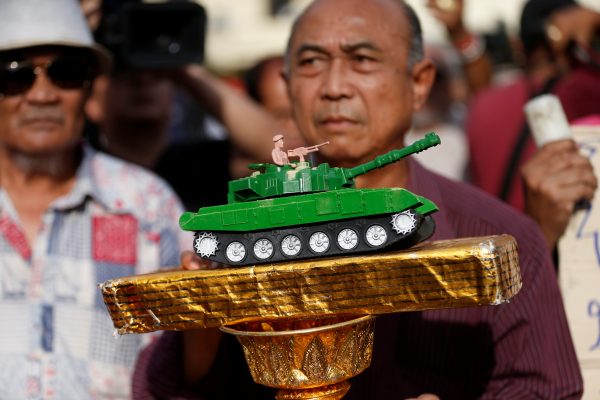

Early in the year, Prayuth found himself facing a series of protests. Protestors defied the ban on political activities to protest both specific policies, such as a coal-fired power plant in Songkhla and a housing scheme in Chiang Mai, and to demand elections be held in November as previously promised. The protests proved problematic for Prayuth. Suppression would damage his popularity while concessions would simply encourage more protests.

Prayuth took a mixed approach, making concessions to policy-orientated protests — the coal plant and the housing scheme were indefinitely delayed — while seeking to suppress pro-democracy protests. Yet attempts to crack down on pro-democracy protests proved more problematic than expected. In one instance the courts ordered the police to let a protest march go ahead, and in general, the courts delayed judicial actions and treated protestors with considerable leniency. While political parties could not support protests due to the ban on their activities, the press expressed considerable sympathy and support.

Consequently, Prayuth sought to shore up his popular support in two ways. First, he initiated the process of political party registration in early March. The emergence of a range of new parties — some in support of the regime, some in opposition — gave the appearance of progress towards democratic elections, even while the ban on political activities formally remained in place. Second, government leaders travelled the country, holding meetings and promising funding for various projects. For example in May, Newin Chidchob (the politician who abandoned former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra to join a military-brokered coalition in 2008) assembled a crowd of 30,000 people in Buriram to cheer on Prayuth as he promised greater state funding for the province.

Beyond this populist-style campaigning, Prayuth achieved considerable success in recruiting powerful faction leaders from established parties to join the pro-government party. The effectiveness in recruiting former members of parliament from other parties can be attributed, in part, to a desire among politicians to maximise their opportunities to serve in the cabinet — which many calculate is more likely if they join a pro-government party — and in part to pressure from the military on some influential politicians.

Similarly, politicians have increasingly switched their allegiance to the pro-government Phalang Pracharat party in order to secure their livelihoods. Political parties gain financial and electoral advantages from holding political offices. Yet political parties have now been out of office for nearly five years. Only the Phalang Pracharat Party has both the funding and access to office to provide generous support to its candidates. However enthusiastically or reluctantly, many former members from other parties have consequently joined Phalang Pracharat.

Throughout 2018, Prayuth delayed confirmation of the election date, perhaps to justify leaving the ban on political party activities in place. In November, just prior to lifting the ban, the government announced a large package of benefits for the poor (including 500 baht in cash, mobile phone SIM cards with free internet and up to 330 baht paid on utility bills each month through to September 2019). Additional benefits were provided to the elderly, to retired civil servants and to low-income home-buyers. The Election Commission sided with the government when political parties appealed on the basis that the policies were meant to influence the election.

The competing parties can roughly be divided into three groups. First are the pro-government parties led primarily by Phalang Pracharat, with about 100 former members of parliament gathered from other parties. Second are Pheu Thai and its associated Thai Raksa Chat party. The latter was created both to ensure survival if the main party is dissolved and to maximise party list seats under a convoluted electoral system designed by the junta to maximise seats for medium-size parties. Third is the Democrat Party, with former prime minister Abhisit Vejjajiva maintaining his leadership position.

The return of Prayuth seems the most likely outcome under the current system, where 250 junta-appointed senators join members of parliament in voting for the prime minister. Yet to govern, he will still need to form a majority government in the House of Representatives — a much greater challenge. While Pheu Thai has demonstrated a remarkable ability to maintain seats in the face of past defections, repeating that success will be challenging with less financial and institutional support. The Democrat Party’s best hope is to win enough seats to be kingmaker, where its support is necessary to both Pheu Thai or Phalang Pracharat in forming a coalition.

If Prayuth does return, especially in such a coalition, he will need to employ a very different set of skills to those on which his rule has depended over the past four-and-a-half years. For the first time, he will face an opposition in parliament and lead a party whose members have little in common besides a desire for office. In such an environment, Prayuth may well find a greater need for consultation and participation than he anticipates, as well as other skills he has yet to demonstrate.

James Ockey is Associate Professor at the School of Language, Social and Political Sciences, University of Canterbury.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on 2018 in review and the year ahead.