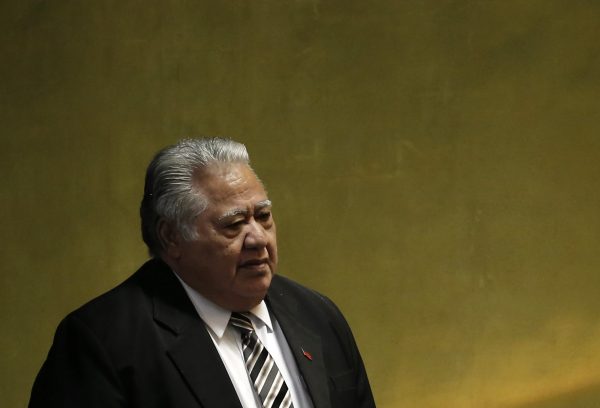

Yet in an election held on 9 April 2021, the result was a dead heat, with both the HRPP and the new FAST party (Fa’atuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi) tied with 25 seats each, and the balance in the 51-member parliament held by an independent. The position of the 75-year-old HRPP leader Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi — who has held office as Prime Minister for the past 23 years — looks decidedly shaky.

Malielegaoi’s troubles stem from a schism in his HRPP over laws passed in December 2020 that removed the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction over appeals from the Land and Titles Court concerning disputes over land ownership and matai titles. The effect of the laws is a division of the judicial apparatus into two parallel systems, one dealing with criminal matters and the other with customary law.

In protest, Deputy Prime Minister Fiame Naomi Mata’afa — who is the daughter of Samoa’s first post-independence leader — resigned her post, as did several other HRPP MPs. They accuse the Prime Minister of flouting the rule of law. Malielegaoi responded that his opponents are captives of ‘palagi’ (foreigner) thinking. He has launched a commission of inquiry into what he calls their ‘treasonous acts’.

The dispute reveals a tension between customary and imported law that has troubled Samoa since it secured independence from New Zealand in 1962. The 1962 constitution restricted the right to vote and contest elections to the mostly male holders of traditional matai chiefly titles. In 1990, the HRPP opened the franchise to all citizens over 21 years of age, but in a bow to tradition preserved the matai-only rule for candidates.

Village councils were left with considerable autonomy, for example to ‘banish’ unwanted individuals or those who embrace new religious faiths, actions that Amnesty International fears may no longer fall foul of the Supreme Court and the constitution’s human rights provisions.

With secure majorities, Malielegaoi’s governments acquired a reputation for audacious reform. A 2009 law changed the side of the road on which Samoans drive from right to left, in order to facilitate cheaper car imports from Japan. Samoa relocated the international dateline to its east in 2011, so as to ease business by having a common working week with Australia, New Zealand and Asia.

But the HRPP government handled a 2019 measles epidemic poorly after it rejected earlier appeals by public servants to launch a vaccination campaign. The epidemic killed 83 people. Although Samoa has been free of COVID-19, its tourism industry has collapsed. The Asian Development Bank expects its economy to contract by 5 per cent in 2020 and 9.7 per cent in 2021.

The HRPP has a ruthless streak. A 2006 law withdrew recognition from parties with less than eight members, and outlawed side-switching on the floor of parliament. In 2009, the opposition Tautua Samoa Party had its seats declared vacant, though the courts ruled that action unlawful. Harsh laws discriminating against small opposition parties will be of no avail against FAST or its leader Fiame Naomi Mata’afa, since they have almost half the parliamentary seats. Unsurprisingly, given Samoa’s recent history of ever-increasing electoral litigation, Malielegaoi has declared his intention to dispute the election results in court.

The HRPP fought a lacklustre campaign, expecting triumph on the basis of past glories. The party performed strongly on the main island of Upolu, where the capital Apia is located. FAST fared better on Samoa’s second largest island, Savai’i. That vote distribution reflects the HRPP’s long dominance over the state, and its strong support among civil servants. FAST’s strength outside the capital owes much to the influence of the Congregational Christian Church. A decision to tax church donations strengthened anti-government sentiment among the country’s many devout Christians.

The HRPP fielded multiple candidates in many constituencies, a strategy that worked reasonably well when the opposition was minute and when there were often two seats for each district. Yet for the 2021 election, Samoa switched to a single-member first-past-the-post system. The HRPP ran multiple candidates in many constituencies, and lost to FAST owing to split votes. The HRPP won on the popular vote, but it lost its majority owing to its failure to field single candidates in key marginal constituencies.

Jon Fraenkel is Professor of Comparative Politics at Victoria University of Wellington.

There is one clarification here.

The “tax on church donations” is not well explained here. It is a tax on the donations to the clergy for their personal income. All but one church, the Congregational Christian Church of Samoa (EFKS) has opposed this law. The EFKS happens to be the largest denomination in Samoa (30% of the population), so EFKS clergy and a good proportion of its congregations were outraged. The idea of the tax is because many clergy (but mainly EFKS ministers) earn significant untaxed incomes. The government saw it as simply a matter of a fairer tax system. The EFKS saw it as a direct attack on their beliefs.

This was the first election where many EFKS ministers openly campaigned for a particular political party – FAST in this case.