When the Vietnam War ended there were those who genuinely hoped that a national unity government could be formed for the people who stayed. Early statements from senior leaders suggest such optimism was not ill-founded. But, by 1976, it became apparent that the new administration was more focused on building a socialist state than it was on working to heal the mental and physical scars of civil war.

The new Vietnamese government also took actions that harmed national reconciliation. It labelled the former Republic of Vietnam (RVN) regime an illegitimate, puppet regime (chinh phu nguy) and its servicemen and women ‘non-legitimate’ servicepersons (quan nguy). It established 30 April as the day when Vietnamese from the North ‘liberated’ the South. It confiscated the private properties of former RVN officials and businessmen, and divided it among party officials.

For the next 10 years, people associated with the former RVN regime were sent to re-education camps or forced to resettle in ‘new economic zones’. These actions undermined the rights, properties and freedom of the ordinary people, and did lasting damage to the cause of national reconciliation.

Throughout the 1970s and right through to the 1990s, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese chose to endure harrowing nights at sea on small, barely seaworthy boats in search of the freedom they had not found in their own homeland. Many died and the lucky refugees landed on islands in Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong and the Philippines.

Forty years on, reconciliation remains difficult despite the Vietnamese government’s efforts to encourage overseas Vietnamese to return ‘home’. The government first attempted to encourage repatriation more than a decade ago when the politburo issued Resolution 36, a resolution that emphasised the idea of ‘great unity’ (dai doan ket) of the Vietnamese people around the world.

Some overseas Vietnamese did return to invest in Vietnam and many other sent remittances. Statistics provided by Western Union show that in 2013 overseas Vietnamese sent US$11 billion to assist families and friends in Vietnam. Remittances are still necessary as ordinary Vietnamese in rural areas remain impoverished. Recognising the wealth of overseas Vietnamese, the Vietnamese government has relaxed visa programs and reformed land laws to allow foreigners to own property.

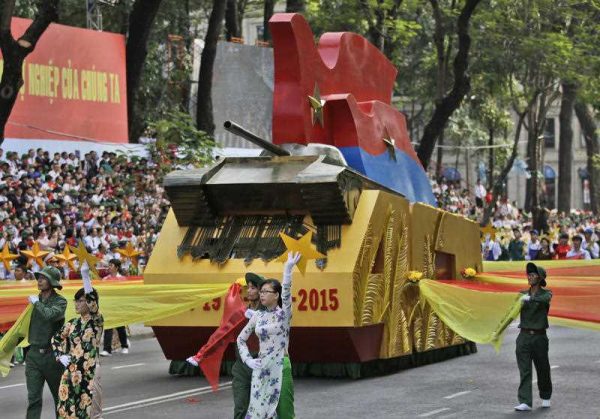

Despite these links, the overwhelming majority of Vietnamese living overseas remain opposed to communist rule and have not forgotten the past. As the Vietnamese government led celebrations on 30 April, overseas Vietnamese communities around the world held demonstrations to highlight Vietnam’s poor human rights record.

But talk of national reconciliation has re-emerged in 2015. This time, motivated by a desire of all Vietnamese to oppose Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, overseas Vietnamese communities — particularly from the United States, Canada, Europe and Australia — have worked together with civil society groups in Vietnam to exert pressure on China.

In an interview with the BBC, one prominent member of the overseas Vietnamese community, Professor Le Xuan Khoa, stated that animosity between Vietnamese cannot last and that national reconciliation will come in due course. Khoa made the point that there were people on both sides of the war who had strong nationalist spirit and he called for both sides to make compromises. Yet Khoa also emphasised that the government commitment to national reconciliation should be judged by actions and words that are more than symbolic. Khoa suggests that the government must reflect and re-assess its responsibility for the damage caused by its early policies.

Former president Nguyen Minh Triet has also spoken in favour of national reconciliation, talking of the need to mend differences for the sake of the motherland. He advocated for a formal reconciliation meeting between representatives of the two sides. He stated that the aim of the meeting should be to conduct a ‘grand amnesty’ (dai xa) to the participants. In making this proposal, Triet appears to echo the sentiments of former prime minister Vo Van Kiet who said in 1998, ‘if there are a million people who feel joy on the 30th April, there are also a million people who feel sad on this day’.

National reconciliation is likely to be successful if the government takes steps to heal the wounds of war suffered from both sides. But in a speech to mark 30 April celebration this year, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung referred to the mighty victory achieved over the ‘American imperialist and non-legitimate’ RVN army regimes. The spirit of triumphalism and lack of sensitivity to the other side of war has antagonised the overseas Vietnamese.

The discourse of national reconciliation showed the government has not grasped opportunities to unite the Vietnamese people. The government’s willingness to re-open the wounds of war has set back the cause of national reconciliation between it and the overseas Vietnamese communities. In the meantime, the ordinary people will hope that the next generation of leaders are able to free themselves from the battle-scars of war to make historic decisions that will advance national reconciliation and Vietnam’s national interest.

Toan Le is a Lecturer in the Department of Business Law and Taxation, Monash Business School, Monash University.

This post contains factual errors, improper context and thus, unrealistic conclusions:

. Although the war with the US and South Vietnam ended in 1975, Vietnam continued to be at war: 1st against China-instigated Khmer-Rouge in the south and direct Chinese cross-border invasion in the north. Relative peace only started late 1980’s and lasting impacts of peace, only physically and emotionally felt since early 1990’s. That hostility context and the American-led 1975-1994 total embargo, isolation are needed, to realistically evaluate everything else post-war.

. Furthermore, unlike the Germany merging of 6-times-larger population and 25-times-higher GDP West Germany, taking over the lesser half, population and economy size of north Vietnam was smaller than the conquered south. What was realistic expectations from this generation of guerrillas/administrators to do without no outside contribution, devastated landscapes, equally confused populates and amidst massive fleeing South’s best and brightest? Confiscation of

Thank you for your comment, Henry. The main idea of this article is to highlight the missed opportunities to establish national reconciliation and the costs of those missed opportunities. The aim of the article is to suggest some of the reasons that may explain why national reconciliation has eluded Vietnam, with the hope that one day Vietnam will be able to achieve national reconciliation and become a stronger nation.

The article did not seek to cast doubt on the difficulties encountered after civil war and war with the United States of America. However, those difficulties also highlight the need to establish policies that promote reconciliation and develop national unity of the Vietnamese people. Unfortunately, some of the policies implemented shortly after 1975 meant that many Vietnamese had to make difficult decisions to leave their homeland and many members of their family. The involvement of Vietnam in Cambodia was an important issue for the government, no doubt. However, a case could be made that the cause of national reconciliation was also important issue given the large number of Vietnamese were leaving the country over a period of more than twenty years, taking with them much needed talents to rebuild the country.

Regarding East and West Germany, the population was 16.11 million in East Germany and 63.25 million in West Germany at time of reunification (four times greater) in 1990.

http://www.populstat.info/Europe/germanec.htm

http://www.populstat.info/Europe/germanwc.htm

In 1974, North Vietnam had an estimated population of 23.77 million and South Vietnam’s population was estimated to be 19.58 million people.

http://www.populstat.info/Asia/vietnamc.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Vietnam

Given the similar population size and that the South Vietnam had a stronger economy, the establishment of reasonable policies on national reconciliation would have retained the best and brightest people to stay in their homeland and work with the new government to set Vietnam on the right path to economic development from 1975. Vietnam’s economic renovation from 1986 is an achievement that is recognised, but it also shows the significant cost of lost time and the cost of lost opportunities in not achieving national reconciliation earlier. The article recognised the wounds suffered from war by both sides is a big obstacle that will need to be overcome for true reconciliation to be achieved. The hope is that the next generation of leaders, born many years after the war, are able to make a new beginning, free from the scars and wounds of the past. Best regards, Toan