promoting establishing an SCO development bank and an SCO free trade agreement (FTA). But China’s promotion of regional economic integration within the SCO framework is not receiving a positive response.

In comparison with China, Russia is a relatively passive participant in SCO economic cooperation and attaches greater importance to security cooperation. Moscow is concerned with China’s economic expansion in Central Asia as a challenge to Russia-dominated Eurasian integration. Russia advocates for the expansion of SCO membership and supported India’s joining in 2017, partly to balance China’s power in the organisation. Some even argue that Russia tries to use the SCO to monitor, restrain and control China’s behaviour in Central Asia, traditionally a Russian sphere of influence.

Are Russia and China moving towards competition in Central Asia? The reality is that Russia enjoys much greater influence in Central Asia, and China does not have the will or the capability to drive Russia out. Central Asian states also remain cautious of China’s growing regional presence. Many are afraid of becoming too economically dependent on China as simply a natural-resource supplier to, and consumer market for, China.

The SCO and the Russia-dominated Eurasian Economic Union overlap in membership and functions. While the two institutions might fall into competition, they could also be partners. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 called for cooperation between the SCO and the then Eurasian Economic Community, which could deepen as the BRI develops.

US President Donald Trump’s protectionist trade policies may also provide an opportunity for greater economic cooperation among member states. The organisation is still considering the creation of an SCO Development Bank, as well as a Special Account that would provide financial support for project activities. An SCO FTA is also possible in the long run if approached in a step-by-step manner. Several countries fear that an FTA could lead to an influx of inexpensive Chinese goods, undermining national economies.

The SCO is already the world’s largest regional organisation in terms of population and economic potential. Its recent expansion following the accession of India and Pakistan may strengthen the organisation’s position in world politics. But wider membership could also lead to a loss of efficiency in SCO decision-making if competition between India and Pakistan and India and China hamper its functioning.

Zhang Xiaoming is Professor of International Relations and Associate Editor of The Journal of International Studies at the School of International Studies, Peking University.

A longer version of this article originally appeared here on Global Asia.