The question becomes more relevant given Japan’s domestic situation. Japan’s fiscal condition, including its massive deficit, is worsening under massive government spending to counter the pandemic impact. Japan’s GDP shrank a record 27.8 per cent between April and June. Inevitably, the new administration’s focus is on domestic economic recovery. There are nevertheless at least four reasons why the administration will likely carry on Abe’s foreign policy activism, represented by FOIP.

First, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga clearly emphasised during his election campaign for Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leadership that he would follow in Abe’s footsteps on foreign policy, including FOIP. As Abe’s chief cabinet secretary, Suga worked in the inner circle of the Abe government.

Suga’s career has equipped him with experience in dealing with mainly domestic affairs. He had previously served as a Yokohama City Council member. Suga has not yet raised any new foreign policy initiatives (unlike another LDP leader candidate, Shigeru Ishiba, who proposed an ‘Asian NATO’). His lack of foreign policy experience may give more weight to the National Security Secretariat and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs — which are responsible for implementing the FOIP vision — in foreign policymaking.

Second, it is highly unlikely that the new administration would weaken its commitment to the FOIP vision, endorsed by the United States and other Indo-Pacific partners. Although often overlooked, one of the great achievements of the Abe administration was getting the Trump administration to recognise the importance of FOIP. The Americans have now even adopted it as the US regional strategy.

This was significant, especially at a time when regional countries were increasingly concerned about whether the Trump administration would be committed to engaging with Asia and the Pacific. Aside from the United States, other regional powers such as Australia and India have welcomed the FOIP vision and agreed to cooperate to realise it. Given the United States and others continue to endorse the FOIP vision, and as long as Suga considers the US–Japan alliance a top priority in Japan’s foreign policy, there is little reason for Japan to turn.

Third, the FOIP vision has been increasingly institutionalised in the Japanese foreign policy apparatus. For example, Japan’s National Defense Program Guidelines for FY 2019 and Beyond stressed that: ‘In line with the vision of [FOIP], Japan will strategically promote multifaceted and multilayered security cooperation, taking into account [the] characteristics and [situation in] each region and country’.

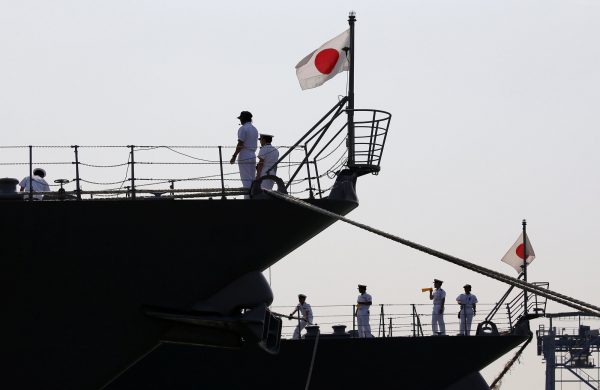

Japan’s Ministry of Defense (MoD) also created an Indo-Pacific division in the Defense Policy Bureau to address issues related to ASEAN and the Pacific. The MoD also published a six-page pamphlet: Achieving the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)’ Vision: Japan Ministry of Defense’s Approach.

It is uncertain when the new cabinet will announce its new National Security Strategy (NSS), reflecting developments that have occurred since the arrival of COVID-19. Still, it seems reasonable to assume that the pursuit of the FOIP vision, as well as Japan’s COVID-19 response, will feature prominently in Japan’s new NSS.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Japan’s FOIP vision has gradually evolved over the past decades by reflecting the changing geostrategic reality in the region. Japan’s strategic focus on both Australia and India, for example, started as early as the 2000s when China’s regional presence began to grow rapidly.

Even the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) government of 2009–2012 tried to enhance Japan’s security cooperation with both Australia and India, despite having problems with the United States over its plan to relocate a US military base in Okinawa.

Both the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) and Information Security Agreement (ISA) between Japan and Australia were concluded under the DPJ administration. In December 2009, then prime minister Yukio Hatoyama (2009–10) visited India and released a joint statement with the Indian prime minister at the time, Manmohan Singh, titled the ‘New Stage of Japan–India Strategic and Global Partnership’. The Japan Self-Defense Forces and the Indian Navy subsequently held their first joint bilateral naval exercise in June 2012.

It was former prime minister Yoshihiko Noda (2011–12), also DPJ, who cited the ‘rule of law’ in his speech at the UN General Assembly in 2012 as the guiding force for Japan’s foreign policy for the first time in its history.

Japan also supported regional connectivity and infrastructure development well before the beginning of the second Abe administration. In this sense, FOIP — whether a ‘strategy’ or ‘vision’ — is something that comprehensively tied together Japan’s existing regional policies, rather than something that emerged out of the blue.

Whether Japan likes it or not, China will continue to rise in the coming years. There is no option for Japan but to cooperate with Indo-Pacific powers such as the United States, India and Australia, as well as European countries, to maintain a desirable regional power balance that is necessary to manage Japan’s relations with China. This has become increasingly imperative as China increases its military activities in the region, including in the seas surrounding Japan. It seems reasonable to assume that the new Suga administration, and perhaps his successors as well, will continue to promote FOIP as Japan’s vision for a stable regional order.

Tomohiko Satake is a senior fellow at the National Institute for Defense Studies, Japan.