The United States is missing from these agreements, having left the predecessor of the CPTPP (the Trans-Pacific Partnership) when US President Donald Trump took office. India, originally a member of the RCEP negotiations, withdrew just before the agreement’s conclusion. These departures hand China potent leverage — it is the largest economy in a now regionally focussed East Asian system.

Will China use this leverage to advance short-term political interests — a kind of ‘China first’ strategy — or to build a rules-based system that works for all countries as a model for global cooperation? How Chinese leaders answer this question will shape the economic and political landscape for years to come.

Simulations reveal the US–China trade war will reduce world incomes by US$301 billion annually, and world trade by nearly US$1 trillion annually, by 2030 from what they would be with pre-Trump policies. Nearly three-quarters of the decline in trade will consist of transactions across the Pacific.

In contrast, the CPTPP and RCEP could add US$121 billion and US$209 billion to global incomes, respectively, if they are implemented as planned. These gains — due to additional trade and production in East Asia — would offset the effects of the trade war for the region, if not fully for China and the United States. The agreements will reduce the cost of doing business and strengthen technology, manufacturing, agriculture and natural resources cooperation in East Asia. They will also deepen linkages among China, Japan and South Korea, which are among each other’s largest trade partners.

The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative will also reinforce these relationships. It will offer US$1.4 trillion in investments for transport, energy and communications infrastructure to neighbouring economies. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s offer of US$113 million in US investments highlights the gulf between Chinese and US priorities. The United States used to counter aid with good access to its markets but is now retreating into mercantilism.

RCEP and the CPTPP make East Asia a natural sphere of Chinese economic influence and will generate skewed benefits. China will gain the most from RCEP (US$100 billion), followed by Japan (US$46 billion) and South Korea (US$23 billion). Southeast Asia will also benefit (US$19 billion), but less since ASEAN already has free trade accords in place with its RCEP partners. The United States and India will forego gains of US$131 billion and US$60 billion, respectively.

The big question is how China will manage its new economic role. Some in China see compromise with other countries as unnecessary beyond the need for essential trade. That may explain policies to coerce even well-disposed trade partners to support China politically — for example, by warning Chinese students away from Australia, presumably in retaliation for Australian support for an inquiry into the COVID-19 pandemic.

But other Chinese leaders understand that the country faces acute international pushback. Regional concerns are well known and include a range of Chinese policies, from Hong Kong to the South China Sea, backed by a new ‘wolf warrior’ approach to diplomacy that alienates rather than persuades.

The Trump administration also pursues many unacceptable objectives and uses deeply alienating speech. But these do not change the fact that China cannot grow its regional or global influence by acting as an ‘unencumbered power’. Nor can East Asia become a regional model while many see China as a rising threat.

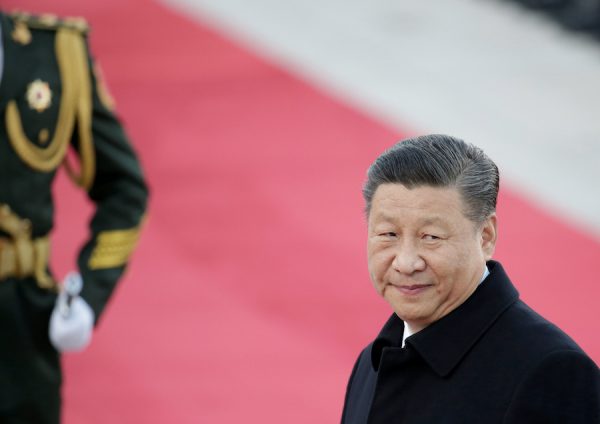

China’s interest in collaboration gained momentum in recent years, as suggested by accelerating dialogue with neighbouring leaders. China–Japan–South Korea trilateral meetings resumed in 2018. This set the stage for a state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Japan in April 2020, which was postponed due to COVID-19 and is now at risk of being cancelled in protest against the new Hong Kong national security law. Working with China is becoming a political liability for many regional leaders.

In these dysfunctional times, a new and inclusive regional cooperation model led by China would yield economic gains and meaningful political support. Mutually valued international partnerships have never been more urgent for China or the world.

RCEP and the CPTPP invite a positive Chinese approach. China stood by RCEP through years of rollercoaster negotiations under ‘ASEAN centrality’. It could now ensure that the agreement enters smoothly into force and is followed by collaborations with ASEAN on political issues like completing the longstanding Code of Conduct negotiations about the South China Sea.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s recent announcement that China is open to the CPTPP creates an additional opportunity. By signalling willingness to adopt global norms, China’s membership in the CPTPP would cheer markets and countries as a harbinger of future deals and global growth. Chinese membership in the CPTPP would add US$485 billion to world real incomes. The gains would exceed US$1 trillion if Indonesia, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan and Thailand also joined, offsetting the costs of the US–China trade war three-fold.

Joining the CPTPP would require China to adopt advanced international rules. Li no doubt understood, for example, that China would have to change its approach to supporting strategic sectors and enterprises to join the CPTPP.

But compromises are possible. Due to COVID-19, many countries now support a larger economic role for the state. Even the United States is using or proposing ‘buy American’ laws, controls on trade and investment, public investments in technology, and government stakes in global champions.

RCEP and the CPTPP will benefit China economically, but they put Chinese leadership to a test. They offer an unusual chance to reverse the freefall in international cooperation.

Peter A Petri is the Carl J Shapiro Professor of International Finance at the Brandeis International Business School, Brandeis University. He is also a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and visiting fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Michael G Plummer is the Director of SAIS Europe, Eni Professor of International Economics at Johns Hopkins University and a non-resident senior fellow at the East-West Center.

A version of this piece originally appeared here at the Brookings Institution.