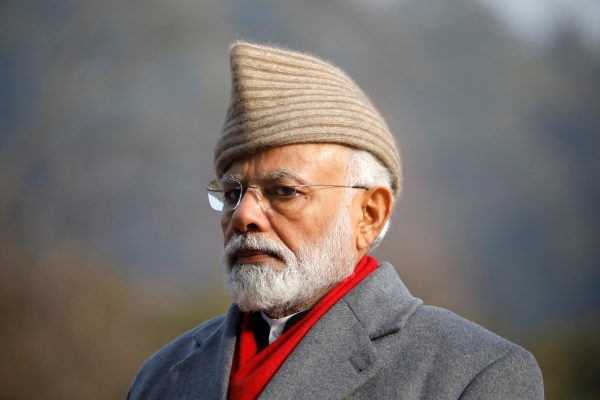

Modi’s campaign continues to promise to bring his model of development, crafted during his time as chief minister of Gujarat, to the rest of India (glossing past the reality that other states have outperformed Gujarat). Modi’s model promises to protect Hindu values and to create a business-friendly environment. He criticises Gandhi for inheriting his position and the INC as a dynasty without substance; Gandhi’s father, grandmother and great-grandfather were all former prime ministers.

In contrast to Modi’s glitz, Gandhi often comes across as inconsistent, lacklustre and reserved. He has begun to come out of his shell since taking over as INC party president from his mother, Sonia Gandhi, in December 2017 but has much brushing up of his image still to do. He now seeks to distinguish himself by showing his concern for India’s poor and criticises Modi as a public relations junkie who doesn’t deliver when the camera turns away.

Beyond the political histrionics, how does Modi’s five years as prime minister actually stack up?

As Raghbendra Jha points out, when comparing economic statistics between the last year of the previous INC government under Manmohan Singh and the most recent figures under Modi there have been improvements. ‘Real GDP growth is estimated [to have grown] at 7.2 per cent over 2017–18’, up from 6.39 per cent in 2013–14. ‘CPI inflation is estimated to have dropped from 9.6 per cent over 2013–14 to 4.7 per cent over 2017–18… and state fiscal deficits have come down from 6.7 per cent of GDP over 2013–14 to 5.9 per cent over 2018–19’. These are figures many countries would envy.

Yet those figures tell a rosier story than the reality. As Robin Jeffrey explains in our lead article this week, Modi’s many initiatives have achieved mixed results and face implementation challenges. GDP growth ‘has not translated into the millions of jobs that are needed for the 65 per cent of the population (850 million people) under the age of 35’ so that rising unemployment risks squandering India’s demographic dividend. The new GST tax system is expected to help improve and increase tax collection and better tax those with wealth, but it is over-complex and ‘is said to be a nightmare for small businesses’.

The sudden decision to demonetise 500 and 1000 rupee notes in November 2016, aimed at stopping black money escaping the tax net, caused considerable harm to business, agriculture, jobs and GDP growth, but the policy’s implementation mess was brushed aside. Modi’s ambitious Clean India campaign, a ‘top-down program to transform public sanitation…has built tens of millions of toilets [and] instituted cleanliness rankings’ but suffers from ‘failures of follow-up and maintenance’. And the new ‘national health insurance scheme for the poorest people, announced a year ago, seems under-funded and more show than substance’.

After Modi’s overwhelming 2014 election victory — the first government to form a majority without coalition partners for nearly 30 years — his mixed record gave Gandhi and the INC an opportunity to gradually claw their way back to political relevance. This was evidenced most clearly in November 2018 state elections where the INC took power in three key states in Modi’s Hindu heartland. Opinion polls in January suggested election results that would maintain the BJP as the biggest party, but that it would need support from a coalition beyond its normal National Democratic Alliance partners.

The contest has now been transformed by recent hostilities between India and Pakistan over the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir. As Ayesha Ray explains, after a number of tit-for-tat exchanges including the killing of 40 Indian police force soldiers ‘neither side is willing to set aside their country’s interests in favour of improving the lives of the people of Kashmir’. Thus, ‘a negotiated settlement that genuinely addresses the interests of all stakeholders seems unlikely at this moment or in the foreseeable future’.

The ongoing tensions with Pakistan have given Modi an opportunity to unsheathe his nationalist sword. ‘The BJP will aim to use these emotions in election campaigning’, warns Jeffrey. Modi has form in this space. He is a life-long activist for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) an umbrella of Hindu nationalist organisations. In 2002, while chief minister of Gujarat, he turned a blind eye to an anti-Muslim pogrom that saw over 1000 dead, something which saw him denied a visa to the United States until after he ascended to India’s top job.

Modi’s rhetoric as prime minister has also promoted an atmosphere of Hindu majoritarianism, ‘an aggressive one-size-fits-all version of Hinduism and of India’. Social media such as WhatsApp have been used to push fake news of hateful messages. This has resulted in ‘sporadic attacks on Muslim “cow killers” and “beef eaters”, and intimidation of despised “secularists” and lower castes who don’t toe the line’.

Modi has been ‘publicly bragging that [India’s military] surgical strikes deterred further terrorism from Pakistan’, explain Frank O’Donnell and Debalina Ghoshal, though they apparently hit no strategic targets. While such nationalist rhetoric may help Modi shore up his election base, it is a dangerous game. ‘[A]nother significant terrorist attack would naturally present Modi with an unwelcome choice’: launch a larger retaliatory attack and risk ‘an escalation spiral with nuclear-armed Pakistan’ or ‘adopt diplomatic and other non-military responses that would amount to a loss of face on his part’. It is critical that India and Pakistan ‘identify off-ramps to the crisis’ in order to de-escalate tensions and cut the cycle. Modi would be wise to remember that no election victory is worth risking going to nuclear war.

As Jeffrey concludes, Modi would do well to accommodate India’s ‘immense diversity — 1,300 million people, 29 states, 23 official languages, 11 different scripts and home to members of all the world’s great religions’ — and to find new modes of cooperation that will be necessary in the likely event of a hung parliament.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.