After the financial crisis in 1997 the grouping created an ASEAN Vision 2020 strategy to marshal efforts to deepen cooperation and build a regional community. It has since launched many plans and blueprints, and made commitments to and launched an ASEAN Economic Community in 2015.

Southeast Asia is diverse and its regional institutions pale in comparison to Europe or many other parts of the world. Its members don’t always honour their non-binding commitments across a range of economic, social and political areas. And to some ASEAN appears perennially close to crisis or at risk of becoming irrelevant or fractured.

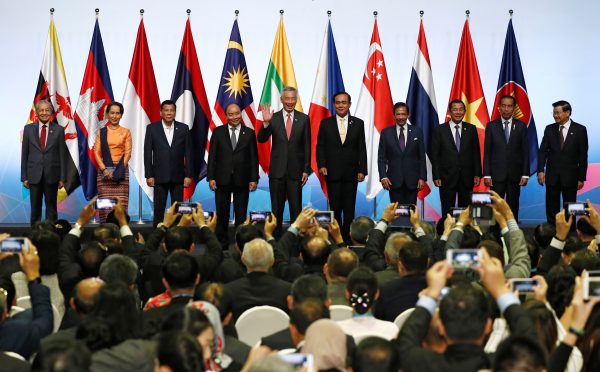

But ASEAN has made huge progress. It is the centre of East Asian value chains that bind the region together and lock China, Japan and others into a highly economically interdependent region. And because China and Japan don’t get along, much of their cooperation is done through ASEAN processes like the ASEAN+3 grouping (adding China, Japan and South Korea) and the ASEAN+6 grouping (with Australia, India and New Zealand in addition to the Northeast Asian three). They are also at the centre of the East Asia Summit that includes dialogues with these six countries and the United States and Russia.

ASEAN may sometimes fall short of its own benchmarks but it is vital to stability, peace and prosperity in Southeast Asia, as well as in driving the strategies behind broader regional cooperation.

The challenges that now face ASEAN are another test for the grouping. As Ponciano Intal Jr explains in this week’s lead piece, ‘the realignment of great power relations in the Asia Pacific is causing great geopolitical uncertainty. The Digital Revolution and Fourth Industrial Revolution are expected to accelerate, generating regional unease about its impact on lower end employment’.

And the multilateral fabric on which ASEAN’s economic interactions depend, both within its membership and with the rest of the world, is under threat from the rise of protectionism and the attack on the core principles of the global trade and economic regime. The rules-based multilateral trade regime and economic order is vital to ASEAN’s prosperity and the threat to that regime is a threat to economic and political security in Southeast Asia.

In the lead up to 2020, ASEAN has begun the think work for ASEAN Vision 2040. The next two decades will see history’s largest increase of middle and upper-middle classes in the India–ASEAN–China corridor, dubbed the ‘golden arc of opportunity’, but Intal warns it’s not automatic that ASEAN will be at the fulcrum of that revolution.

The first priority for ASEAN is to continue its economic integration and community building. This will require reforming and strengthening ASEAN institutions, being able to project ASEAN interests more effectively on the global stage and, most importantly, prosecuting economic reforms in each country.

ASEAN’s neighbours are major economies and securing an ambitious Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement with the ASEAN+6 will be a platform for deepening those relations. At the heart of that agreement will be an economic cooperation agenda that, beyond capacity building, provides a mechanism for deepening economic and political cooperation.

Responses to external initiatives will be important as well. How ASEAN responds to the Belt and Road Initiative from China, the putative Quadrilateral Security Dialogue from Australia, India, Japan and the United States and the reframing by some of the Asia Pacific region into the Indo-Pacific, will matter for ASEAN’s future.

Thus far there has been no collective or coherent response to any of those external plays to shape the region. The Belt and Road Initiative can bring much needed infrastructure that can improve connectivity within ASEAN and with its neighbours, but without an ASEAN plan the priorities will be set by China and infrastructure financing will likely go to where regulations and governance are weakest, increasing costs and risks for all.

The Quad, which is made up of four democratic countries, cuts across ASEAN geographically and its inclusiveness. Systems of government vary significantly in Southeast Asia and all share deep economic integration with China — the target of containment by the Quad. The idea of the Indo-Pacific will be difficult for ASEAN to swallow in some of its conceptions and ASEAN’s response to reframe its broader regional dealings won’t be an easy fit with the idea. Even the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), or TPP-11, challenges ASEAN cohesion because not all are members, nor likely to be.

The major powers that surround ASEAN pay lip service to the importance of ASEAN centrality and cohesion. But their initiatives present challenges to ASEAN. And the tectonic shifts in the structure of economic and political power around Southeast Asia will mean a turbulent time ahead. ASEAN will need to be more strategically proactive to continue to provide stability for its people as well as in broader regional and global affairs.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.