These are no mere technical, economic policy developments. They change the whole posture of the United States in the global economic and strategic order. Nor are they developments uniquely associated with the administration of Donald Trump. Mr Pence’s side-speech at the Hudson Institute, indeed, was more a reflection of the deep undertow of developments in Washington’s security community and a reflection of thinking on lower Main Street, represented most prominently by Peter Navarro, Trump’s semi-discarded adviser, rather than Trump himself.

That future has arrived, says Robert Kaplan, who’s been mobilising the security troops for the ‘new Cold War’ for some years. ‘The constant, interminable Chinese computer hacks of American warships’ maintenance records, Pentagon personnel records, and so forth constitute war by other means’, he writes. ‘This situation will last decades and will only get worse, whatever this or that trade deal is struck between smiling Chinese and American presidents in a photo-op that sends financial markets momentarily skyward. The new cold war is permanent because of a host of factors that generals and strategists understand but that many, especially those in the business and financial community who populate Davos, still prefer to deny. And because the US–China relationship is the world’s most crucial—with many second- and third-order effects—a cold war between the two is becoming the negative organising principle of geopolitics that markets will just have to price in’.

Under this logic, it has even become difficult for presidential candidate Joe Biden to say ‘wait on there’ and to remind US audiences that their country can be in this contest from a position of competitive strength, not defensive weakness.

This powerful force in American thinking should come as no surprise. The United States has been a hegemon of unparalleled power and influence in world affairs for the best part of a century. Its relative power is in unquestionable decline. The underlying call to arms in a new Cold War is provoked by the growing fear that China will overtake the United States — economically, technologically and comprehensively. The psychosis, like many psychoses, has some grounding in hard fact.

In terms of sheer GDP, China’s overtaking the United States is almost inevitable, even if its growth suffers a sharp setback to 4 per cent from its current 6 per cent. At very best, the US economy will grow at 3 per cent over an extended period. It’s just a question of arithmetic whether China’s overtaking of the United States will happen in ten or 50 years’ time. China is already the world’s largest trader and the United States is in second place.

Economic power does not guarantee military power, but enables it. And China is filling that space — though nowhere in America’s league.

Supremacy in technology is another matter. The United States could remain in the technological lead for the indefinite future — unlikely to be as pre-eminent in the decades ahead but still up there with the front runners. Whether that turns out to be the case depends crucially on how a United States, relatively and inexorably diminished despite its reservoir of great industrial, technological and scientific power, continues to relate to a growing rest of the world, including but not only China.

A new Cold War would cut off trade, investment and technological links with not only China but also China’s large and many economic partners globally. It would certainly do immediate damage to China and weaken other economies, like Japan, ASEAN and Australia, around the world. But it would also do damage to the United States itself. It would accelerate the US shrinking, with immediately weakened growth and technological reach, and with problematic outcomes in the longer term. Cutting the United States off from technological engagement with China and other countries weakens China’s and others’ technological and scientific capacities, but also weakens America’s.

In its global strategy report, Anjani Trivedi says, MIT noted that ‘America’s relative economic weight in the world has been declining for decades, and as other countries grow more prosperous, a growing share of global R&D is originating outside the US’. Collaborations between Chinese and European researchers will undoubtedly increase; Washington’s inability to persuade its allies to reject Chinese technology has shown the limits of its influence.

In our lead essay this week, Dmitri Trenin of the Carnegie Endowment in Moscow reminds us that it’s no G2 world we live in today and that defining strategies as if it were or could be is likely a loser’s game.

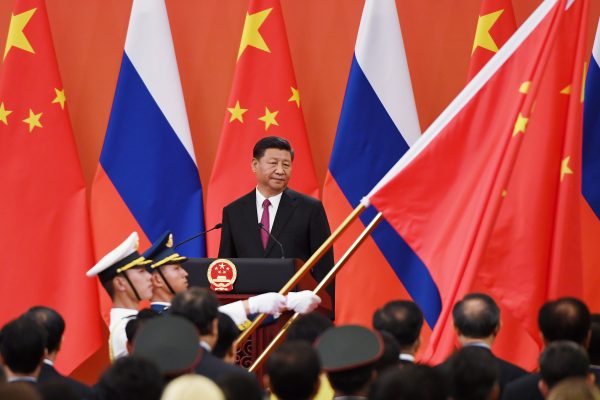

There is a new detente between China and Russia, says Trenin, a realignment that ‘is due to the inability to construct an inclusive world order that accommodates all major players after the Cold War. It also demonstrates the limits of single-power dominance — the Pax Americana — that could only last as long as the United States remained willing to carry the burden and other main actors acquiesced to its hegemony … Each country has its own agenda, objectives, strategies and tactics. This is a new pattern of relations, different both from the Cold War era and the European rivalries of the 18th and 19th centuries’. It’s not just China and Russia in this game. India, Africa and even Europe are in contest too.

In recent times the United States has dramatically undercut its own standing in mobilising allies and partners to its cause, reneging on its obligations under the rules-based economic system that it played such an important part in creating. A new Cold War is a dubious cause. China’s response to the challenge, of course, will be crucial to whatever the end-game may turn out to be.

For all the political doubling down domestically under Chinese President Xi Jinping, and the challenge of that to its continuing economic and other achievements, China has not retreated from the made-in-America global economic and political order on which its middle-income prosperity and security have been built. That is the premise on which engagement with China has been, and must continue to be based on, as the United States finds its way in the multipolar world that it helped to create.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.