But does vote buying actually help politicians win? And if not, why do they still do it?

A post-election survey of voters found that vote buying has discernible effects on ‘only’ 10.2 per cent of the Indonesian electorate. This seemingly low impact on voting decisions is largely due to the fact that most candidates and brokers are targeting the wrong voters. They intend to target voters who are loyal to their candidate (with the intention of boosting turnout), but given the low number of partisan voters, successful vote buying mostly happens among swing voters who do not then vote for the broker’s candidate.

Vote buying is also vulnerable to rent-seeking behaviour from brokers and voters. Brokers tend to exaggerate the number of candidates’ base voters — even deceiving their candidates on this issue — so that they can engage in predation. But many of the people who are recruited by brokers are not then loyal to the candidate they have promised to support.

Indonesia’s open-list proportional voting system plays a crucial role in explaining the ubiquity of vote buying. Under this system, candidates must compete against their party peers for personal votes, and they only need to win a small slice of the votes to defeat their internal rivals. The average winning margin by which the victorious candidates edged out rival candidates from their party’s list in Indonesia’s 2014 legislative election was only 1.65 per cent.

This means that despite vote buying’s inefficiency and small effects, in close contests such as in Indonesia vote buying can still make a difference to a candidate’s odds of victory. Even if offers of money influence the vote choice of ‘only’ 10 per cent of voters, this figure is high enough for many candidates to clinch a win.

Vote buying was almost unheard of in Indonesia’s first free election after the fall of Suharto in 1999 when Indonesia adopted a fully closed-list system (where voters can only vote for parties and do not have power over the order in which party candidates are elected). In such an electoral setting, candidates have little incentive to engage in vote buying approaches because the competition primarily takes place between parties and candidates are more likely to rely on party reputation.

Vote buying in Indonesia was still not widespread in 2004. At that time, Indonesia introduced a semi-open system, where people for the first time could express their preference for a particular candidate. But because the 2004 election law instituted only a semi-preferential system, higher-ranked candidates on a party list had a higher chances of being elected. As a result, patronage distribution was still limited in the 2004 election.

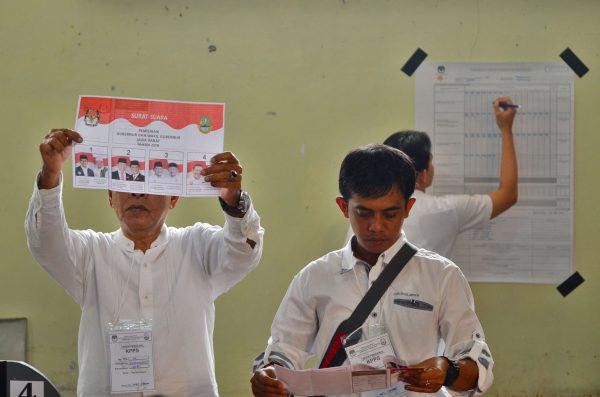

The picture changed dramatically with the introduction of a fully open-list system in 2009. Just a few months before the 2009 election, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court annulled the previous system and decided that seats won by a party had to be given to candidates from that party who obtained the most individual votes — regardless of their positions on the party list. Vote buying started to become a common strategy among candidates to pursue personal votes.

But candidates did not have sufficient time to completely change their strategies to a more personal campaign approach before the 2009 election: only 11.2 per cent of respondents admitted to being targeted for vote buying in that election.

By 2014, candidates were familiar with the fully open-list system and launched their patronage-based approaches to seek personal votes. The incidence of vote buying in 2014 tripled in comparison to 2009.

Indonesia’s open-list proportional system clearly shapes the supply-side of vote buying. The institutional remedy is to return to a more party-centred electoral system by re-applying closed-list proportional representation.

Timor-Leste is a good example of how a closed-list system discourages politicians from adopting vote-buying strategies. Although East Timorese voters’ willingness to engage in vote buying was high during the 2017 election, little evidence of vote buying has been found. Only 4 per cent of East Timorese report having individually been the target of such handouts.

A closed-list system is not perfect either. When Indonesia adopted a closed-list system in 1999, there were numerous reports of wealthy candidates purchasing winnable slots on party lists by bribing party leaders. But even accounting for this weakness, the diminished incentive for widespread vote buying in a closed-list system make it preferable to the easily exploitable status quo.

Burhanuddin Muhtadi is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Political Science, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta.