Taking a contrarian view on this topic provides significant insight into the shortcomings of current South Korean foreign policy. This has recently come to the fore in South Korea’s attempts to address issues relating to North Korea.

In 2017–18, South Korea understandably pursued crisis diplomacy as the threat of immediate conflict increased with inflammatory US and North Korean rhetoric. This required high-level decision-making, close coordination between partners and allies, clear initial signalling, limited and achievable goals, and a willingness to compromise. South Korea’s crisis diplomacy was highly successful and managed to rein in US and North Korean excesses and reduce the risk of miscalculation and conflict.

But the effectiveness of crisis diplomacy is limited by time and does not provide tools to transform the root causes of tension.

Assuming a behaviour-based definition of middle power, South Korea’s crisis diplomacy should have immediately been followed by characteristic middle power diplomacy. As soon as security tensions reduce, a middle power initiative should be launched.

South Korea could have actively increased its negotiating leverage by working with other middle powers (coalition building) and pursued innovative, creative diplomatic instruments to secure South Korean objectives (activist diplomacy). It could have also utilised tools that provide middle powers with comparative advantage (niche diplomacy) and promoted its efforts as ‘the right thing to do’ for a responsible member of the international community (good international citizenship).

Without middle power diplomacy, South Korea has effectively allowed its foreign policy to be steered by the vagaries of North Korea and the United States — one apparently incompetent and unpredictable, the other impenetrable and incorrigible (in fact these criticisms are interchangeable). South Korea has no negotiating leverage vis-a-vis the two actors, and no capacity to constrain their actions. It has allowed its agency to be subsumed by them.

Western media coverage of the Singapore and Hanoi summits highlight this fact. For most viewers, the entire issue concerned the United States, North Korea, and host Vietnam. South Korea hardly rated a mention.

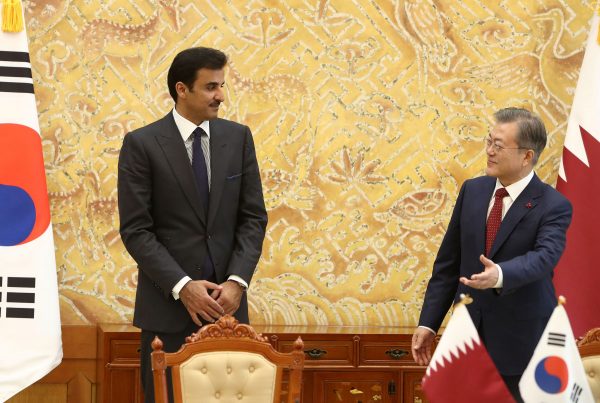

South Korea now has no control over the structure of future agreements, institutions, or instruments to be used. This means that current diplomatic endeavours based on high-level summitry leave it little room for flexibility. Any successes can unravel with a change of government in two (US President Donald Trump), three (South Korean President Moon Jae-in), or six (second-term Trump) years.

North Korea could potentially secure its medium-term aims to reduce constraints on its economic activity without any impact on its long-term aim to maintain a credible deterrent to external intervention. Failures can be blamed on changed policies in partner states and the entire game can be played again later.

There are several reasons that could explain why South Korea is unable to use middle power diplomacy to address issues relating to North Korea.

Foreign policy formulation in South Korea is strictly hierarchical. Ideas and initiatives start with presidential advisors and pass downwards to be implemented by the foreign ministry. Rarely are core initiatives formed within the ministry. This means that if the small coterie of presidential foreign policy advisors is cognisant of middle power diplomacy, then ideas will flow. If their interests lie in other areas, middle power diplomacy will be absent.

Organisational culture within the foreign ministry is also highly conservative, hierarchical, and risk averse — new, creative and innovative ideas are less readily accepted. There is less willingness to open up and interact with non-traditional foreign policy actors.

The concept and understanding of how middle power diplomacy works is still relatively new in South Korea despite the popularity of the term. Realism remains the most dominant paradigm to understand international relations and major power competition remains the most popular subject. Rarely do schools of international studies include course content on middle powers or Australian or Canadian foreign policy. While the term ‘middle power’ has risen dramatically and is used in numerous academic papers, a deeper understanding of what the concept means is yet to spread widely.

South Korea is not yet using middle power diplomacy. It started the engine with crisis diplomacy but is no longer steering the vehicle. And without middle power diplomacy, the vehicle will ultimately end up in the same fiery crash that has befallen previous attempts to address issues relating to North Korea — or worse. Moon may be pursuing a new approach to North Korea, but it is not middle power diplomacy.

Jeffrey Robertson is a Visiting Fellow at the Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy at the Australian National University and Assistant Professor at Yonsei University in South Korea. He is author of Diplomatic Style and Foreign Policy: A Case Study of South Korea (Palgrave 2016).

I’m afraid that this article displays very poor understanding of South Korean foreign policy. To begin with, the relationship with North Korea isn’t a foreign policy issue from a South Korean perspective. Period. To claim it is shows limited knowlege of South Korean domestic politics and foreign policy. Furthermore, the characterisation of South Korean foreign policy-making is so simplistic that it borders on the ridiculous. North Korea policy comes from the Blue House because, again, it is a domestic issue from a South Korean perspective. However, most other key foreign policies come from ministries and change little across administrations: trade, US alliance, peacekeeping, China or energy are top foreign policy priorities in which the main goals and policies have been relatively unchanged for some 20-25 years despite some tinkering across administrations. It is fine if the author has an anti-South Korea bias, quite obvious throughout the article. But at least support this bias with a proper analysis of South Korean foreign policy.

Thanks Mark. I understand your point. However, I am not writing from a “South Korean perspective”. To me, foreign policy is the state’s pursuit of national interests in the international environment. Regardless of your political views, South and North Korea are separate states and interact as such in the international environment. In 800 words, many things can come across as simplistic. Try reading “Diplomatic Style and Foreign Policy: A Case Study of South Korea” (Routledge 2016) for a more detailed view. As for an “anti-South Korea bias” – no, not all. You confuse criticism for disfavor.

Mr. Robertson’s article could comprise a university course on South Korean foreign policy and the debate over middle power agency in East Asia. Bravo! His appreciation of Seoul’s deft reactions to the crises and opportunities of 2017 gives way to his (assumed) frustration with it’s follow-on behavior during 2018, as it failed repeatedly to use its’ latent leverage to put a hand on the scales of diplomatic developments. Seoul’s gamble that Washington would (suddenly) adapt a strategic view at the Hanoi Summit was tragically dashed, and a re-thinking of its role is in order. Without saying so explicitly, Robertson implies that a more structurally-grounded and transparent policy-making process could begin to make Korean policy more bold, relevant and defensible. Excellent and insightful.

Thanks Stephen. I think there’s some interesting research to be done on transparency in policy-making. I’m actually completing an article on this at the moment. There’s been great improvements – but still much further to go.

Always smart analysis from Prof. Robertson, but the fundamental problem with this and similar analyses which speak of SK incompetency and US incorrigibility (or vice versa) is that they ignore NK agency. Moon tried some MP diplomacy in Europe, SE Asia, with the IMF. And, he has done a masterful job ‘managing’ Trump’s ego so that the US has blocked Moon’s rapprochement with NK, which has gone a long way toward normalizing the NK state and apparently removing any threat of war from the SK perspective. He maneuvered Trump from a war footing and personal attacks on Kim to two summits – further normalizing NK – and a “love” relationship between the leaders. The ‘war games’ have largely stopped; Trump is refusing to add sanctions against NK; and sanction enforcement measures have significantly declined. And, of course, Trump is following Moon’s lead in ignoring NK human rights abuses. But, in the end, unless NK actually does something that demonstrates a commitment to denuclearization – say, handing over a couple of nukes – no amount of MP diplomacy can overcome the view among objective leaders and diplomats that this looks like just the latest round of NK gaming the system to get sanctions relief.

Thanks Joe. You’re dead right. I guess that I just accept North Korea agency as a given. But regardless of how NK games the process, I still would argue that the potential for securing SK aims would improve through a more strategic diplomatic approach.