Finally rated at a magnitude of 9.0, the earthquake was the most powerful recorded in Japan and the third most powerful in the world since modern measurements have been taken in 1900. Over 18,000 people perished or were lost, most of them in the tsunami that followed the quake. The tsunami reached heights of over 40 metres and washed through three to four storey buildings as it swept cars, trucks, boats and planes away on its path inland. The tsunami inundated the Fukushima nuclear facility causing level 7 meltdowns at three reactors and requiring evacuations within a radius of up to 20 kilometres. The earthquake shifted Honshu, Japan’s main island, 2.4 metres to the east towards the Americas and its force moved the earth on its axis by an estimated 10–25 centimetres.

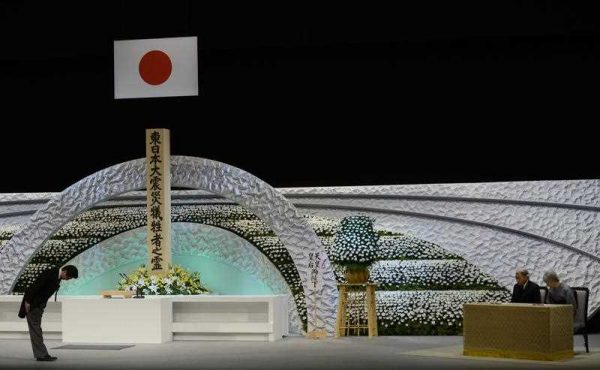

These are the terrifyingly impressive physical effects of the Tohoku tragedy. The way in which the impact effects of a disaster on this scale were managed is a testimony to the resilience and capacity of the Japanese people — not only their remarkable capacity to face natural calamity stoically but also the social capital, skills and organisational know-how they brought to dealing with it on a grand scale and with great efficiency. Casualties would have been much higher if systems had not been put in place or if warning systems had not been heeded in coping with the event. The national government, Self Defense Forces and civil society swung into action expeditiously. Both civilian and emergency services displayed remarkable effectiveness in coping with the immediate disaster. International assistance was forthcoming and accepted rapidly. Though thousands of displaced residents still live in temporary accommodation and the fallout from Fukushima nuclear power facility breakdown is still far from under control, Japan’s immediate response to its worst natural disaster in modern times is widely and properly seen as witness to the strength of Japan’s national character.

Yet Tohoku exposed disturbing flaws in Japan’s social and institutional structures that have raised deep questions about trust in national governance and continue to drive national self-reflection.

How could the nuclear accident and meltdown at Fukushima have happened amid assurances of the safety of Japan’s large nuclear energy program?

The Japanese nuclear energy industry’s pre-disaster regulation system was constricted by what has been called the Galápagos syndrome — that is, it was allowed to evolve independently of regulatory best practices elsewhere in the world. Japan’s Nuclear Safety Commission even dismissed International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) recommendations in 2008 ‘claiming the current nuclear regulation system had been functioning effectively to ensure safety at an outstanding level, even by international standards’. But, the old regulatory agencies — the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) and the Nuclear Safety Commission (NSC) — lacked teeth and their constitution was deeply conflicted. NISA was located within the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), involving a serious conflict of interest, as illustrated by METI’s plan, announced in 2010, to increase Japan’s energy self-sufficiency to 70 per cent by 2030, the vast bulk of this to be made up by nuclear. This would have represented a massive expansion above the roughly 30 per cent of Japan’s energy supplies, which were met by nuclear prior to 3/11. The utilities under regulation in turn were compromised by employing officials post first retirement (amakudari) in key jobs affecting regulatory compliance and the upgrading of standards. The risks in Japan’s nuclear program were under-estimated and a genuinely independent risk-assessment and regulatory agency was absent. As Yoichi Funabashi and Kei Kitazawa point out the ‘culture of secrecy and technical loftiness within the Japanese nuclear community…, allowing the industry to minimize the disclosure of detailed information about its operation, and to develop its own safety assurance practices’ did not measure up to global standards.

Japanese politics was dominated by energy, as Llewelyn Hughes points out in the wake of the disaster of 11 March 2011. The Japanese government’s decision ‘to shut-down all the remaining 48 nuclear units introduced real concerns of brownouts, previously unthinkable in Japan’s gold-plated power system. The parliament commissioned the first independent inquiry in Japan’s post war history, and gave it the task of finding out what happened, and how a similar event can be avoided’.

In 2012, a new regulatory agency, the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) was established under the umbrella of the Ministry of the Environment to replace NISA and NSC. It has adopted newer stricter safety standards. It has approved the re-opening of four nuclear power units (Kyushu Electric’s Sendai units No. 1 and 2 and Kansai Electric’s Takahama units No. 3 and 4). But there remains a major question of public trust in the Japanese government’s applying the lessons of Fukushima in its rush to re-open Japan’s closed nuclear power plants.

In this week’s lead essay, Tatsujiro Suzuki calls this loss of trust, which has not been sufficiently resolved even four years after the accident, ‘the most serious challenge that nuclear policymakers and the nuclear industry now face in Japan’. As Suzuki reports, just two weeks ago, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) issued a press release saying that the source of high radiation levels in one of its drains (leading into the sea) came from a puddle of rainwater that had accumulated on the rooftop of Unit 2 at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station… This particular incident was worse than usual because TEPCO was aware of the high level of radioactivity in the drain but failed to notify either the Nuclear Regulation Authority or the local government’. There is a climate of self-censorship in the media (that even impinged upon the one year anniversary address of the Emperor) that gives priority to not causing a panic among the public over research to establish how bad the Fukushima fallout is in all its knock-on effects and making information publicly accessible. There are also concerns about talk of bringing NRA under the direct control of the Cabinet Office, contrary to best regulatory practice and international advice, after a three-year review of the authority.

These are big stakes issues. As Simon Avenell also writes this week, the experts at Tokyo University reckon that there is a 70 per cent chance that a magnitude 7.0 or higher quake will hit Tokyo by 2016 and a 98 per cent chance it will hit in the next 30 years. So, in the face of these probable events, being confident about the management and regulation of Japan’s nuclear power facilities is no mere technical matter.

Peter Drysdale is Editor of the East Asia Forum.