Leaders argue over the pandemic’s origins, when it is well understood that similar pandemics occur repeatedly. Even with partially-closed borders, it takes few carriers to spread such viruses. Given the large and highly-interconnected global population, increasing collective capacity to identify, monitor and tackle such global threats is crucial.

The pandemic has metastasised from a global health crisis to a global financial, economic and geopolitical crisis. Drastic ‘outside the box’ thinking and measures must be rolled out to avoid the worst consequences. No country can escape the crisis. Only the G20 today can coordinate such an undertaking.

Despite countries claiming to be ‘waging a war’ against the virus, nothing of the same effort has occurred. There are several possible reasons but without question the rising nationalist tide has turned many towards protective and protectionist measures. There seems no more dramatic turn to nationalist policymaking than in the United States and China.

The pandemic underscores how US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, and their officials, have undermined collaboration between the two largest powers. Brookings President John Allen wrote during the early stages of the pandemic, ‘here is the opportunity for these two great nations to find common cause and purpose … Trump and Xi must demonstrate global leadership and join together to pool their significant scientific resources, literally, for the good of all humankind’.

Trump and his ‘America First’ policy was quick to close borders and suspend flights. He was far less eager to call for multilateral efforts, and insisted at first on calling the outbreak the ‘Chinese virus’. Meanwhile China was prepared to offer assistance. China’s Foreign Ministry announced that it was sending medical equipment to hard-hit countries like South Korea, Iran and Iraq. China also sent teams of medical professionals to assist Italy. These efforts emerged after the outbreak was under control in China. But the efforts were bilateral and there was no clarion call for a collective effort.

It is vital that all significant actors take steps to collective action. Effective multilateralism is more urgent today than ever. Yuval Noah Hariri urged: ‘If the void left by the United States isn’t filled by other countries, not only will it be much harder to stop the current epidemic, but its legacy will continue to poison international relations for years to come … We must hope that the current epidemic will help humankind realise the acute danger posed by global disunity’.

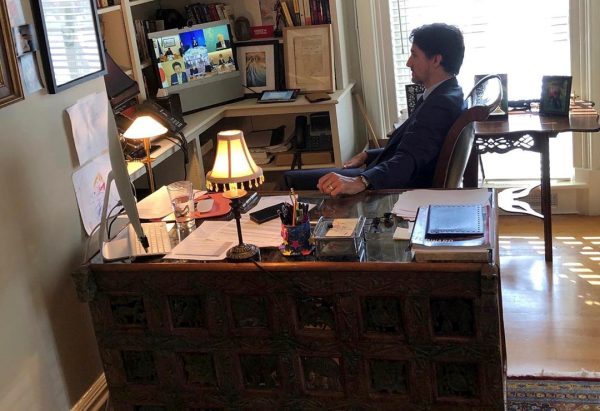

Experts from Europe, Canada, Chile and the United States held a virtual workshop on China–West relations on 20 March hosted by Boston University’s China Initiative and organised by the Vision20 co-chairs. This workshop drew together China scholars, international relations experts and economists to examine US–China relations and articulate pathways for a better balance between coexistence and competition.

The China–West Dialogue group reached a consensus quickly, calling on global leaders to cease the ‘blame game’ and begin rethinking the emerging global order. This critical view of collective effort was underscored by former British prime minister Gordon Brown, a vital participant in the G20 effort to respond to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Brown declared: ‘Our plan to reframe global institutions for an age of global capital flows and supply chains also failed. But at least all realised that if we did not stand together, we would fall separately. It was the unanimous commitment to shared objectives, built on the rock of practical measures, that helped restore confidence where there had been none’.

In March 2020 the G7 held both a virtual summit of finance ministers and a meeting of foreign ministers. The G7 foreign ministers’ meeting failed to issue even a final communique, owing to the refusal of the other six countries, plus the European Union, to go along with US insistence on calling the virus the ‘Wuhan virus’. The G7 finance meeting produced a statement affirming that G7 countries are ‘taking action and enhancing coordination on [their] dynamic domestic and international policy efforts to respond to the global health, economic and financial impacts associated with [COVID-19]’.

G20 leaders met virtually on 26 March. Despite the urgency, the leaders’ recommendations remained aspirational and lacked concreteness to have operational meaning. The Leaders’ Statement underlined a need to act collaboratively to: protect lives, safeguard people’s jobs and incomes, restore confidence, preserve financial stability, revive growth and recover stronger, minimise disruptions to trade and global supply chains, provide help to all countries in need of assistance and coordinate on public health and financial measures.

Following the Leaders’ G20 virtual summit, and as a result of it, G20 trade ministers gathered virtually and declared any ‘emergency measures’ to address the coronavirus pandemic must be temporary and consistent with WTO rules. Additionally, the trade ministers tasked the G20 trade and investment working group to address related issues and identify ‘additional proposed actions that could help alleviate the wide-range impact of COVID-19, as well as longer-term actions that should be taken to support the multilateral trading system and expedite economic recovery’.

Aspiration and rhetoric. But now G20 ministers need to put concrete national and global policies in place.

Alan S Alexandroff is Director of the Global Summitry Project at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, The University of Toronto, and Co-Chair of the Vision20.

Colin Bradford is a Non-resident Senior Fellow of the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution and Co-Chair of the Vision20.

Yves Tiberghien is Professor of Political Science, The University of British Columbia, and Co-Chair of the Vision20.

This article is part of an EAF special feature series on the novel coronavirus crisis and its impact.