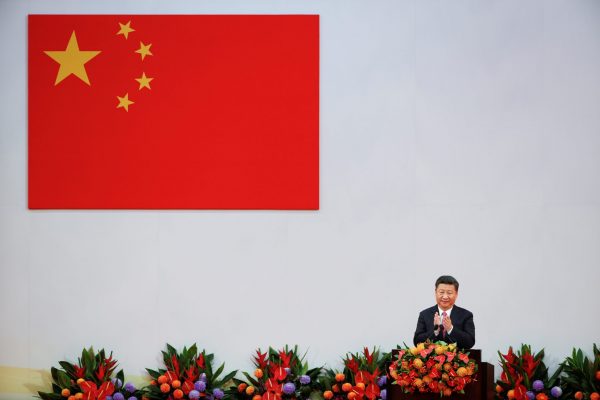

But while China has liberalised its economy and opened up trade, political liberalisation has been limited. Since President Xi Jinping took over in 2012, the country appears to be taking an even more authoritarian turn.

While advocating harmony as an essential Chinese value, the regime has been cracking down on human rights organisations, lawyers, feminists, religious groups, journalists and anyone else who ‘defies’ the party. Xi appears to be consolidating power in his own hands. Is China returning to the days of Mao Zedong? China’s leadership under Mao was highly personalistic and constituted the least institutionalised period of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Mao sought to root out all opposition and successfully built a cult of personality around himself.

Once Mao died, power became more dispersed. Leadership succession has also been managed effectively in China, with peaceful leadership turnover regularly taking place. The same is likely to happen when Xi’s tenure expires in 2022, though there are whispers that he will try to maintain another important senior post. The CCP has also concentrated on recruiting politicians with technical knowledge and educational background over personal loyalty and ideological commitment.

But despite institutional constraints, there remain fears that Xi’s government is becoming increasingly authoritarian with a new cultural revolution being entrenched. A cult of personality has formed around Xi, although he has stopped practices such as the state media referring to him as Uncle Xi.

Xi has also tightened his grip on power by going after his opponents in the higher ranks of the Communist Party. Over 100,000 party members are under investigation. He is rumoured to be even taking aim at former president Jiang Zemin. Available positions in the Politburo Standing Committee are mainly filled by Xi’s allies. He has purged the armed forces of potential opposition and appointed himself commander in chief of the military. Xi is demanding loyalty and working to weaken the power of elite family networks.

Reminiscent of Mao, Xi has created a sense of crisis in which the party seemingly needs to be vigilant. Recent crackdowns are taking place amid an environment of economic uncertainty. China’s economic growth is slowing down. The country is marred by a property bubble, ailing state owned enterprises, growing inequalities and overextended banks. Concerns of growing social unrest have caused the government to take strong measures.

One of these harsh measures includes cracking down on the press. Xi has personally visited the main Communist Party newspapers, the state news agency and the state television station to oblige editors and reporters to make loyalty pledges to the Communist Party and its leadership. Xi’s regime has also exercised heightened control over what Chinese citizens can express on the internet and what information they can access.

The regime has gone as far as to use extra-judicial detention centres to suppress human rights activists. Civil society groups have been shut down if they pose a ‘threat’ to the regime, while the new Foreign NGO and Domestic Charity Laws appear to be designed to interpret the word ‘threat’ very liberally. Labour groups are also subject to harassment and detention. There has been a clampdown on religious organisations, with Muslim, Jewish and Christian communities all at risk.

As China is the second biggest economy in the world and has trade links with almost every country, it is unlikely that the West will do anything to temper Xi’s grip on power or nudge China towards democracy. Despite the growing protectionist slant of the United States, US–China trade still totals over US$600 billion. In May 2017, the two sides signed a major trade deal. What is more, as the United States has become more isolated under President Donald Trump, China and the European Union have engaged under a common vision of multilateralism.

Crackdowns often take place in a context of vulnerability. Xi has concerns not only about the country’s economic future but also his own future as head of the party. But while Xi is escalating repression, comparisons to Mao are stretched.

The current Chinese government has a much greater interest in popular opinion than Mao ever did. Xi’s government does not exercise total control over information, as was the case in the Mao era. The Xi government is also not an opponent of science. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao tried to create a homogenous culture that eschewed intellectuals and evidence that contradicted him. Mao’s dogmatism led to an economic agenda that was so flawed that it was responsible for the biggest manmade disaster in history.

There remain strong institutional constraints on Xi’s power in the constitution and the practices of the party–state. Xi may be tightening his grip on power in China but he is unlikely to drive the country into the despairs of the past.

Natasha Ezrow is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Government, the University of Essex.

To be honest, if China indeed “democratises just as many of the Eastern Bloc nations have done”, it will be just as crappy and hopeless as, if not more so than (due to the sheer size of China), those Eastern Bloc nations today instead of being the second most powerful nation on earth.

So in the end, will Xi become just like Mao in terms of political power? Who cares. What Chinese care about is if China will continue to prosper and if people’s lives will continue to improve. As Deng Xiaoping once said, black cat or white cat, the one that can catch mouse is the good cat.

A bit of fear mongering isn’t it? While he is at it, why not compare with Stalin as well?