The Reserve Bank of India governor, Raghuram Rajan, has been more sanguine: he expects growth to increase by 1 percentage point each year after 2015 until about 2017.

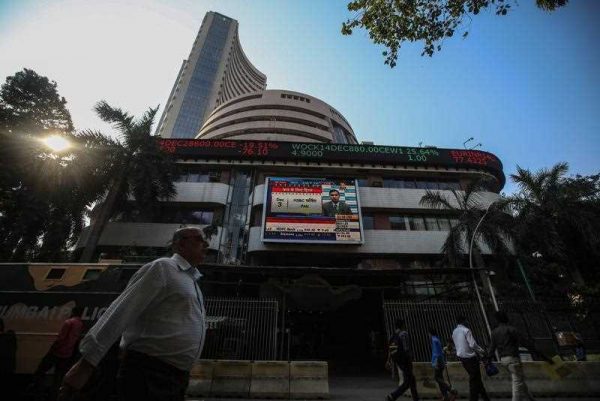

Confidence in the Indian economy has soared since the election of the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The stock market has rebounded with strong foreign institutional investment inflows. FDI is also slated to pick up, particularly with the enactment of reforms such as raising FDI limits in insurance and railways, among others, and the relaxation of labour laws.

More importantly, domestic saving and investment are expected to pick up in a manner that boosts growth and lowers the current account deficit. This will be thanks to a sharp drop in the central government’s fiscal deficit, and the perceived improvement in governance and political decision-making. Increased decentralisation of governance has also helped as has the sharp fall in the price of petroleum in international markets. The real possibility of implementing a GST by 2016 has further boosted confidence.

However, there are several political challenges facing policymakers. Although Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — in conjunction with its coalition, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) — has a majority in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, it does not have a majority in the Rajya Sabha, the upper house. More members of the ruling NDA could enter the Rajya Sabha following recent BJP state victories in Haryana and Maharashtra, since state legislatures pick most of the members of the upper house.

The BJP could form an alliance in Maharashtra with the Shiv Sena party, which would mean that Shiv Sena’s legislators in the upper house would support the NDA federally. The NDA is also likely to do well in state elections taking place in Jharkhand and in Jammu and Kashmir. This could also add to the stock of Rajya Sabha members from the NDA. Looking ahead, the NDA could even have a majority in both houses following state elections in Bihar in 2015, West Bengal in 2016 and Uttar Pradesh in 2017. Major reforms are in prospect and could be rolled out in the next few years.

Despite this optimism, the Indian economy faces some challenges in 2015.

Unlike in the early 2000s, India cannot rely on a rapidly growing global economy to boost exports and, hence, growth. Economic conditions in India’s major trading partners appear lacklustre. Even though US output growth figures look optimistic, employment growth since the global financial crisis has been meagre (after adjusting for changes in labour force participation rates). Nor do Japanese and European growth rates inspire much hope.

As Governor Rajan has pointed out, this time around India will have to look inward to grow faster. Consolidation of the economy, afflicted by the policy paralysis of the previous government, has taken almost six months. This is why the pace of reforms has been slow. Future reforms in 2015 will depend critically on the NDA’s ability to garner support among opposition party legislators in the upper house, or joint sessions of parliament to pass crucial bills.

Prime Minister Modi has emphasised the potential of his ‘Make in India’ policy to create jobs. This should probably be recast as a ‘Make in India for Indian consumption’ policy. The manufacturing sector will have a critical role to play in this. This sector has, however, been languishing under the burden of high interest rates and lower margins because of a wage-price spiral that was set off by the previous bout of inflation. Now that wholesale price inflation has almost come to a halt and inflationary expectations are subdued, there is a case for lowering interest rates. At the current juncture, CPI inflation, which is already low, is better managed with supply-side policies.

There are certainly challenges for the Indian economy in 2015. But prospects are good, and will be even better in the years following.

Raghbendra Jha is head of the Arndt-Corden Department of Economics and Rajiv Gandhi Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy, ANU. This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2014 in review and the year ahead.