This could have long-lasting implications for Australia’s ‘Pacific step up’ and New Zealand’s ‘Pacific Reset’, as well as for the credibility of other regional actors such as the United States.

But the temptation to frame current events in solely geopolitical terms obscures key strengths and weaknesses within the Pacific itself. This a test of regional leadership. How effectively and decisively the Pacific’s partners respond to the region’s health security needs will be the measure — and the legacy — of these relationships and policies.

Despite concerns that the pandemic would present an opportunity for China to deepen its influence in the region, it may find itself left out in the cold. Certainly, Beijing initially sought to control and shape the pandemic narrative in the Pacific. For example, officials have privately cited efforts by Chinese diplomats to persuade their government not to evacuate their students or to moderate government restrictions that would signal a lack of confidence in China’s leadership. Despite this, 50 Pacific Island students were evacuated from Wuhan on flight NZ1942.

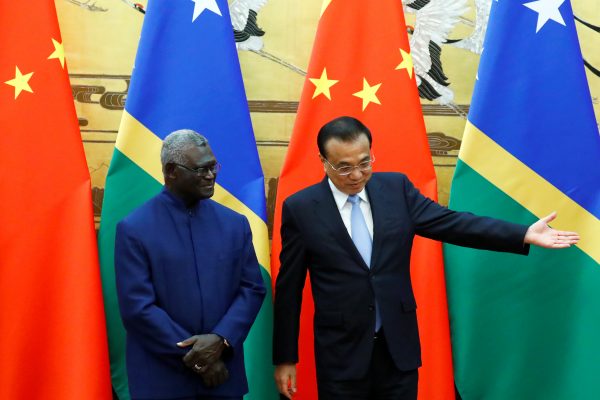

Beijing has also attempted to leverage a form of emotional blackmail, pitching the crisis as a friendship test and using its economic weight to discourage countries from closing their borders. In Solomon Islands, the Head of the Chinese Embassy Taskforce, Yao Ming, asked the government — which switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing in 2019 — to ease its travel restrictions so that Chinese diplomats could travel there. Yao claimed it was in the Solomon Islands’ best interests to ease the ban to protect the local economy.

At the same time, Beijing is stepping up its technical and advisory assistance to Pacific states. On 10 March, senior officials from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the National Health Commission, as well as Chinese ambassadors to Pacific island states, held a video conference on COVID-19 with Pacific partners. Hosted by the Chinese Embassy in Port Vila, Vanuatu, the conference brought together over 100 officials and health experts from across the region, including Papua New Guinea’s Minister of Health, the Acting Minister of Health of the Federated States of Micronesia and the CEO of Tonga’s Ministry of Health.

China subsequently established the US$1.9 million China–Pacific Island Countries Anti-COVID-19 Cooperation Fund and sent medical equipment to French Polynesia after aid from France was not forthcoming. It has also provided assistance to enable Solomon Islands to undertake testing in-country. And it has donated US$100,000 to Vanuatu and US$200,000 to Tonga towards COVID-19 preparedness.

These are token amounts when compared with the US$123 million in COVID-19 aid Australia has allocated to Papua New Guinea. Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s reference to a reconfiguration of development assistance suggests this is a redistribution of funds allocated to existing programs, rather than an actual increase. But this may be due to a need to expedite the availability of funds.

The battle of the narratives is less about ideology than capacity, but it has won favour in certain Pacific quarters. In his parliamentary address, Samoan Prime Minister Tuilaepa Aiono Sailele Malielegaoi stated that he favoured China’s no-nonsense approach in the fight to control the spread of the coronavirus. He suggested that the ‘principles of human rights in democratic countries’ impeded response times, whereas China’s ‘pragmatic communism system of governing’ produced quick successes in the control of the disease.

Claims made by Australia’s opposition that China and New Zealand were filling the leadership void led to our call for a collective regional response to COVID-19. Morrison recently stated that ‘there has never been a more important time for Australia’s Pacific step up’.

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) has announced that a coordinated regional response is under discussion in consultation and partnership with the World Health Organization and the Pacific Community. The response will be mandated under the 2000 Biketawa Declaration, which provides a clear framework for coordinating responses to regional crises and previously mandated interventions in Solomon Islands, Tonga and Nauru. PIF Secretary-General Dame Meg Taylor stated: ‘If ever there was a time where the region and its partners needed to work together in strong solidarity to overcome a direct and immediate threat to the lives of our people across our Blue Pacific region — it is now’.

Several Pacific states have already developed national responses, which may complicate regional coordination. Moreover, Dame Meg’s call is for cooperation across all partners. Therein lies the catch for China. To be truly effective, Beijing’s efforts will need to support the regional response rather than circumvent and potentially undermine it. Australia and New Zealand will also need to heed the message.

COVID-19 will test the Pacific policies of the region’s partners. China has reinvented itself as a benefactor. Its assistance will be welcomed by Pacific states at a time when there appears to be a leadership vacuum at the regional level. But a protracted pandemic scenario will prove a challenge for Australia and New Zealand. They have long feared a situation where disasters simultaneously occur on the home front and in the Pacific, demanding a balancing of domestic needs with those of Pacific neighbours.

Despite the United States’ Pacific Pledge, Washington’s interest in the Pacific beyond the compact territories, freely associated states and Hawaii may waver in the face of significant domestic upheaval. That said, US Indo Pacific Command will likely a US response. France and the United Kingdom will similarly struggle to sustain engagement, to the detriment of their regional credibility.

The Biketawa Declaration calls for responses to crises to be credible, coherent and consistent, to stay the course, and to be underpinned by cooperation and consensus. If these principles are upheld, Pacific states themselves will be the vanguards — and not just beneficiaries — of a collective response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Anna Powles is a Senior Lecturer of Security Studies at the Centre for Defence and Security Studies, Massey University, Wellington.

Jose Sousa-Santos is a Visiting Fellow at the ANU Cyber Institute, Senior Associate (Pacific Regional Security) at Victoria University’s Centre for Lifelong Learning and a Research Scholar at the Joint Centre for Disaster Research, Massey University.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on the novel coronavirus crisis and its impact.