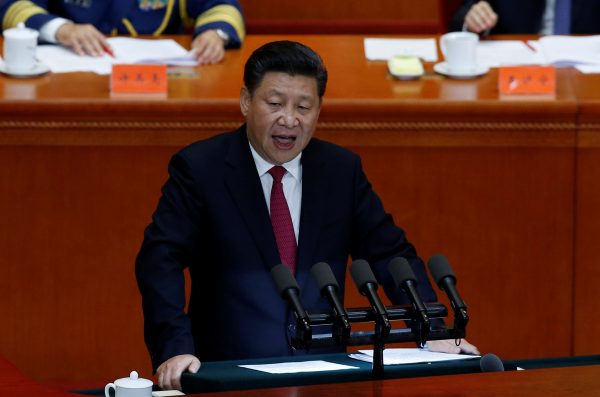

While President Xi Jinping’s second five-year term is assured, the 19th Party Congress in autumn this year will see one of the largest turnovers in China’s political leadership for many years.

This is the first of a series of assessments over the coming months of what this will mean for the Chinese party-state and its strategic direction.

Ironically, the questions that worry many in the United States and around the world about the Trump administration are not only to do with what impact the change in administration has had on US policy in the White House. They are also about the resilience of US constitutional conventions and institutions upon which reliable, democratic government has been built in the United States to the challenges that Trump and his confidantes in the White House present.

There is a widely-held and deep anxiety in democratic societies around the world that the Trump phenomenon presages abnormal change and a disturbing shift in US social and political norms. The United States no longer inspires the desire to emulate; it has also become, to put it simply, less like us.

This is not just a matter of conventional ideological difference over particular policy directions: the failed executive order to ban the entry of all travellers from seven nominated Muslim-majority states, building a wall along the border with Mexico or Trump’s assault on the global trading order through withdrawal from TPP and renegotiation of NAFTA. It’s about the loud, full frontal disrespect for the institutions of democracy — the judiciary; the press; constitutionally challenging conflicts of interest that surround the first family; and the inclination to favour the ways of thuggery in authoritarian states.

These are not only the anxieties of distant and foreign elites. Trump’s own political support base has collapsed around increased nervousness in the United States itself. A poll by the American Psychological Association reveals that two-thirds of those polled — or 66 per cent — said they were stressed over the future of the nation and nearly half — 49 per cent — said the outcome of the election was either a very significant or significant source of stress.

A more reassuring view of America’s new leadership and its effect on the strength of the state is that United States constitutional checks and balances are working well in reaction to an unorthodox, norm-breaking, law-indifferent President. Trump’s executive order on immigration was overturned in the courts and the judiciary has hit back on the attacks on judicial process. The press continues to do its job around the bluster.

In China, the political change set in train by President Xi when he assumed the Chinese presidency five years ago was directed towards strengthening a different kind of state. The 19th Party Congress in the northern autumn will mark an important step not only in the consolidation of Xi’s own political power but also in realising his ambition to fix the vulnerabilities of the party-state that he inherited.

In late 2012, when Xi became the general secretary of the Party, he was first among equals in the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), the highest decision-making organ of China’s party-state. By the end of last year, he had secured the endorsement of the party as the ‘core’ of its leadership, elevating his role as arbiter of important party and state affairs. Over the past four years, the journey towards centralisation of power has included launching a large-scale anti-corruption campaign, removing rival forces, strengthening internal political support and building new institutions that aim to reshape the party-state.

Beneath the surface of effective control, the Chinese party-state faced huge and growing economic, social and political challenges when Xi took over the reins of power. There was a sense of impending crisis in the minds of China’s ruling elite: rampant corruption was the most obvious symptom of the malaise in the political system. Bribery had permeated every corner of the party, the state and the military. It was also an unavoidable part of people’s daily life. It was commonplace for ordinary people to give bribes for receiving appropriate treatment when giving birth, having medical operations, or getting their children into good kindergartens and schools. There were price tags of some kind on virtually every public position. Promotion into government or military positions was no longer possible without paying money up the chain.

As Dong Dong Zhang writes in this week’s lead, for ‘most of Xi’s first term, the focus internally has been on overhauling the party-state: riding off corruption, centralising political power, imposing party self-discipline and applying strict codes of conduct for party leaders at all levels. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign has been central to achieving these objectives. When Xi said that “you need a strong body to be a good blacksmith” he meant that the party-state was weak, corruption was rife, the bureaucracy incompetent and the leadership fragmented. The party-state needed a thorough clean-up to avoid implosion like that which occurred in the former Soviet Union’.

As Zhang points out, the scale of the upcoming change in the CCP leadership and its importance can’t be overstated.

Does it mean anything for political reform?

‘Xi has rejected changes that would involve a separation of powers weakening CCP leadership but is committed to limiting power institutionally’, Zhang explains. ‘There’s no contemplation of an independent judiciary but the party leadership and party officials, no matter how high their position, will be subject to the law that is made by the Party. Xi’s establishment of the State Supervision Commission that places the use of power in the party-state under close institutional watch exemplifies this model. This distinguishes the Chinese political path from those that have been followed in the West or in the Soviet Union’.

The contradictions that are embedded in Xi’s resolution of his country’s ills should be plain for all to view in the travails that now test the great US constitutional democracy, where the triumph and integrity of an independent judiciary, the freedom of the press and the right to popular redress are required in full measure to ensure the responsible exercise of power.

Xi’s first steps on the rule of law may nonetheless be important. And what the 19th Congress means for market-based economic reform, widely perceived to have stalled in recent years, is one of the many questions about China’s political change to which we shall return.

The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Ryan Manuel, Amy King and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific.