The question of how North Korea is faring under sanctions is often asked without defining what is being measured. Some of these discussions seem more about making a judgment on US President Donald Trump than the North Korean economy.

Analysing the economic impacts of sanctions on North Korea will not prove if Trump’s ‘maximum pressure’ policy is good or bad. There are two issues that need consideration — how sanctions are impacting the economy and where the economy figures in the regime’s cost–benefit calculations regarding its nuclear and missile programs. The latter is ultimately what the sanctions are seeking to undermine or force North Korea to abolish entirely.

As with everything related to North Korea’s domestic workings, the first question is difficult to answer with full certainty. But a few indications do paint a somewhat solid picture of the state of the North Korean economy under sanctions. These suggest that while the economy is hurting badly from sanctions, it is not in a state of catastrophe. At least not yet.

In the longer run, things could become more dire if current difficulties persist for the country’s industry. For example, it is hard to see how any meaningful level of production of the most essential goods can continue. Still, catastrophe is a strong word. The resiliency of a regime that survived a devastating economic collapse and famine in the 1990s and early 2000s should not be underestimated.

Under the sanctions, North Korea is unable to sell its most crucial export goods. In 2018, Chinese imports from North Korea plummeted by 88 per cent. UN numbers show that Chinese imports of North Korean coal, iron ore and other natural resources increased dramatically from 2010 onwards. But China imported no coal from North Korea between January and March 2018. Chinese trade data might not be fully reliable, particularly on politically sensitive topics like imports of sanctioned goods from North Korea. It certainly doesn’t cover smuggling, for example. All the same, it’s unlikely that Beijing would have imported any significantly large quantities of coal from North Korea and simply left them entirely off the books.

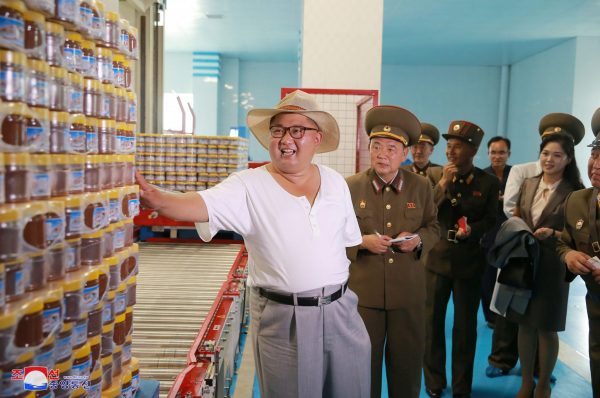

These exports have likely been a crucial source of funding for North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s prestige projects in infrastructure and other spheres. With such exports plunging, the North Korean economy is clearly taking a major hit — some coal mines and factories ceased operations following sanctions.

In the short run, the lower coal prices may ironically be contributing to a boost in some industrial production as electricity costs have sunk dramatically due to lower foreign demand. In the longer run, it means one of the regime’s main sources of foreign currency earnings are gone.

Some say that smuggling renders the sanctions regime ‘invalid’. But this is a contradiction — had sanctions not had an impact, smuggling would not have been necessary in the first place. Smuggling is expensive. Whatever goods North Korea imports through smuggling have an added risk premium, and it likely gets paid much less than it normally would for whatever it exports through illicit channels. The quantities it can import and export under the radar cannot be anywhere near pre-sanction levels.

Even with these difficulties, no disaster seems to be looming in the immediate future. While market prices and exchange rates have held remarkably stable throughout the ‘maximum pressure’ period, they do not tell the full story on the country’s economic situation. There are ways to explain price stability in the face of mounting difficulties. Even so, market prices should show signs of stress if the country was truly plunged into an abrupt disaster. North Korea is clearly muddling through for now.

But as long as sanctions remain in place, it will not be possible for Kim to meaningfully improve North Korea’s poor, underdeveloped economy. North Korea can survive under sanctions, but it cannot do much more.

How sanctions figure in the regime’s strategic calculations is a much more difficult question. It is unlikely that the sanctions will result in social instability that truly threatens the regime’s hold on power. The regime is no stranger to brute force, a resource that it has in abundance.

Should things get truly catastrophic, China — and perhaps Russia — would likely intervene in order to keep the risk of social instability at bay with donations of food, fuel, and maybe even foreign currency. It is likely that China is already shoring up North Korea to some degree by providing key resources that may be difficult to acquire due to sanctions. The government clearly prioritises nuclear weapons over economic development.

We still do not know if the sanctions are ‘working’. To understand their full effect and potential on their primary target groups, the sanctions would need to be in place for several more years.

It remains to be seen if there is sufficient political patience in the United States to keep the sanctions pressure up for long enough, and whether China is prepared to continue implementing the sanctions. History suggests that both are unlikely, but perhaps this time is different.

Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein is an Associate Scholar at the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI), Editor of North Korean Economy Watch and a Doctoral Candidate of the Department of History, the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.