The Quad presents itself as a regional problem-solver, but it cannot escape the perception that its members are united by their problems with China. From Southeast Asia’s perspective, growing US–China tensions risk dividing the region. ASEAN needs to adapt to this changing environment.

For all of former US president Trump’s sabre-rattling against China, his unilateral and impulsive approach to foreign affairs hindered any multilateral action from US allies. Trump’s legacy may have hardened the US posture towards China, but President Joe Biden’s approach poses a more consistent challenge to China’s growing regional assertiveness.

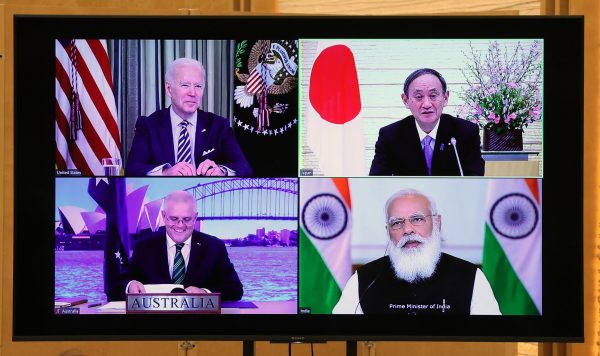

If there was any doubt that Biden would pick up where Trump left off, this was put to rest in Anchorage, Alaska in March, when his administration met with senior Chinese officials for the first time. Each side traded undiplomatic barbs and criticisms. The Quad will be more sustained this time because positions have also hardened in the other Quad capitals of Canberra, New Delhi and Tokyo. Perceptions of China have converged in recent years and the country is now largely seen as a threat.

The Spirit of the Quad statement describes the agenda as ‘inclusive, healthy, anchored by democratic values, and unconstrained by coercion’ — a contrast to the more ambiguous ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’. It promises institutional stability with the creation of expert working groups, regular foreign minister meetings and a leaders’ summit by the end of 2021. Stated challenges included COVID-19 and its economic impacts, climate change, the maritime order and the crisis in Myanmar.

The unstated hope is that by serving the interests of uncommitted states, the Quad may blunt Chinese assertiveness.

By contrast, Chinese multilateral engagement consists of a hub-and-spoke system with China at its centre. Each partner bilaterally connects with Beijing. While China engages with these partners’ multilateral projects when it suits it — such as ASEAN’s Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership — most of the conflux of activities goes through Beijing. This structure gives China greater leverage, but for this reason, China remains the least trusted major regional power.

The relative weakness of ASEAN members as small states was once an advantage that gave the organisation centrality. But this was predicated on the condition that no major power sought to assert dominance over the region. With the rise of China and the return of the Quad, this condition is evaporating as major powers seek regional influence and leadership.

ASEAN states have repeated their desire not to choose between the United States and China. Their voices are being sidelined by the national interests of both powers, driving them towards a critical moment of choice.

But there is another possibility. As antagonisms rise between the great powers, ASEAN itself can become not merely a platform for engagement, but an alternative course of action. ASEAN offers the potential to avoid a binary choice, but to do so it must become more effective at problem solving.

For example, US concerns about China’s dominance in the Mekong led to the Mekong–US Partnership, directly comparable to the Lancang–Mekong Cooperation. While rivalry could develop from these two competing institutions, ASEAN has an alternative: the ASEAN Mekong Basin Development Cooperation (AMBDC). Reviving the AMBDC and insisting that minilateral arrangements work through ASEAN’s multilateral structures may be needed to blunt divergent interests.

ASEAN states must also take raising governance standards in such projects seriously, to avoid both corruption and capture by sub-national interests that may lead them into messy dependencies or commitments to external actors. Just as some Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects have been multilateralised through institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Quad projects must also be multilateralised, potentially bringing ASEAN members in if funds are insufficient.

Some argue that ASEAN’s ‘fundamental purpose is not to solve problems but to manage mistrust and differences among its members’ yet the US–China rivalry not only threatens regional stability but ASEAN’s unity itself. If great power influence cleaves its members, the damage will be far greater. For better cohesion, ASEAN needs to find a stronger common purpose and look beyond diplomatic-level problems to assert its relevance among its people.

Some may caution against demanding too much from ASEAN, but the region is only of interest to great powers because ASEAN states have grown rapidly. Like China, the capacity of ASEAN states will continue to transform as they develop and their people’s aspirations and expectations grow. ASEAN should stop playing the poor dependent and start demonstrating the superiority of its methods — or risk being sidelined.

Joel Ng is a Research Fellow in the Centre for Multilateralism Studies at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.