A year ago, it was difficult to imagine any credible political opposition rising to the incessant march of the BJP, which was winning one state after another under the Narendra Modi–Amit Shah duopoly. Today the situation is markedly different. The INC emerged victorious in the November elections, winning in three out of the four states — two of which were BJP governed states. Regional parties too formed pre-poll alliances to pose a credible threat to the BJP in states like Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka.

Such trends shed light on the mindset of the average Indian voter and the factors that may influence their decision in the upcoming national elections.

The state election results speak to the instinctive and democratic nature of the average Indian voter. They suggest that voters today would not hesitate to vote the ruling regime out if they felt it had done little over its four-year term to improve opportunities for economic mobility, lower inflation, increase social protection measures or boost economic security.

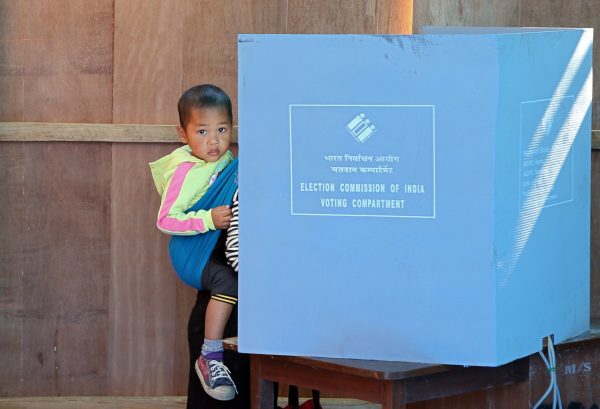

As a result of greater political awareness and discourse (thanks to social media and India’s mobile data revolution), more people are now voting and even the gender gap in voter turnouts has significantly reduced.

The average voter also seems less influenced by the wave of identity-based politics that was earlier (and is still) used to mobilise votes across groups. Parties may no longer see polarisation of political measures along religious, caste-based identity lines as a sustainable strategy to influence voter preferences.

At the same time, and more importantly, these trends indicate that the main political opposition must offer something that sets it apart from the BJP in its 2019 campaign. State election results, while indicative of the general mood of the public, may only partially shape voting behaviour in the upcoming general elections.

National elections require parties to present a long-term national vision and a coherent economic and political agenda. An alternative economic vision is critical to resolve the current state of the Indian economy, shaped by the catastrophic impact of centralised economic policymaking.

The draconian monetary experiment of demonetisation, followed by the centralised, ad-hoc implementation of the goods and services tax punctured the racing wheels of the Indian economy under the BJP. Poor handling of the public sector banking crisis (with rising non-performing assets and bad debt), a persistent decline in domestic investment levels and a protracted conflict with the central bank are only making matters worse.

In designing an alternative economic vision, there are at least four areas that India’s political parties need to work on to gain voters’ support.

The first involves improving the economic conditions of the agricultural class, which comprises more than 40 per cent of the workforce. Farmers need to be seen as micro-entrepreneurs who require better market access for their products and not higher minimum support prices or loan waivers. Promising a package of reforms that address the 5Ps (price, product, position, protection and profitability) and involve greater participation of the farming community in the drafting process could be one step in this direction.

The second major area in need of reform is access to basic social services, including education, healthcare, drinking water and sanitation, financial credit and legal aid. Regional parties in states with better performance in this regard can contribute to the design of national level strategies and advise on what steps may allow more affordable access to social services, particularly in semi-urban and rural areas.

The third aspect entails working towards gender empowerment across occupational classes while increasing social, political and economic opportunities for women. Evidence from previous and recent elections suggest that in times of stiff electoral competition, political parties in India tend to field fewer female than male candidates, citing women as ‘weaker’ options. The 2019 general elections must see greater party support for female candidates and more work towards addressing pervasive gender inequality.

The fourth is concerned with ensuring maximum social protection to minority groups across the country. In 2018 India saw the highest reported rate of religious hate crime in over a decade. A cohesive vision for social protection is needed that allows religious, ethnic or tribal minority groups greater representation and participatory autonomy in decisions that affect their social and economic well-being. Police and labour law reform are also key to this context, ensuring better social protection among minorities and other vulnerable groups.

As of now, an alternative vision for the Indian welfare state remains in contention. The political opposition (including regional parties) is yet to present a plan of action to address the above areas or a prescriptive set of long-run economic policy measures. With the INC calling for unconditional farm loan waivers, it would not be surprising if the BJP offers a huge incentive package for farmers (including a universal basic income-style cash transfer scheme) before its last budget to woo more votes from dissenting farmers.

Entering 2019 with elections around the corner, the average Indian voter appears to be uncertain about who they should lend their trust.

Deepanshu Mohan is Assistant Professor of Economics and the Director of the Centre for New Economics Studies at the Jindal School of International Affairs, OP Jindal Global University.