The government’s outlook on promoting a cashless society includes the issuance in 2018 of a policy document titled ‘Cashless Vision’ and the start of a massive subsidisation program to promote cashless payments in October 2019. This subsidy aims to promote the transition to cashless payments while also mitigating a drop in consumption caused by the consumption tax hike from 8 per cent to 10 per cent that came into effect the same month.

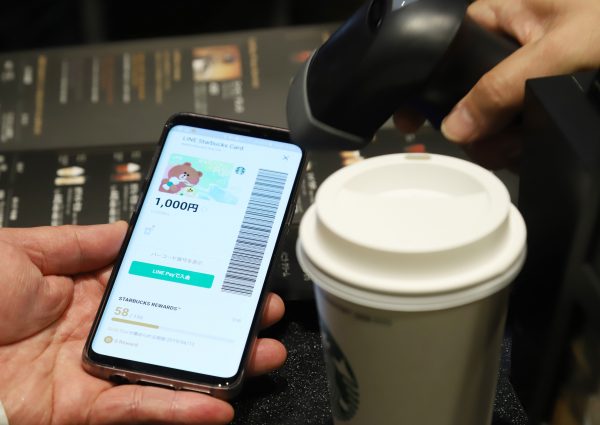

Parallel to government initiatives, Japanese consumers are witnessing fierce competition among cashless payment providers. This particular market has seen the entrance of a significant number of smartphone-based payment providers such as PayPay, LINE Pay and Merpay. This is in addition to traditional cashless methods such as Suica or Pasmo card for public transportation, and various brands of credit cards.

This raises the question of why the Japanese government and providers are so eager to promote cashless payment, and how likely it is that their attempts will succeed?

Since its rapid growth in the 1970s, Japan has enjoyed a strong reputation as a country at the forefront of high-tech innovation. This reputation is a result of a successful manufacturing industry, especially in automobiles and electronics.

In contrast, the services sector has been regarded as a less competitive division of the Japanese economy. For example, the Japanese economy failed to foster technology start-ups in the global software and IT services industry. In another example, despite the cutting-edge innovations that led to the first internet-connected cellphone architecture ‘i-mode’ in 1999, the system has never become a global standard. In contrast to Japan’s high level of scientific research, social adaptations and global business strategies have been long-standing challenges to Japanese innovation.

In addition, another factor that has encouraged leaders to take a bold step towards a cashless society is Chinese competition in technological innovation. Since 2010, the Chinese tech industry has exhibited massive advancements in the adoption of cutting-edge technology in various services from cashless payments to ride sharing and Online to Offline (O2O) retail.

One particular service that attracted Japanese attention was the use of the QR code (originally invented by a Japanese company), provided through Alipay or WeChat Pay. This innovation coincided with a rapid increase of inbound tourists from China into Japan — now, the logos of Alipay and WeChat Pay can be observed in many Japanese retail stores. The exposure to Chinese cashless payment options has caused a sense of crisis in Japan and a fear that the Japanese economy is falling behind.

Driven by this sense of crisis and expected business opportunities, cashless payment has become key to reviving Japan’s reputation as a leader in cutting-edge technology. The Japanese government has decided to invest 280 billion yen (US$2.5 billion) to subsidise retailers and consumers who use cashless payments.

Although there is an expectation that cashless payments present unique business opportunities, there are several key barriers Japan must overcome before it becomes a cashless society, and these factors also explain why Japan has been so heavily cash dependent.

The first challenge is the high cost of adoption for retailers. One of the reasons for the success of QR code based payments in China is the low cost of investment and transaction fees. It requires only conventional smartphones or paper QR-codes for retailers. In contrast, contactless-card payments in Japan require a significant investment in equipment and payment of transaction fees. It is unclear whether government subsidisation will sufficiently lower costs to ensure the transition to cashless payments is a sustainable option.

Another barrier to the penetration of cashless payments is perceived inconvenience. Cashiers in retail stores are well trained and can complete a payment with cash in just a few seconds. On the other hand, smartphone-based systems require several steps to finalise payments. The benefits of cashless payments need to be desired and will involve integration with other internet services.

The consumer perception of risks associated with cashless payments is another key challenge. Research has shown that a significant portion of Japanese consumers prefer cash because they fear overspending with cashless methods. Security is also a practical barrier and concern for consumers given that security breaches and improper use of personal data are frequently reported.

Soichiro Takagi is Associate Professor at the Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies at The University of Tokyo.