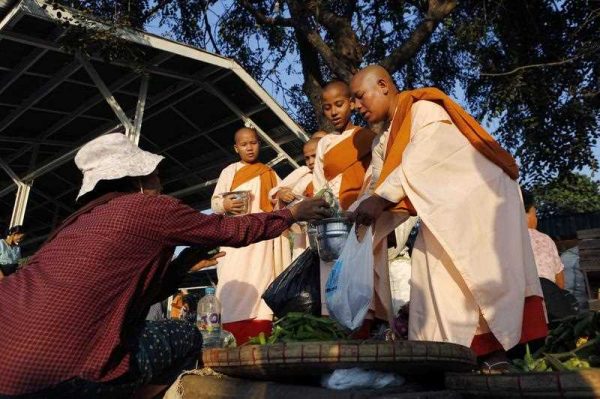

How should we interpret this scene? Is it simply an innocent example of imparting religious values to the next generation or another worrying indication of the insidious spread of anti-Muslim nationalism in Myanmar? Frustratingly, the answer might be both, which makes it difficult to know how to respond or intervene. In periods of rapid transition and modernisation, people develop an intensified concern regarding the loss of their cultural identity and traditions. These anxieties were present in colonial Burma in the first decades of the twentieth century and galvanised the nationalist movement at the time; they are also pervasive in contemporary Myanmar.

The outside world has focused almost exclusively on the admittedly worrying anti-Muslim orientation of the Buddhist nationalist movement in Myanmar, but another emerging aspect of contemporary Buddhist practice in Myanmar demonstrates that the relationship between religion and nationalism is complex and must be analysed carefully. Since about 2010, different organisations have been creating networks of Buddhist Sunday schools in an attempt to instill Buddhist values in children, who, they are worried, will not grow up with the same religious understanding or devotion of previous generations.

The rapid expansion of these classes has seen some organisations teaching tens of thousands of students in hundreds of locations across the country. Where they are centrally organised, the level of top-down control varies. MaBaTha (the Organisation for the Protection of Race and Religion, that has been promoting a series of discriminatory laws connected to religion) merely sells a curriculum book and invites interested lay people to develop their own classes. At the other end of the spectrum, a group called the Dhamma School Foundation has a much greater level of organisation, with a detailed teacher training curriculum, the involvement of monks in teaching, and regular evaluations including site visits. Nowhere do these classes supplant the public education that children receive, but, as might be expected in a Buddhist majority country, the line between the two is not always clear.

Some might be concerned that these informal schools will simply be vehicles to inculcate children in an increasingly virulent anti-Muslim nationalism. But the curricula for most are relatively innocuous, teaching exactly the kinds of values one would want to promote among Buddhists in Myanmar.

Does this mean we can champion these schools as an effective response to religious conflict in the country? Unfortunately, the answer is probably no, at least not until there also develops an alternative understanding of the appropriate ways to promote and protect Buddhism.

The dominant framework within which most Buddhists in Myanmar at the moment are interpreting the notion of protecting their religion is against the external threat of Islam. Teaching materials themselves may not be problematic but when they are used by monks who also spread misinformed rumours and negative images of Muslims, the message children get is not that Buddhist values should be promoted to make Myanmar a more peaceful country but that Buddhist identity is under threat and must be secured against an outside enemy. More worryingly, even when these classes are not linked to explicit anti-Muslim rhetoric, students and teachers are likely to interpret their lessons within the context of the currently dominant narrative of Buddhism in Myanmar in danger of being overwhelmed by Islam.

Well-intentioned but incautious outside voices seeking to address Myanmar’s religious conflict have at times exacerbated tensions. For example, the Time magazine article about hardline Buddhist monk U Wirathu merely resulted in a circling of the wagons. A critique of one monk’s reprehensible preaching was interpreted as an attack on Buddhism writ large.

Buddhist Sunday Schools are part of a (in many ways laudable) response by Burmese Buddhists to the anxieties they are facing regarding the opening up of their country to outside influences. Some even emphasise the kinds of inclusive and tolerant practices that will be a necessary foundation of a religiously plural Myanmar. Criticising or dismissing them as simply vehicles for the spread of religious bigotry would be counterproductive, alienating many Buddhists whose main engagement with a group like MaBaTha might be in its pro-Buddhist guise rather than its anti-Muslim orientation. But one aspect cannot be easily separated from the other.

It will be necessary to clearly communicate to Burmese Buddhists that, while their attempts to promote the best values of their religion are admirable, unless the narrative that posits Buddhism as under threat from Islam is altered, there is a danger that their efforts could actually encourage an ignorant and violent intolerance that is the very opposite of what the Buddha taught.

Matthew J Walton is the Aung San Suu Kyi Senior Research Fellow in Modern Burmese Studies at St Antony’s College, University of Oxford.

“How should we interpret this scene? ….how to respond or intervene.” ???

It’s Sunday school in a different country by a Buddhist monk.

Your words are somewhat arrogant and presumptuous- why do you need to “intervene” at all?

Let’s turn this around. A priest/pastor in England is teaching in Sunday school in a town and teaches some parts of the Bible.

Will you also say- how should you intervene?

Adrian, thank you for your comment. I do take your point about the arrogance of assuming that one ought to intervene in another country’s business. I would say that, while there’s a normative discussion to be had there, the reality is that many different actors (other countries, INGOS, etc) **are** currently engaged with politics in Myanmar and are looking to intervene (or help actors in Myanmar to intervene), especially in situations that could cause further violence or conflict.

In that way, this article is intended as a warning to recognize that any intervention to stop the spread of religious hatred must be very careful to understand the dynamics and not alienate Buddhists who don’t want to cultivate anti-Muslim sentiment but also don’t want to be demonized for simply supporting their own religion.

I would actually disagree with the implication of your counter-example. We do intervene in situations like that all the time. National and local governments in the West have occasionally sought to intervene in religious teaching when it is thought to be promoting hatred or violence.

There is also regular public debate in many countries not just about the appropriate government response, but about self-regulation within religious communities. Especially in situations where religious teaching seems to be connected to or possibly fueling violence in society (and I think we could say that this is the case in Myanmar today), we do publicly address the issue and wonder about the appropriateness of what is taught in private religious contexts.

While this article is mainly directed towards an external audience, this is also a conversation I have with friends and colleagues in Myanmar. I do believe that there is a danger of even well-intentioned Buddhist teaching right now supporting a worrying narrative that Buddhism is under threat and Islam is the cause. I would like to work with my Buddhist colleagues in Myanmar to ensure that their work to strengthen Buddhist practice within their communities is self-consciously challenging the dominant anti-Muslim framing, since religious teaching is vitally important, yet also fraught in the current context.

Apologies for a rather long response and again thank you for your comment and question.

Sir

I am well informed from the late 1970s until to present that Burma’s Buddhist communities are just living with the nature of ‘komma’ (fate) not by pluralism such as we call ‘democracy’. As we are taught by parents, teachers and monks, our intention (cetana) is the cause of our fate (outcome of life) from early childhood. Sunday School is not much different from the lod Summer Buddha’s Teaching Class that I attended in late 1980s in Mon State. In fact, at the age of 9, I left the public primary school to stay at local Monastic education system in rural Mon village. Buddha’s teaching to the children is simply to improve ethical behavior in my own experience during my 10 years inside the monastery. The monks and novices recite the Pali text as a normal way of learning the text (Mon, Burmese or Pali). After the passing away (Enlightenment) of Gotama Buddha in 2554 years in (2014), the preservation of the Pali text, and other texts either in Mon or Burmese were practiced by the non-Monkshood. They were the practices of teaching by both Mon and Burma’s Kings from the late 11th to 17th A.D. However, the curriculum was cross-checked by respected scholars in two ways. The Text scholars from the Pali University and the Content scholars from people like you from Oxford University. I left the monastery in 1994, but at the age of 45 now, I am well informed that many Buddhist monks in Burma preserved the Teravada ways (instruction of the elder monks to the junior monks in teaching), but these monks obey the rules of monks (Vinaya), and also learn the Pali text (Pitacata) with full insight meditation that enables peace, inner peace and pathway to reach the end of suffering (nivana). If Burma seeks to restore communal peace, law and orders in the context of Buddhism, the only option is whether our new and current leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi have the courage to warn the Buddhist monks that they shall by observing the ‘vinaya’, in stead of following a political movement. In the case, as Prof. Ling (1979) recounted in his book titled, ‘Buddhism, Imperialism and Wa’,Buddhist monks and other lay-Buddhists have been prepared to die to protect Buddha’s teaching and cultural practices if other faiths intervene or invade their faith (Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha – Three Gems) as we known them. In my personal view, The Sunday School is a revival of the spiritual well-being of children as well as giving children ethical learning about social and emotional wellbeing. The monks are the servants of the laymen, and therefore, if the laymen request or invite them either to teach or pray, they will perform that duty based on the rule of monks’ role to fulfill the will of the laymen. It would be my wish that western scholars and researches either live and learn the Mon, Burmse or Pali text for further examination on the field of spirituality. Sir, you will be rewarded if you have studied the Tipitaca (the text of Buddha’s teaching) instead of picking up one angle to another. Above all, India’s Buddhist communities only survived for over 800-900 years after the passing away of Buddha Gotama, but the Mon / Burma’s Buddhist communities have been preserving this unique practice so that is has lasted to the present. Buddha only gives guidance (teaching) but has never forced anyone to be his own follower unless they consent themselves to the Buddha’s Sasana (Buddha’s Institute”. I thank you for your article with the hope that the ‘truth’ of being a human will prevail when the man cultivates his own mind from the hinderance of, and liberation from ‘being’ in the universe. Thank you for your effort

Under the apparent balanced analysis, the author seems to pursue a pro-minority agenda; one which may be politically correct in the West, but is a sheer fallacy when put in an history perspective. There is something intellectually devious in establishing a parallel between sunday confessional teachings and any anti-islam rethoric and proselytism. “students and teachers are likely to interpret their lessons within the context of the currently dominant narrative of Buddhism in Myanmar in danger of being overwhelmed by Islam” Has the author gathered any evidence that the sunday schools actually convey an anti-islam stance? Has the author only taken care of reading the contents of teachings? Or just ‘discussed with Myanmar friend who believe…’ It would seem that basic research requires to get the facts right, wouldn’t it?

Now if the author would read both regional history (the Islam question in India, in South Thailand), and learn the basic tenets of the Islam faith, for which one of the sacred duty is active proselytism and fighting the infidels, he might conclude that all historical precedents point towards an actual risk of Islam communities progressively mining and destroying the social and religious values around them. The fact that Islam does not allow free interpretation and exegesis of the Scripture, open the way to islamism and terrorism as ultimate and righteous ways to promote the Faith. As long as this issue is not addressed, one would have difficulties in accepting criticism on ways other religions may use to assert their right to existence. And the fact that Bouddhism may appear a vehicle for certain political movement looks paltry in regard with the political games in which Islam is an hostage.