The poor quality of statistics on tribes is itself an indicator of their marginalisation. Poor statistics vitiate development planning and compound the development deficit of groups, like tribes, that need greater state support.

Even the most elementary statistics, such as census head count, are unreliable in the case of tribes, which — among other things — affects the quality of sample survey statistics. There are many reasons for this: the ambiguous definition of tribes; the politicisation and manipulation of census data; weak state institutions and insurgencies in tribal areas; development and conflict-induced displacement; the inaccessibility of tribal habitats; mobility necessitated by shifting cultivation and grazing; contest over the religious identity of tribes; and, in tribal-minority states, interference of non-tribal communities. Among these factors, ambiguous definitions and manipulation of census data are the most salient. The absence of objective criteria for identifying tribes leaves room for unintentional errors as well as manipulation.

‘Scheduled Tribe’ is an underspecified constitutional category in India. According to Article 366 (25) of the constitution, certain communities are ‘deemed under Article 342 to be Scheduled Tribes’. Article 342 stipulates that such communities are identified through a presidential order. The census mechanically follows the state-specific lists notified by the president. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs uses outdated criteria such as ‘primitive traits, distinctive culture, geographical isolation, shyness of contact with the community at large, and backwardness’ borrowed from the colonial administration to identify Scheduled Tribes.

It is not uncommon for a tribe to be recognised under different names in different states, while sub-groups of a tribe could be recognised as independent tribes within a state. And in the absence of a common national list of the Scheduled Tribes, the tribal status of communities varies across states, districts and even seasons.

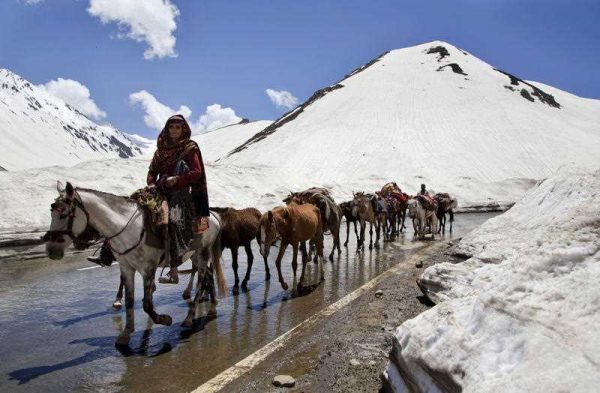

Until very recently, the Gonds — one of the largest tribes of Central India — were recognised as a Scheduled Tribe in Madhya Pradesh and as a Scheduled Caste in the neighbouring Uttar Pradesh. The Bakarwals — a nomadic tribe occupying Himalayan and Pir Panjal mountains — enjoy Scheduled Tribe status only in Jammu and Kashmir, and lose that status in winter if they visit neighbouring states in search of grazing grounds. In Assam, hill tribes are not treated as tribes in the plains and vice versa. Similar territorial restrictions apply in most tribal-minority states.

This leads to undercounting as tribal people have in the past been forced to abandon their home regions because of insurgencies, economic stagnation, ecological crisis and displacement due to forest and wildlife conservation, mining, and development projects. The problem of double-counting tribes is also not unheard of. At least until 2001, tribal people settled in urban Nagaland in Northeast India used to get enumerated both in the place of their present residence and in their ancestral village.

The ambiguous criteria used to identify tribes are conducive to manipulation. There are at least five ways in which tribal headcounts have been manipulated. Outside northeastern hill states and Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir, tribes are surrounded by non-tribal people on all sides. This makes it difficult to isolate tribes from non-tribal communities because the latter have an incentive to falsify their identity to claim benefits that are meant for tribes. Even a former Chief Minister of Chhattisgarh was accused of fraudulently acquiring tribal identity.

In Maharashtra, a non-tribal community claimed en masse to belong to a neighbouring tribe hoping that enumeration as a tribe would allow them to buy tribal land. This resulted in high growth of the tribe’s population and the statistical submergence of the original tribe.

Sometimes ghost tribes find mention in the census. In Nagaland, a residual tribal category that had an insignificant population share until 1991 suddenly emerged as the ninth largest community in 2001 before disappearing into oblivion in 2011.

In states such as Nagaland and Manipur, competition for legislative seats and welfare benefits resulted in an inflated headcount. Manipulation of the headcount also played a role in a case of forcible assimilation and co-option in Nagaland. A tribal community’s population registered an unusually high growth rate in the 1991 census when it was trying to assert its identity as distinct from a larger tribe. In the next census, its growth rate dropped by 90 per cent as the larger tribe tried to forcibly assimilate the community.

There have also been cases of selective co-option and erasure of tribal identities in states such as Assam and Uttar Pradesh, where the dominant non-tribal communities suppressed the linguistic, religious or ethnic identity of tribes.

Unfortunately, these errors have received insufficient attention. And flawed statistics continue to be used both by social scientists and policymakers, including the High Level Committee on Socio-Economic, Health and Educational Status of Tribal Communities. The task of harmonising state lists of Scheduled Tribes, for instance, has remained unattended for decades. Likewise, errors in Nagaland’s Census accumulated for three decades before attracting the government’s attention. Similar problems remain unaddressed in other states.

But tribes are often unable to contest government statistics because of their illiteracy, poor socioeconomic condition, and limited representation in the bureaucracy. The issue of poor data must be addressed if India is to pursue an informed policy for mitigating tribal disadvantage.

Vikas Kumar is Assistant Professor of Economics at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.

Ankush Agrawal is Assistant Professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi.

An earlier version of this article appeared here in Deccan Herald.