Given a strong mandate, general economic advice suggests that an Indian government should undertake more liberalising reform in land and labour markets. But such attempts tend to stiffen political resistance and end in stalemates. Opportunistic reform by stealth — reform that intensifies and responds to trends at the margins — may be more feasible and is already transforming many intractable areas in India.

The government will need to act with renewed vigour to implement its manifesto — which aims to improve conditions of supply, lower costs throughout the economy and make living and doing business easier. Improving capabilities, strengths and risk-taking abilities is exactly the right approach for an aspirational India.

Specific focus areas include infrastructure, low-income housing, technology, health, education, water, the environment and facilitating the development transition so that migration from agricultural jobs will help increase farmer incomes. Diversification of rural incomes is already happening. Only 19 per cent of rural income now comes from cultivation and there is a major on-going shift to value addition in agriculture. Well-targeted direct benefit transfers will efficiently deliver relief to the most distressed at low cost and without creating market distortions. In light of drought conditions, the new cabinet’s first decision was to approve income transfers to all farmers.

Administrative reform was under-delivered by the previous government. Police and judicial reforms, as well as moves to simplify laws and to induct outside expertise in government, are now on the anvil. The ease of doing business index is being used as a trigger to improve coordination across government departments with the help of a special logistics cell.

The ranking of states is encouraging competitive market reform and public goods provision. Websites provide information on best practice, while inter-state discussion forums are being revived to aid convergence. Innovations in technology and communication aim to encourage entrepreneurship, remove discretion and corruption in public services and improve land records and markets — already making a critical difference.

The government did undertake standard structural reform in the macroeconomy — inflation targeting and fiscal responsibility legislation — and in finance with the adoption of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), along with further action against corruption. Inherited macroeconomic frailties made these necessary. As major loans from government banks had gone to private business, a bankruptcy regime had to be put in place to prevent the entire burden of resolution falling on taxpayers. But over-reaction made macroeconomic policy too tight and highlighted the dangers of orthodox reform, without modification to suit the context.

In the low global interest rate post global financial crisis environment, credit grew sharply in most emerging markets. India was an exception — credit growth was among the lowest and real interest rates among the highest globally. Private investment has been stagnant since 2011, unemployment is rising and growth for the first quarter of 2019 fell to a five year low of 5.8 per cent, below growth in China. Growth volatility suggests structural reforms alone are inadequate — more balanced countercyclical macroeconomic policies are needed.

As inflation is low, monetary policy has room for rate cuts. This should go together with greater provision of durable liquidity that will encourage banks to lend and specific liquidity to stressed sectors that do not have access to lender of last resort facilities and so are hoarding liquidity. This creates spill-overs to the rest of the economy. The returning government is likely to recommit to fiscal consolidation, maintaining the space for monetary stimulus.

Even so, there is some limited space for a fiscal stimulus. The pre-election slowdown in government spending can be reversed and planned expenditure for the year frontloaded. A list of reforms ready to go, including privatisation, will be fast-tracked. Goods and Services Tax (GST) simplification is one reform being looked at, but despite this and the possibility of tax cuts, revenues from GST are rising both because new information is being acted on more intensively and because the elections have concluded. There is scope for merging and pruning wasteful and maturing schemes, making funds available for re-allocation in line with current priorities.

The financial sector clean-up will continue. A more comprehensive recapitalisation of banks is possible now with bankruptcy and governance reforms in place. In the longer-term, regulations must be made uniform so that different financial entities grow to complement each other instead of regulations that encourage arbitrage. Improving the supply-side will attract more FDI seeking alternatives to China under current trade war conditions.

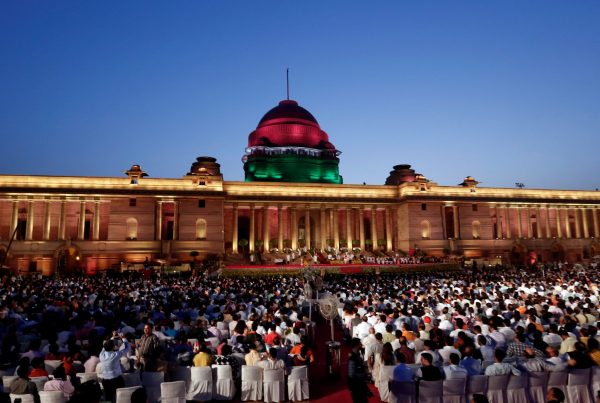

A massive vote has returned the Modi government. This stronger mandate will allow it to be a government for all, not just those who voted for it. It will reward progressive, inclusive and moderate stances since the fringe has less clout. Modi and his team will have their hands full, but this time around he will be able to build on what worked while suitably modifying what did not.

Dr Ashima Goyal is Professor of Economics at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR), Mumbai.

1-Reform in bureaucracy is also need of the hour.

2-While IBC is a much needed reform, it has not been able to deliver on account of undue delays caused by frequent litigation resulting in huge losses to the Banks. Hence there is need to plug the loop holes. This could be an important agenda in the Judicial reforms (by re-defining the jurisdictions of NCLT/NCLAT/HC/SC) alluded in the article.

3-It is mentioned in the article that the private investment has been stagnant since 2011. This needs to be re-checked.