Following two years of confrontation after Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in 2012, Chinese–Japanese relations have in fact been on a steady upwards trajectory. In a delicate and uncertain regional geopolitical context marked by China’s rise, US retrenchment and dangerous flashpoints on the Korean Peninsula and in the South China Sea, this Chinese–Japanese rapprochement is a positive anomaly. Despite their poor reputation, Xi and Abe have contributed to it greatly.

Xi Jinping is determined to lead his country to a ‘great rejuvenation’ in the coming decades. When it comes to the defence of China’s ‘core interests’, he has shown no compunction in using his power to orchestrate an assertive response to the behaviour of other states that he considers provocative, acting first to strengthen China’s hand before considering a diplomatic solution.

Xi seeks to present China as a peaceful and benevolent great power willing to cooperate with any country prepared to put differences aside. He is keen to play the role of friendly neighbour while at the same time defending his country’s honour and interests. Case in point: his shift in attitude towards Japan. Despite persisting tensions, a shift in attitude in 2014 opened the way for a careful but steady rapprochement that could culminate later this year with an official visit from Shinzo Abe.

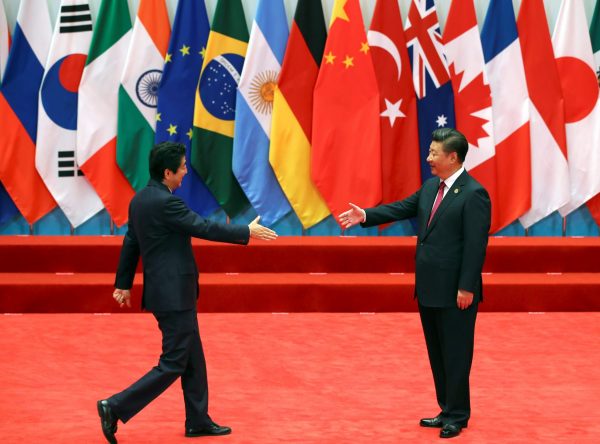

Considering the sensitivity of relations with Japan, Xi’s firm grip on all levels of power continues to push the Chinese rapprochement forward. Xi has now met Abe multiple times and has repeatedly expressed his willingness to forge better relations. This sense of direction at the top is what enables progress on managing security tensions and developing economic cooperation.

Abe is often portrayed as an anti-China militarist hoping to ‘make Japan great again’. This image took roots during his first stint in power in 2006–07. At the beginning of his second mandate, Abe apologised for his excessive zeal, pledging to be more cool-headed this time around. But his rhetoric on ‘taking back Japan’, his affinity for the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, his support for expanding the roles of the Japan Self-Defense Forces and his plan to amend Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution are all sources of concern for Beijing.

Political rhetoric aside, Abe’s foreign policy has been measured when it comes to China. The flare-up of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute in 2012 may have helped him return to power, but his administration has been restrained in its response to regular dispatches of Chinese vessels to the waters that surround the islands. Abe has certainly remained unequivocal in defending Japan’s sovereignty, but his administration has taken no escalatory measures. Abe has repeatedly argued that territorial issues should not derail a relationship vital to regional and global stability.

Since 2014, Abe has underlined his desire to improve the relationship and has offered to cooperate under certain conditions with Xi’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This offer was welcomed by China and could be an important driver for continued collaboration going forward.

Both leaders have clear incentives to cooperate, including mutually beneficial economic ties and the need to prevent further escalation around the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. Managing a difficult relationship projects an image of China and Japan as responsible states, the former a rising power capable of putting old grudges aside and the latter an established power willing to welcome its neighbour onto the international stage despite security concerns.

For Xi, stabilising relations with Japan is particularly important in the context of a Chinese shift in focus from pressing for its territorial claims to engaging its neighbourhood economically through the BRI. For Abe, finding a modus vivendi with China is equally urgent as he seeks to offset China’s growing military and economic might.

Whatever nationalist tendencies they may have, Xi and Abe have demonstrated pragmatism to go beyond conflict and instead make progress on their common interests. The strength of their domestic leaderships are an important guarantee that this momentum will be maintained.

Future stability is not guaranteed. The structural drivers of tension and the potential flashpoints in the East China Sea will not disappear. The two countries lack a mutually agreeable framework to govern their overall relationship. Unforeseen incidents or rash behaviour could bring about a return to confrontation. It seems that right now Chinese–Japanese relations are as good as one could hope them to be.

The establishment of a productive relationship between Xi and Abe is no substitute for rebuilding deep mutual trust between the two countries. It may be overly optimistic to expect the two leaders to make significant progress on the road to true reconciliation in the near future. But if the current trend is maintained, it may pave the way for more serious attempts at tackling the contentious issues that continue to strain China–Japan relations.

Andrea Fischetti is a MEXT scholar at the University of Tokyo and the Asia Pacific Initiative.

Antoine Roth is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School for Law and Politics, University of Tokyo.

So far Xi has avoided bringing up the issue of the Comfort Women. And Abe has not demanded that Chinese boats and planes stop entering the area around the disputed islands.

It will be very interesting to see how Xi, as well as other Asian leaders, will respond if/when Abe moves to amend Article 9 of the Japanese constitution. And how much Xi can influence Kim of N Korea in the ongoing issues with the Korean peninsula.

Many complex uncertainties remain, any one of which let alone in combination could unsettle the situation.