In the 1990s, the desired state of the Japan–China relationship was described in terms of ‘peace’ and ‘friendship.’ There was no expectation that China would become a liberal democracy, but there was recognition that stable relations between the two countries were necessary for mutual and regional prosperity. When Japan sensed that China’s rise might have major geopolitical implications, potentially transforming the regional order in favour of China’s geopolitical ambitions, Japan again tried to tame the dragon by reaching a ‘mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests’. Japan reached this conclusion early on because of the ‘perils of proximity’.

This was precisely the moment when the world became fixated on China’s emergence on to the global stage. Not that everyone was optimistic about China’s rise — the concept of hedging was always there. But rather than isolating China, the goal of a hedging strategy was to facilitate engagement.

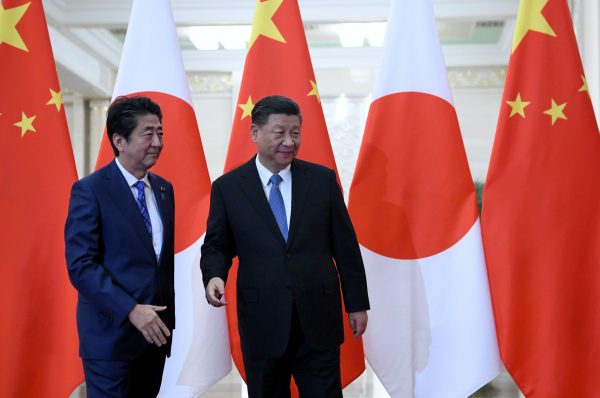

Though the term ‘G2’ was never an official US policy position, the Obama administration was initially ambitious in its approach towards China, seeing Beijing as a potentially trustworthy global partner. Other Western democracies saw China’s rise merely in terms of expanding trade relations. Countries in the region had mixed views but were relatively silent in expressing doubts about China’s intentions. Japan was often at the forefront of those nations expressing concerns about China’s hegemonic ambitions, particularly given China’s actions in the East China Sea.

Though Japan has many friends and partners in the region, Tokyo has often stood alone in expressing concerns about China’s actions. At one track-two multilateral regional conference I attended, a proposal from the Chinese delegation was met with deep concern from delegates in the corridors outside the conference room. When it came to the formal discussions, however, most countries remained silent, leaving only Japan and the United States to express opposition.

Despite this tendency, Japan has remained clear in rejecting China’s hegemonic ambitions in the region. Japan has never felt it can do so alone, leaving it with no option but to become a staunch alliance partner of the United States. Japan’s increasing assertiveness in national security affairs was often perceived as rising nationalism, but this assertiveness was almost always pursued in the context of strengthening the alliance and confirming US commitment by showing Japan’s resolve to do the maximum within the current legal framework.

In the post-Cold War period, Japan’s foreign policy was consistent — except for a brief moment during the Hatoyama administration — in pursuing the dual goal of deepening the US–Japan security alliance while maintaining good relations with China. This position may no longer be sustainable in light of the hardening US posture towards China and China’s intention to resist it.

The series of speeches delivered recently by the US National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, Attorney General William Barr, FBI Director Christopher Wray and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went far beyond what Japan expected of the United States in terms of confronting China. Secretary Pompeo’s needlessly antagonistic message was that of an ideological crusade against the Chinese Communist Party. Then again, China’s recent actions in Hong Kong and the South China Sea, mass internment of Uighurs in Xinjiang, its military build-up and malicious cyber attacks do put China in a different category from a developing nation feeling insecure about itself.

In this competition, Japan has already taken sides and is not hesitant to say so publicly. But this does not mean Japan is totally comfortable with the position taken by the current or every US administration. A more hawkish US policy may mean Japan no longer has to worry about US security commitments, and difficulties with the United States may lead China to seek a calmer relationship with Japan. But this delicate balance may easily spin out of control since there is no one in the driver’s seat managing the confrontation.

The recent visit to Washington by Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne and Defence Minister Linda Reynolds for the annual 2+2 talks may be relevant to Japan in thinking about the path forward. The two ministers stood firm with the United States on China, while still expressing Australia’s own position.

It is no exaggeration to say that the result of the US presidential election in November is a major geopolitical uncertainty. Though ‘toughness’ towards China may now be a constant in US policy, how that ‘toughness’ is converted into policy may vary a great deal. The China challenge is a certainty, but US policy after January of 2021 is not. Despite Pompeo’s call for allies to join the crusade, it is wise for Japan to maintain a smart distance, devising its own ‘tough’ policy towards China.

Toshihiro Nakayama is Professor of Policy Management at Keio University and Senior Adjunct Fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs.

This article appears in the most recent edition of East Asia Forum Quarterly, ‘Japan’s Choices’, Vol. 12 No. 3.