At one end of the spectrum it is postulated that reform is impossible and would inevitably open the country up to information the regime has worked so hard to keep out, especially about South Korea’s economic prosperity. Also, it is argued, reform would instigate a backlash from the military and party elites associated with non-productive sectors of the economy. All this would then lead to a legitimacy crisis. Indeed, as best argued by Andrei Lankov, the contest of legitimacy between North and South to rule the entire Korean Peninsula and knowledge of just how much richer the South is poses a deep danger to North Korea.

But blanket dismissal of reform as a possibility fails to confront the shape and pace potential reform might take. Specific reforms would affect regime legitimacy in different ways, some destabilizing it, and some bolstering it, and this needs deeper analysis.

Moreover, the commentators probably already underestimate the increasing flow of illicit information penetrating North Korean society and may have a too one-dimensional view of regime legitimacy. For North Koreans themselves, influenced as they are by the political incentives and the ideological trappings of a crumbling system that has nonetheless changed in significant ways over the past decade and more, greater information about who is richer should not be assumed to automatically push them to overthrow the regime. The standard of living of the people has traditionally been de-emphasised as a source of regime legitimacy. Upholding the moral virtues of the Korean people and protecting them from hostile forces outside in the context of an unconcluded Korean War, has had greater priority. The standard of living is only recently making a very slow comeback now that North Korea has proclaimed itself a nuclear power, and with 2012 being celebrated as the gateway to a strong and prosperous nation there are ambitions to be fulfilled. As long as there are US troops in the South and the growing wealth inequality there to nominate as its weakness, North Korean propaganda (along with the right balance of fear and economic incentives) may well retain traction among the North Korean citizenry in the face of increasing information flows, even though that may seem ludicrous to the outside observer. Propagandists continue to pass off South Korean wealth as the result of collaboration with ‘evil US imperialists’.

As for possible backlash from the military and party elites, this is of course something to which Kim Jong-un will need to pay close attention, but not necessarily as a zero-sum game. If Kim Jong-un is indeed serious about shifting away from an economic structure where the military simply depletes society of resources, he will have to keep a lesson from Deng Xiaoping in mind: about the military’s role in the economy, the danger of breaking their rice bowl, and the need to craft creative ways to allow the military to run its own enterprises, make money, and become a major stakeholder in economic reforms. There is some evidence that this may be in train.

At the other end of the spectrum, there has been media frenzy about the possibility of rapid and radical reform including wild claims that North Korea was set to ditch its planned economy and state rationing system. Rumours also swirled about the second session of the Supreme People’s Assembly on September 25, which in the end gave few clues about Kim Jong-un’s intended reform path. This frenzy seems to have stemmed from a misinterpretation of North Korea’s experimentation with agricultural reform. What actually appears to be happening is that three counties in Yangkang province, as a trial, will reduce the size of cooperative farms from 10-25 to 4-6 people, allowing farmers to keep 30 per cent of their output, and having the state purchase the remaining 70 per cent at market prices. And to keep this project on track the agriculture minister was replaced earlier this month. These reports have then been distorted through a game of Chinese whispers among news organizations. The opaqueness of North Korea and the need to protect the identity of in-country sources from being punished for speaking out has, in an alarming trend, been abused as a license to publish any old rumours. Yet the development is significant as it portends the same kind of experimentation with ‘household reform’ that China began in the late 1970s.

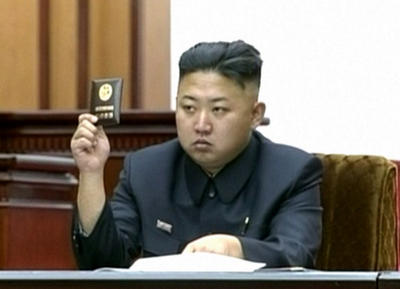

So what is really going on regarding reform in North Korea? And is Kim Jong-un the reformer we might want him to be?

First, the movement toward economic improvements and raising the standard of living for ordinary North Koreans was visible in the latter days of Kim Jong-il’s rule. The joint new year’s editorial of the major newspapers — North Korea’s most important domestic policy statement — in 2010 wrote of bringing ‘about a radical turn in the people’s standard of living by accelerating the development of light industry and agriculture’. The numbers of restaurants, cars and mobile phones on the streets of Pyongyang visibly increased in 2011.

Second, since Kim Jong-un took power, he has given strong indications that he is serious about improving the economy and the standard of living of ordinary North Koreans. In addition to the experiments in agriculture mentioned above, Kim Jong-un has given two public speeches in which he spoke rather frankly about economic matters, pledging that North Koreans would never have to tighten their belts again, and speaking about land management and being on guard against giving away North Korea’s precious natural resources on the cheap. He lifted economic diplomacy, going beyond the usual suspects — China and Russia — and sending delegations to Southeast Asian nations in a bid to drum up foreign investment.

This is still early days. Kim Jong-un has not even been in power for one year, no economic reform plan has been enunciated, and any reforms, such as those in agriculture, are only experimental and at this stage easily reversible. The pace of reform is likely to be frustratingly slow given the need to maintain a balance between continuity and change.

If economic reform is going to be successful over the long-term there are a number of challenges that must be addressed. For one, Kim Jong-un will need to continue to consolidate his grip on power. Social order will help him pursue his agenda effectively. Also, a conducive regional security environment will be crucial. North Korea will need to expand its trading partners beyond China, South Korea via Kaesong, and what other minimal trade it has. Normalized diplomatic relations with the United States and Japan are a must. Even if the nuclear issue is not resolved, US recognition of the DPRK’s right to exist as a state would go a long way to encouraging the expansion of trade in goods unrelated to nuclear sanctions which remain deeply affected by the embargoes. At present potential trade and investment partners of North Korea are spooked, and fear the stigma of being labeled sanctions violators. Lastly, Kim Jong-un will need to ensure that he, his advisors, and those he appoints to formulate and implement policy have the requisite economic knowledge for success. That’s where resumption of the Australian economic training programs are in everyone’s interest.

Ben Ascione is a Monbukagakusho Scholar and MA candidate in international relations at the Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies, Waseda University, a researcher at the Japan Center for International Exchange, and an associate editor at the EAF Japan and North Korea desks.