This shouldn’t be a surprise, as membership of ASEAN strengthens the power of member states’ executive branches. It is the heads of government and their representatives, irrespective of the nature of the regime they represent, who attend the organisation’s substantive events.

It is only when regional organisations create countervailing bodies of power, such as an elected regional legislature or independent intra-regional bodies with powers, that this executive power is challenged. For better or worse, such countervailing powers — a parliament, a human rights commission with powers of compliance, or an even more hypothetical arbitration tribunal — do not exist in Southeast Asia.

What, then, are the benefits of ASEAN membership? They are certainly much greater than those of non-membership. The recent ASEAN and related virtual summits organised by the association’s Vietnamese presidency confirm the impression that there are six: that of enhancer, legitimiser, socialiser, buffer, hedger and lever of their role in regional and international affairs.

As an enhancer, ASEAN reinforces the sovereignty of individual member states. It is not an instrument to check the power of its members’ executive branches, but instead serves to balance the competing demands of individual member governments. In performing this role, ASEAN is able to promote its centrality as the architect and conductor of international relations at the regional level. This enhancer aspect is reinforced by the ASEAN principle of non-interference as the major, informal rule that governs membership.

The enhancement of sovereignty is facilitated by ASEAN’s legitimisation of the diverse collection of political regimes found in Southeast Asia. When Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia joined in the late 1990s, this was largely and correctly interpreted as marking the end of the Cold War in Asia. But it was more than that. By ‘coming in from the cold’, their authoritarian regimes obtained respectability on the international scene.

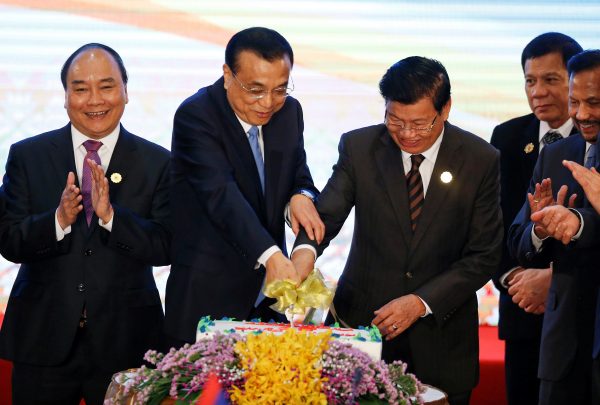

As an arena for intra-regional socialisation, ASEAN not only provides a mechanism for its much-vaunted consensus approach but also fosters ritual — hand clasping at its forums, for instance — that enables the projection of an image of a happy club of like-minded participants. The agenda of the most advanced and consensual of ASEAN’s three pillars — the ASEAN Economic Community — provides political space for peer pressure towards the engagement with the global economy that ASEAN’s open regionalism model seems to provide.

While these membership advantages link to domestic circumstances and Southeast Asian contexts, others have wider geopolitical importance.

ASEAN acts as a buffer against criticism, both intra-regionally and from external powers. Prior to Myanmar joining ASEAN in 1997, the Muslim-majority countries of Indonesia and Malaysia dished out unrelenting disapproval for Myanmar’s treatment of its Muslim minorities. Yet since joining, the criticism has softened, despite such a dramatic deterioration as the 2017 systemic terrorisation of millions of Rohingya.

A level of solidarity in the club reduces internal criticism within it. This also spills over into relations with external parties. In perhaps a caricature of Asian family tradition, the ‘black sheep’ benefits from the aura provided by the more respectable members. ASEAN is greater than the sum of its parts and external criticism of one member can be diluted by it being borne by all ten members.

The hedging benefits of membership provide intra-regional solidarity to international balancing strategies pursued by individual Southeast Asian countries. Within the trope of ASEAN centrality, various domestic forms of hedging are given a multilateral dimension that increases state capacity to negotiate geopolitical dilemmas, such as the minefield that is the US–China rivalry. ASEAN is, after all, a respected entity on the international scene and is highly capable of finding investors. In the power rivalry context, accepting and promoting ASEAN centrality is the convenient default option.

This is the basis of ASEAN membership acting as a lever for fund-raising and other forms of international support. According to the ASEAN Secretariat over the years, it would appear that at least two-thirds of ASEAN-related projects are financed by third parties such as China, the European Union, the United States and Australia.

ASEAN membership provides the advantages of mini-lateralist, inter-governmental regional integration, without requiring any diminution of national sovereignty that other supra-national, institutionalised forms of regional integration require.

ASEAN demonstrates you can, indeed, have your cake (or more appropriately mutabak) and eat it too.

David Camroux is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Center for International Studies (CERI), Sciences Po, Paris, and a Professorial Fellow at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. He is a former Dissemination Coordinator for the CRISEA project of the EU’s Horizon 2020 Framework Programme on Southeast Asian regional integration.