China’s ratification carries real weight because it has reached a turning point in its contribution and response to global climate change, as Fergus Green and Nicholas Stern point out in this week’s lead essay. China’s coal consumption fell in 2015 and ‘history will likely show that China’s coal use peaked in 2013-14’, they say. China appears to be on a trajectory towards lower carbon emissions.

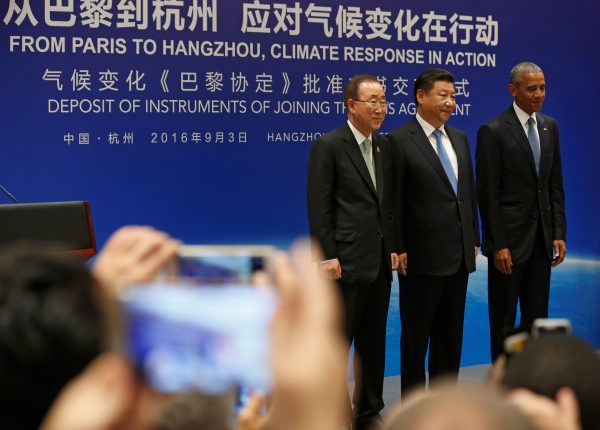

That the world’s two superpowers and largest emitters announced their ratification of the accord jointly just prior to the G20 summit, demonstrates that the United States and China can work effectively together despite their differences. It also breathes life into the G20 as the platform for global cooperation and coordination of global leadership. There couldn’t be a more important long term global issue than mitigating climate change. It was in the middle of the G20 held in Australia in November 2014 that the United States and China announced a major deal to curb greenhouse gas emissions and work together on the issue — to the embarrassment of its host, climate change sceptic, prime minister Tony Abbott.

The Paris agreement needs 55 countries accounting for at least 55 per cent of global emissions to ratify the agreement before the end of this year. China and the United States account for 38 per cent of global emissions and there could now be a surge in countries ratifying.

After failure to reach a global deal to cut emissions at Copenhagen in 2009, the world has shifted to a bottom-up approach. Asia Pacific countries recognise this approach as concerted unilateralism: where countries make voluntary commitments recognising the benefits and building the consensus at home with the non-binding agreement of countries implementing together to compound the benefits. APEC and the G20 are premised on similar modes of cooperation. This is a more sustainable way to implement international agreements than through reciprocal negotiation (often behind closed doors) that the public in participating countries is later asked to accept. The most important efforts at opening up East Asian economies came through such voluntary unilateral reforms — undertaken in concert the benefits were larger and the political economy commensurately easier. The approach is the same as that taken in the Australia–China Joint Economic Report.

A bottom-up approach means the level of ambition for each country’s commitment to cut emissions will vary. Leadership and peer pressure are important to achieve strong and ambitious commitments. The European Union is a leader on climate change, committing to cut emissions by at least 40 per cent by 2030 from 1990 levels. The United States has committed to cut emissions by 26 to 28 per cent by 2025 from 2005 levels. China has committed to reduce emissions intensity of its economy by 60 to 65 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, and to peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 with efforts for an earlier peak. Many analysts in China and outside expect that a peak in China’s emissions is closer than the 2030 target. Much of the global effort to avoid catastrophic climate change depends on China’s not following the carbon-intensive development path of the current advanced economies.

China is already on a less carbon-intensive growth path with emissions intensity declining by more 4 per cent per year for many years now, and seems likely reach its Paris agreement targets more than a decade ahead of schedule.

Green and Stern say that China’s greenhouse gas emissions will peak over the next decade. According to their assessment, ‘It is possible that China’s carbon dioxide emissions, which appear to have fallen in 2015, may continue to fall gradually’. The fall in China’s coal use and carbon dioxide emissions last year is not cyclical nor is it solely due to the slowdown in China’s GDP growth to rate to below 7 per cent. China’s energy intensity — the energy per unit of output for the economy — has been falling continuously and that fall has accelerated over the past two years. These are signs of early success in China’s transition to a new growth model driven increasingly by services instead of energy-intensive industrial activity.

China has good reason, as Jotzo has argued, to reduce its energy intensity and emissions. Air-quality and environmental pollution are major domestic political issues that affect social stability. The reductions in energy intensity and emissions have been achieved through a mix of market-based instruments and regulation. And while China’s carbon emissions trading scheme has received the majority of global attention, most of the action has been in the formation of new policies that have enabled China’s shift to a cleaner growth model.

China’s emissions trading scheme may not have played a major role yet but it is likely to do so in the future. Much more has to be done in China for it to reduce emissions and having the scheme in place to put a higher and higher price on carbon will mean it can do so efficiently. Countries that have tried and failed to introduce economy-wide prices on carbon emissions like the United States or countries that managed to do so but have since gone backwards, like Australia, may meet their Paris targets for cutting emissions, but are likely to be doing so in a more expensive way than with the widespread use of market-based mechanisms.

The tables have turned on countries that justified their own inaction by hiding behind China’s perceived inaction on climate change and the inability of the world’s major developed and developing countries to reach agreement in 2009. The excuses have run out and the price for many governments has been to lose the advantage of developing new technologies and making an early transition to a low-carbon growth model. Free-riding on the efforts of major powers could be costly for the free-riders with the world moving through the next industrial revolution.

China’s actions, Europe’s commitments and the US–China deal have changed the game. It’s the return of concerted unilateralism and countries able to ramp up existing commitments and deliver on those stand to benefit the most.

The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Ryan Manuel, Amy King and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.