The show of force in the Northeast Asian skies was meant to signal the growing strength of the China–Russia strategic bond and the main target of this message was Seoul.

The patrol’s route ran over the Dokdo (Takeshima) islands, one of the most politically sensitive areas in East Asia. The islands are disputed between South Korea and Japan, so the China–Russia operation caused a commotion. Seoul and Tokyo both claimed that a Russian military plane from the joint patrol group twice violated Dokdo’s airspace, prompting South Korean interceptor jets to fire hundreds of warning shots. The Russian and Chinese governments categorically state that the mission took place over international waters and did not breach any sovereign airspace.

Whether or not an actual violation of the airspace over Dokdo took place, this first joint mission by Russian and Chinese air forces carries major diplomatic and strategic significance. By executing an operation in the Northeast Asian skies, Moscow and Beijing are sending the message that their ‘strategic partnership’ is not a paper tiger — it is becoming a political–military force to be reckoned with.

In 2016, Chinese and Russian warships simultaneously sailed close to the Japan-administered but China-claimed Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands, raising suspicions that the manoeuvres were coordinated. Then, Moscow and Beijing refrained from any comments, neither confirming nor denying Japanese suspicions. But this time China and Russia apparently sought a maximum demonstration effect.

Apart from displaying the strengthening political–military ties between Moscow and Beijing, the joint operation had the practical purpose of enhancing interoperability of Russian and Chinese air forces. According to Russian sources, the objective was also to collect valuable military data about the South Korean air defence system by deliberately provoking its response, something called ‘cracking the hedgehog’ in Russian military jargon.

Russia and China are now negotiating a new military cooperation agreement. It will replace the previous agreement concluded in 1993 and will likely reflect a new level of their political–military partnership. There is little doubt that the joint patrol on 23 July is just a harbinger of what may come next. The China–Russia military missions outside their borders are bound to continue, with increasing scale and sophistication.

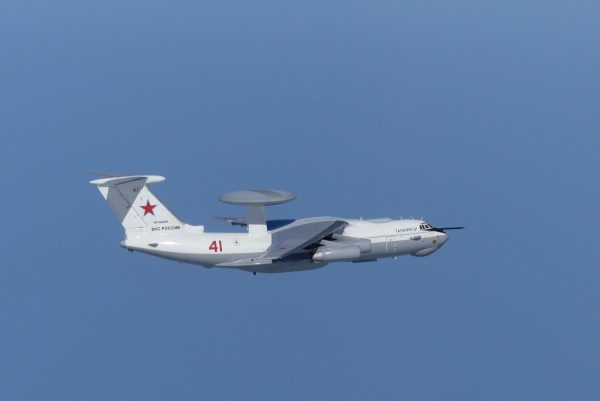

Some Russian analysts believe one of the next steps in the military collaboration could be forming a shared pool of support assets, such as AWACS aircraft and tanker aircraft, to assist Russian and Chinese forces operating in the Pacific. Russia and China are also likely to enhance already established patterns of their military cooperation, including weapons sales and large-scale military drills like the Vostok 2018 exercise held in Russia’s Far East.

If the China–Russia military partnership continues its upward trend, it will inevitably affect the security order in the Western Pacific. The joint actions by Russia and China are most likely seeking to challenge the system of US-centred alliances in the Asia Pacific and change the strategic balance. By acting individually, neither could hope to undercut US hegemony in the Pacific.

Are China–Russia patrols and other combined military missions beyond East Asia possible in the near future — for example, in the Atlantic, Middle East, Arctic or even the Caribbean? This cannot be ruled out, especially as China grows its power projection capabilities and builds a network of overseas military bases (such as in Djibouti and Gwadar).

On the other hand, Northeast Asia is currently the most suitable theatre to operationalise a China–Russia military alliance. Russia and China have a direct presence in the region, where they maintain substantial military potentials that — if combined — can complement each other. And importantly, it is in the North Pacific that they interact with the United States. If the China–Russia military alliance is to materialise, it will most likely start from Northeast Asia.

The joint patrol of Russian and Chinese warplanes was a message to Washington, Tokyo and Seoul. But it was Seoul that appears to be the main target. The bombers could have flown by the Senkakus or Okinawa, but they chose the Korean-controlled Dokdo. It was the first violation of South Korean airspace by a foreign military plane since the end of the Korean War.

Beijing and Moscow see South Korea as a relatively weak link in the US alliance network in Asia, compared to the two other main US allies, Japan and Australia. South Korea is more vulnerable than Japan to pressure from the China–Russia coalition. If Beijing and Moscow adroitly use the carrot and stick approach toward Seoul, it could perhaps even weaken the US–South Korea alliance.

Displays of military might is just one of the ways to influence Seoul. South Korea’s economy is highly dependent on China. Moreover, Beijing and Moscow’s ties with North Korea give them power to affect the situation on the Korean Peninsula. Russia and China might be looking to turn South Korea into a neutral state that would refrain from policies the two countries view as compromising their security. If this ‘Finlandisation’ was achieved, it would be a major blow to the United States, both in Northeast Asia and globally.

Artyom Lukin is Associate Professor and Deputy Director of Research at the School of Regional and International Studies, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok.