Wen has been using the term zhengzhi tizhi gaige, which was first used by the late Deng Xiaoping in 1986. Deng believed that political reform should accompany economic reform, but he never had the chance to articulate the substance of such political reform. The Tiananmen Square protests and subsequent crackdown in 1989 decisively changed the course of political reform in China. As a result, non-economic reforms post-Tiananmen have focused on increasing administrative capacity and accountability. These reforms have included anti-corruption campaigns, introduction of new laws such as the anti-monopoly and private property laws, and the limited formation of a civil society comprised of GONGOs (government-organised NGOs) and other government-friendly non-state actors. Deng most likely did not envision Western-style liberal democracy in the context of zhengzhi tizhe gaige.

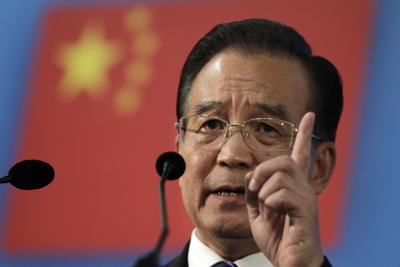

Premier Wen has been somewhat more forthcoming with his thoughts about political reform. In a meeting with overseas Chinese media while in New York, he stated, ‘I believe it [political reform] is to safeguard the freedoms and rights as provided under the constitution and the law . . . to have a relaxed political environment, so people can better express their independent spirit and creativity, and to allow them to enjoy free and all-round development.’ Quite poetic, but still nothing concrete resembling liberal democracy, which remains unlikely given China today where people like Liu Xiaobo remain in prison. While his calls for political reform are noble, it is difficult to divine whether his words signify a departure from past political reform, and more importantly, what his words mean within a government where it is more often what is not said that matters most.

A more plausible interpretation of Wen’s words might distill down to something more akin to political reform along the lines of what has been done for the past 20 years. Reforms instituted by the government seem designed to entrench its own hold on power. Thus, any reform that encourages the establishment of political parties, competitive elections, separation of powers or a system of checks and balances seems remote. However, the government is acutely aware that to move to the next level of economic growth and diffuse rising tensions among the population, certain reform is necessary. Such reforms could include revamping or abolishing the hukou or household registration system or education reform. Greater accountability of public officials, strengthening the letters and visits (xinfang) system, and streamlining the bureaucracy all fall within the ambit of political reform without compromising the party’s hold on power. Wen may be singing the right tune, but not enough people in China really care about political reform.

Recent commentary on Wen’s calls for political reform fail to acknowledge that many ordinary Chinese people are simply uninterested in politics. There are three main reasons for this lack of interest. First, is the uniquely Chinese social contract between the government and its people. As long as people can strive to buy their own flat, a BMW and a Louis Vuitton handbag, the government has their support. It’s a social contract built on attaining material wealth through continued economic growth or the ability to realise the ‘Chinese dream.’ The government exists to provide a means to achieve this material wealth. When growth threatens to falter, the government takes any and all steps to put it back on track. This social contract has reoriented the population’s focus from seeking political ideals through reform to issues of consumption and consumerism. The government is under no pressure at the moment to undertake any political reform deemed unnecessary to uphold this contract.

Second, the Chinese government has managed to de-politicise the majority of the population. A large number of Chinese people find politics to be uninteresting and express bemusement at how consumed Westerners are with politics. Many do not find political reform in the vein of liberal democracy to be relevant to their economic livelihood. The people within China who care most about Western-style political reform have either been harmonised by the government or are bloggers and other commentators who live underground, hiding from the government. Unfortunately they do not represent mainstream Chinese society, which is more concerned with economic than political issues.

The third factor is closely tied to the second, which is the 1989 Tiananmen protests and subsequent crackdown on the student-led movement. Tiananmen was a fulcrum for political reform in China; if successful it could have placed China on a very different political trajectory. Instead the government crushed the movement, either arresting the intellectuals who took part like Liu Xiaobo or forcing them to scatter around the world. In its wake, a generation of Chinese intellectuals emerged who are extremely proud of China’s rise as a global superpower. Any concerns that China’s authoritarian regime is holding the country back has been supplanted with strong support for the government and its accomplishments. Young people today know nothing about Tiananmen or what the students were asking for in their protests, except for what might be whispered in passing by those who remember. The lack of widespread knowledge about Liu’s Nobel peace prize, let alone who he is, should remind China-watchers how uninformed most of the population really is. The long-term effect of Tiananmen was the loss of a voice of a generation of intellectuals who could have risen to the ranks of power and primed the population for significant political reform.

In light of these three factors, any talk of political reform is nothing more than a shibboleth designed to appease those both inside and outside China who cling to the hope that liberal democracy will come to China sooner rather than later. It is easy for Wen to talk of a government that should be bound by its laws and constitution, but it should not be lost on China-watchers that most Chinese know little about their rights supposedly enshrined in the Chinese constitution or are even aware of recent current events affecting their country. The government’s string of successes have left the majority of the people even more inclined than ever to support the current regime and less willing to engage in the boring talk of political reform. Until the majority of Chinese people care enough to alter their social contract to encompass Western-style political reform, such talk will remain at best a theoretical tug-of-war played out behind the scenes at the highest echelons of government.

Peter M. Friedman is a lawyer in New York who just returned from a one-month appointment through the University of New Haven teaching American Business Law and the Regulatory Environment at Linyi Normal University in Linyi, China. He was an East Asia Forum Emerging Scholar in 2010.

There can be so much said about this so-called ‘Peace’ Prize. But I just want to say here in short that, when people in the West say, ‘you gotta follow the international order, international rule, international convention and international institution’, what they really mean is ‘you gotta follow the West dictated order, rule, convention and institution’. It has become so prevalent, so deep-rooted, so natural in their speech when talking about internationalization, globalization, cosmopolitanism, and of course, this so-called universal values that, the real underlying meaning is you (the non-west) ought to listen to us because we are the ones who not only stand on the tiptop of the global power ladder (certainly not for much longer, fortunately for the rest of the World), but also we have BBC and CNN to recognize our global moral authority. Nobel Peace Prize should indeed be renamed as “Nobel Prize for Promoting Western Global Moral Authority”.

I know I will be easily labelled as an anti-West bigot and an irrelevant and insignificant shouter. But anyone who has some sense of tolerance and understanding will find a bit of food for thought in my statement. At last, please ask these following questions to yourself: 1. When Nazi Germany can be brought into justice, why hasn’t Britain and America been brought to account for what they did in the Great Atlantic Slave Trade, the shocking depopulation of Native Americans and many many more unbelievable anti-human crimes which still exert large ensuing impact on today’s world affairs (namely, non-stop conflicts in south Asia, Africa, etc, and the de-industrialization of many colonized countries that seem doomed to fail, including India. Just look at their extreme lack of mobilization and organization, elements crucial for any industrialization to take place) 2. What is the definition of ‘Universal’? How universal is considered universal? 3. Why do we feel so uneasy and uncomfortable and even irritated when there are peoples out there who are fundamentally different from us, doing things different from us, thinking from a different angle? And why do we have to go and force those peoples to act like us? Can we just allow them to take care of their own business or their own mess, even though we are indeed living in the same planet? Seriously, hypocrisy only makes matters worse.

You make some valid points but I would have thought that the evidence is that Britain and America have been brought to account on the Great Slave Trade and depopulation of American natives and that is all that is asked of China now. There is no hypocrisy in that.

To those who are interested in this topic, please see:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/oct/08/liu-xiaobo-china#start-of-comments

My thought: I can’t help but commending this Guardian commentator’s insight, especially given that he’s actually from UK, a nation very often so proud of herself that a certain kind of superiority complex is well manifest in their media work. He’s certainly smart enough to realize how and why there has been a major backlash coming from China that many others in the West seem to have found it hard to understand. But those laymen’s comments below the article are showing something rather different, and indeed are those typical reactions and views of the ordinary westerners, which to some extent I feel regretable.

Whilst you make some interesting points, denouncing the west does little to make the political situation in China any better.

But in answer to your questions:

1. It must be remembered that this happened during a time when enslavement was the norm everywhere, such as in 17t century Manchuria where entire generations of Chinese were enslaved (that is, enslavement even became hereditary) to the one family. In short – people just didn’t know any better back then. However, whilst I am by no means trying to relieve the Britons and Americans of the moral culpability of their history, it is disingenuous to suggest that the sins of their fathers should preclude them from having any say in the 21st century. Rather, I would think it is more important to look to who is doing the right thing now, and who has done more to improve the conditions of human rights. And whilst American and Britain are by no means poster-boys for morality fairness, it would take a conspiracy-theorist to say that they have no moral authority, especially compared to the majority of governments these days.

Moreover, it is overly simplistic to blame the great slave trade and colonisation for all of South Asia and Africa’s problems (for example, one might suggest that if China didn’t sell arms to the Sudan, or stopped blocking UN resolutions to send peacekeeping troops before it was too late, the atrocities in Darfour would have been greatly reduced).

2. If you’re referring to the “universal” in the “universal declaration of human rights”, which is what people commonly refer to when they talk about “universal values, the UDHR was formulated by representatives from all continents and adopted unaimously by all signatories to the UN (except for the abstentia of a few such as apartheid south africa). The values enunciated by this charter are intrinsic to all human beings – by virtue of being human beings – and I would challenge you to come up with a reason why any one group of people are any less deserving of those rights than another group.

3. This is indeed a good question you should ask the Chinese government – “Why do you feel so uneasy and uncomfortable and even irritated when there are people out there who are fundamentally different from you, doing things different from you, thinking from a different angle? And why do you have to go and force these people to act like you? Can you just allow them to take care of their own business or their own mess, even though we are indeed living in the same planet?” – especially in light of Liu Xiabo’s continuing imprisonment for…well…pretty much just thinking from a different angle.

But i digress, as i suspect the real meaning of your third question is “why do other countries feel uneasy about how CHINA (cf. people) acts, and why don’t other countries just allow china mind its own business or create its own mess?”. The crucial point is, China is not a person, it is a state. And when it comes to human rights, this is an area where the armour of sovereignty must be pierced. To quote a famous dissident ““[i]f human rights issues are the internal affairs of a country and the government decides not to respect human rights, do human rights simply cease to exist as a problem?”.

Dear Janet,

You make some interesting points as well, and your basic argument is totally in my expectation as I’ve come aross so many of this sort in my discussion with the smart people from your ‘camp’ (if you may).

Firstly, just labelling someone you don’t agree with as a ‘conspiracy-theorist’ (as such a supposedly neutral term has been painted as a term of negativity in the post-70’s western culture of political correctness the same applies to other supposedly neutral terms such as ‘nationalism’ and ‘propaganda’: e.g. the Chinese = narrow-minded nationalism while the West=applaudable patriotism; the Chinese media= the mouthpiece and a part of propaganda machine of the CCP while BBC and CNN or NPR = the objective authoritative view of the world.) does not make your argument any stronger and convincing.

Secondly, “universal declaration of human rights” that you mentioned can also be critically questioned. While it’s certainly an ultimate ideal for many of us to strive for, (especially for the Westerners whose philosophical mindset is the main cause of this ‘declaration’) it’s not true that ‘the values enunciated by this charter are intrinsic to all human beings – by virtue of being human beings’. Your conclusion is not conclusive, at least anthropologically speaking. Not to even mention that the UN charter and many other international institutions are by no means univerally accepted, as the Power of Nations is the crucial factor that determines who invents or leads the international institutions. To this you simply cannot dismiss.

Thirdly, to anyone who is bombarded by the overwhelming media products of the West, it’s just the fact that the people in the West have been getting much more anxious about their future than they should have in the face of the re-emergence of China. And that’s why I raised those questions to my Western friends.

And at last, the nations or the peoples of the world certainly can come together and discuss the issues of human rights, to try the best to better our conditions. However, no one likes to be in the conversation where one talks to another in a self-righteous way.

Cheers

Dear Peter and Janet,

I appreciate that you’ve acknowledged some of my valid points. However, I cannot help but wondering what exactly those evidences that you mean in regard to UK and US having been brought to account for their crimes against humanity in the Great Atlantic Slave Trade and depopulation of American natives, and in many many more cases, including disgraceful treatments to the Aboriginal people in Australia. Don’t tell me that by saying ‘sorry’ is enough to get away with it. Not to mention that such a ‘sorry’ gesture had come so late that so many victims had long missed to know it will ever happen … And don’t tell me that because those terrible crimes took place a long time ago that they can also get away with it easily. Not to mention recent crimes against humanity in their-led invasion in Iraq and Afghanistan. If you recognise these, and argue that, ‘at least, American citizens and the people living in the West are enjoying greater freedom of doing almost all sorts of things that are not otherwise the case in the rest of the world.’ I would sincerely suggest you a very different story, a very different way of looking at the world that you’ve been brought up in. Due to the forum limitation, I can just roughly suggest you to study or even glimpse the current race issues in US and ethnic integration issues in Europe. (e.g. race differences in all regards in US; ethnic groups differences in all regards in Europe, especially in ‘old Europe’ , French sending Roma people back to Romania. German Chancellor Merkle just declared German failure in their attempt to achieve Multiculturalism few days ago, etc.) And, as important as to study these things, you may also have to know a bit of history regarding how Western- style democrac(ies) have come into today’s forms. (e.g. western nations’ arguably unique geographic, philosophical and cultural characteristics; the close relationship between the capacity to build liberal democracy and the results of colonization, applied to both the colonizer and the colonized.) This effort will also inevitably involve learning how democracies are different from each other even in the Western world itself; what is the cost of having a democracy, especially of having a particular western-style democracy that the West seems to only be able to appreciate.

Anyway, hopefully by the time you’ve done all these, you may find even more valid points in my argument. I totally understand where you come from, and I daringly assume that you and many others who read my post will find my argument a bit hard to swallow, in the sense that it’s completely in contradiction to whatever values (or you may call it ‘universal’) you’ve been brought up with. But please, take it easy, just with a bit of tolerance and understanding that the Western pluralists have been always keen to advocate, you will eventually realize many of the super hypocrisies in the Western discourse.

Cheers,

P.S If interested, also see what is the Western response when facing Egypt and China’s demand to return all the looted relics.

Labelling someone as a “conspiracy-theorist” simply because i disagree with them is counter-productive. But I didn’t do that. And equally counter-productive are broad-based insinuations of western arrogance in assuming that the west self-congratulates itself for its “applaudable patriotism” whilst at the same time denouncing “narrow-minded Chinese nationalism”, and think of their news outlets as the authoritarian view of the world.

Whilst the UDHR is still open to criticsm, I would be interested to know how is it “by no means universally accepted” when the overwhelming majority of the world are signatories to both the UN Charter and the UDHR. Did they fail to read the fine print before they signed? Moreover, i find it confusing that whilst on the one hand, you acknowledge that the principals of the UDHR are what we should all strive to achieve, you seem to argue on the other hand that it cannot apply because it is not “universally” accepted.

It is surprising that you are not aware of how the Australian government, as well as many other Australian institutons (most notably its High Court), have contributed to the reconciliation and healing of the Aboriginal people. Policies range from special medical care to welfare assistance, to subsidies, land grants, etc. Whether or not the policies work is another story. But the point is that they have acknowledge the wrong done in the past, and are trying to find the best way to move forward. I would think that this is the very best way of bringing into account their crimes against the Aborigines? What more do you want? To trial them in a international criminal court for a crime that wasn’t recognised when it was perpetrated? And if so, then just about every country in the world should stand trial there was a point of time in history when men were ignorant of the respect for their fellow human beings.

Moreover, it taks a pretty giant leap of imagination to connect freedom of speech and democracy with the race tensions in Europe and the States. The causes of these issues are cultural, social, economic, but least of all because these areas have a large relative population of immigrants all with different cultural backgrounds.

In addressing the history of democracy, you seem to argue that democracy only works in cirucmstances peculiar to western countries. What about Japan, South Korea? Sure democracy is not a perfect system, but no one is suggesting that one style of democracy should be applied to all nations. If this were the case, then even America and Australia would be at ideological loggerheads. What’s important is that the crux of democracy is the ability of a nation’s people to choose their own destiny.

At the end of the day, I don’t disgree with you because i find what you’re saying hard to swallow. I disagree because i find the fallacies in your arguments hard to overcome.

Dear Janet,

First of all, “it would take a conspiracy-theorist to say that they have no moral authority, especially compared to the majority of governments these days.” It’s your very own word. That’s why I said what I said in the first paragraph of my counter-argument. Just try to google it you’ll find in most cases, in describing the Chinese media, there’ll be words in front of it such as ‘state-owned’, ‘Communist Party’s mouth piece’, ‘narrow-mindedly nationalist’. So here it is.

For your second counter-argument, I have to say there’s a serious naivety on your part that assuming just because ‘the overwhelming majority of the world are signatories to both the UN Charter and the UDHR.’ They then must have truly accepted what they have signed. When the West, as the most powerful group of nations, put on a new agenda (such as ‘human rights’ and the latest one, ‘green economy’), which always looks morally superior from outside, you think other nations dare not to follow suit? What would they look like if they choose not to? For those who not following up the agenda set by the West, I guess the label of ‘evil country’ would be ready for them. And those so-called ‘NGOs’ such as Human Rights Watch (heavily funded just recently by hedge fund tycoon George Soros) would certainly pop up and do the job that they’ve been assigned up to.

Thirdly, I’m much more aware than you realize of the relationship between the indigenous Australians and the White Australians. You think, by acknowledging the wrong done in the past is the very best way of bringing into account their crimes against the Aborigine. I will say, firstly Germans would feel uncomfortable and unfair about your statement. Can a murder or a robber escape from their crimes by saying they were just ignorant at the time of crime? Not to mention what the Britons and the Americans did in the past (but not so long ago) have had prolonged destructive impact on the rest of the world. You miss my point if you think I just want to put them on international trial (which no one will think it will work). My point simply is that discussing the delicate issues such as human rights will have to have all discussants pay respect to each other, and maybe, and only maybe, we can get something constructively solid out of it. The world affair is so complicated that its complexity stretches in time, extends in place, and thickens in tension. By awarding a prisoner of a nation Nobel Peace Prize does not contribute in a good way to this delicate discussion.

For your third counter-argument on race issues in U.S and Europe, I assume you mean U.S. and Europe have done relatively well and should be forgiven about those setbacks given that they allow their citizens freedom of speech and have democracies in place which sometimes make their ‘harmonious society’ hard to achieve. In linking with your fourth point, I will argue that you actually agree with me that not many nations on this planet are philosophically compatible with the Western-style democracies. Moreover, they’re fundamentally not compatible with western cultures or western ways of thinking. Samuel Huntington is right on this that a clash of civilizations is happening within the Western world here and now, and will be continuing for a very long time to come. And also importantly, it’s not one-way straight that immigrants do not want to integrate, but the locals do not want to accept them as a member of the family.

You mentioned Japan and South Korea as the examples to show me non-Western nations can indeed have their democracies. Yes, sure. The people in Mainland China are watching closely how their compatriots are doing democracy in Taiwan. And we (the Mainlanders and the islanders) will be doing much better after all these learning and practicing when the Mainland and the island of Taiwan unite in the near future. You see any similarities among Japan, South Korea and the island of Taiwan? They all have their GDP per capita above US$ 6000~7000. On this I agree with Francis Fukuyama that for any truly meaningful political reform to take place one nation has to have a substantial economic and social base to support. You mentioned that “the crux of democracy is the ability of a nation’s people to choose their own destiny.” The world is much complicated than this simple ideal. The ‘people’, is such a vague term. Who represents the ‘people’, by how many they can be seen as the representatives of the ‘people’? Furthermore, the ‘people’ can very often make mistake in choosing their own destiny. And those people of developing world cannot afford to make mistake, certainly the Chinese people cannot. We will have to take our political reform step by step on our own terms, set by our own pace. Just like our currency, no one will ever move us like they did to Germans and Japanese and many others.

If you find the fallacies in my argument hard to overcome, I guess I must feel sorry for myself. But on the contrary, I find your argument hard to overcome its inborn errors stemming from perhaps natural inclination towards self-righteousness unique to so many westerners.

(simplified version)