This boils over into problems between states. The most recent manifestation of this has come via public comments by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying about a US-supported laboratory in Kazakhstan that was darkly alluded to within the context of the global health crisis, hinting it might have been part of the problem. This comes after earlier spats over nationalist online content from China and disagreements between Chinese and Kazakh doctors about how they were handling the crisis. As with many things around the world, COVID-19 has exacerbated existing issues, highlighting the tensions that bubble beneath the surface in Central Asia.

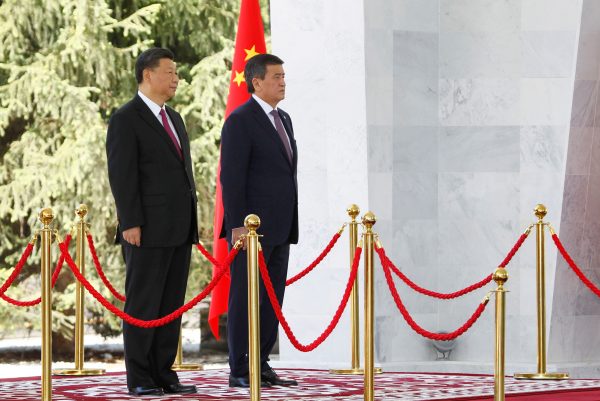

These disagreements in Kazakhstan come among other problems between the two in the region. In mid-February this year, protests against the construction of a free trade zone in At-Bashi, Kyrgyzstan led to the cancellation of the US$280 million project which was initially signed during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit last year. It is not clear whether the Chinese firm withdrew or the Kyrgyz government annulled the contract, but the protests crystallised the decision to stop the project.

These public protests are driven by a long-standing fear that China will overwhelm the region. In this particular case, this fear might also be undermining Kyrgyzstan’s own interests, as the At-Bashi project would have been beneficial for Kyrgyzstan’s regional trade ambitions. But, the fear is in part built off the back of a series of bad experiences with individual projects or deals which have polluted or caused other problems, failed to employ people as the public expected or were largely subsumed by corrupt local figures. There is also an undercurrent of racism and Sinophobia to this anger, which has grown among some as people learn of the mistreatment of minorities in Xinjiang and more recently around the spread of COVID-19.

But the other unspoken element is a sense of humiliation that many in the region feel, a fear that they may lose their sense of national identity to China. Central Asia is made up of five young countries that only recently started to develop the identity of a nation-state. This desire to create a national identity encompasses a perceived need for one’s own language, airline, currency, national food and history.

From this perspective, giant China is a huge concern. Already still closely linked to Russia, Central Asians have little desire to let their national identity be subsumed by China. They did not leave the Soviet Union to simply fall into the thrall of another Communist power.

All of this helps explain a recent diplomatic clash between Kazakhstan and China. An article published by a private Chinese online media company recently seemed to suggest that Kazakhs were keen to be reabsorbed into China. The result in Kazakhstan was swift and negative — the Chinese Embassy received a call from the Kazakh Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanding an explanation and the removal of the article.

The Kazakh reaction is in some ways excessive. While it is true that all media in China is to some degree state vetted, this does not necessarily mean that it is all created by the state. The article appears to be part of a series that emanated from a clickbait farm in Xi’an. It claimed that a number of countries wanted to ‘return to China’ including not only Kazakhstan, but also neighbouring Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, among others. The Chinese media has claimed the article is ‘fake news’ generated by profit-seeking content providers.

It is hard to imagine that Beijing has much interest in stoking anger among the neighbours with whom it has a largely stable relationship. Certainly the Chinese Ambassador’s attempts to place the blame on Western media suggests the Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not think the piece was a good idea. But the fact that content providers thought the article would generate positive interest within China suggests that there is a strongly nationalist domestic constituency that view China’s neighbours as lost provinces of their great country.

This sentiment arouses great concern in Central Asia, where there is palpable (if conspiratorial) fear that China’s infrastructure push is the first step towards some sort of an invasion.

But this does highlight a problem for Beijing: an elevated nationalism at home leads to problems abroad. This problem is exacerbated by the narratives that Beijing is advancing at home in response to COVID-19 — that China was not the source of the virus (and that it might be US-built laboratories in former Soviet countries like Kazakhstan), that China has defeated the virus, that China is giving medical equipment to the world, that China is only now suffering because of people from foreign countries. Given that in contrast the international media is full of accusations that Chinese labs leaked the virus, stories of faulty Chinese medical equipment and general anger at China’s handling of the virus, the clash between the two is clear. The result of this divergence for a domestic Chinese audience is angry nationalism.

This builds on nationalist sentiment that President Xi has been stoking since he came to power. For a Chinese audience that only hears domestic narratives, it has been a story of growth and prosperity — a China dream — that is now being stymied and attacked by outsiders. When nationalists talk of China’s neighbours wanting to be part of China, they are articulating the natural extension of this sentiment.

The Chinese government is ultimately most interested in what the Chinese people think. Stoking the fires of nationalism is an easy way to win them over — especially when painted against a historical narrative of overcoming a century of humiliation at the hands of foreigners.

Yet this nationalism will not always be directed in ways that Xi wants, particularly if it causes frictions with neighbours who are nominally friendly with China. Chinese nationalism may be a problem for the world, but if it goes too far it becomes a problem for Beijing too.

Raffaello Pantucci is Senior Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI), London.