COVID-19 has put the size of the climate challenge into perspective. Shutting businesses, grounding airplanes, garaging cars and closing factories during COVID-19 reduced global carbon emissions by about 7 per cent. This helps illustrate the size of the climate challenge. If we are to avoid a 1.5 degree increase in global temperatures, we need to achieve this same fall in carbon emissions every year for 10 years.

Given that closing down the global economy every year isn’t an option, governments across the world will need to fundamentally transform their economies if they are to reduce carbon emissions sustainably and do so at the least possible cost to people’s livelihoods. Other than putting a price on carbon to bring about these changes, achieving this will require new investment in green infrastructure and technologies, and a lot of it.

The annual production of electric vehicles will need to increase tenfold to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030. The number of charging stations will need to increase 31-fold. Up to 2 per cent of the United States will need to be covered in solar panels and wind farms, according to one estimate. Mining companies will need to expand their production of the minerals that go into these technologies by more than 500 per cent.

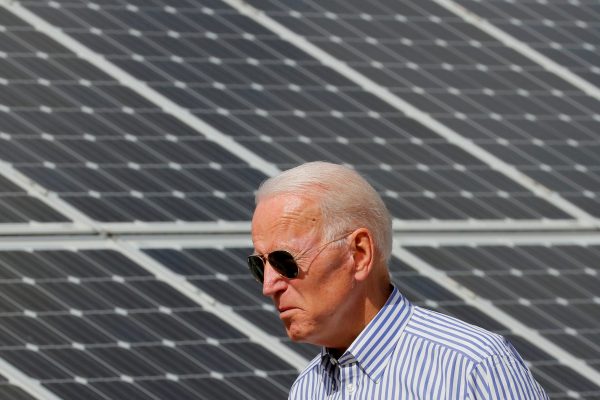

Unless Biden’s global climate change agenda includes practical ways to unlock trillions of dollars of private finance, he will struggle to achieve his climate goals.

Economically, most of the world’s governments have nowhere near the fiscal space to undertake the necessary level of investment. This is especially true for developing economies due to high levels of foreign-denominated debt, undeveloped financial systems and weak monetary policy frameworks. It’s also true for most European countries which have limited fiscal space due to their lack of independent monetary policy, their shared exchange rate and EU-wide fiscal rules on debt and deficits.

Politically, Biden needs to appeal to both sides of politics, particularly given his thin majority in Congress and the politically diverse group of G20 countries he needs to win over. A Green New Deal might be appealing to the US political left, but the political right wants solutions that involve the private sector.

The maths of climate change mean that investment by the private sector will not only be important; it will be critical. Our ability to address climate change hinges on the ability of the world’s financial systems to direct sufficient finance to where it is needed to exit from a carbon-dependent economy.

Luckily, there are practical things the Biden administration can do at the global level to boost private investment in combating climate change.

First, Biden could lead reform of global capital rules around the buffers that banks are required to hold to withstand shocks. A growing body of research shows that borrowers with strong environmental credentials are less likely to default. This means that those loans, and the securities underpinned by those loans, are safer than their environmentally-unfriendly counterparts. If the global capital rules took this into account, banks would be incentivised to issue more green loans, hold more green debt on their balance sheets and thus direct more finance to green initiatives while at the same time strengthening financial stability.

Second, Biden should lead a push to standardise what constitutes ‘green’ in the context of green finance. There are plenty of metrics and indicators out there, but they rarely align. This is a problem. The nature of financial capital means these indicators need to be consistent and agreed at the global level, if global rules are to be developed in this area. More and more countries are developing their own indicators — from Canada and China to Singapore — but consistency will be critical if global markets are to function effectively.

In our lead article this week, Robert Stowe assesses the claim that US leadership is back on climate change. Although Biden has done a lot — from re-joining the Paris agreement, implanting a climate-focused fiscal stimulus, signing a series of executive orders to reduce emissions and hosting a global summit on climate change — some see the US return as more like the truant student returning to class than the return of a great king to lead battle. The fear, well-founded, is that Biden’s switch is merely the latest episode of US zigzagging on climate policy — hardly the stable commitment required for resolute leadership.

‘President Biden holds only razor-thin majorities in Congress, putting legislation that will be required to achieve much of his ambitious climate agenda out of reach’, warns Stowe. ‘The President’s green infrastructure plan is already in trouble in Congress. Biden may lose even this slim congressional majority in the 2022 midterm elections, and potentially the presidency itself in 2024 to a Trump-like Republican, putting the executive action he will have been able to undertake at great risk’.

One major objective of Biden’s climate summit was to provide a forum for major-emitting countries to submit more ambitious pledges under the Paris agreement. A number of leaders announced new commitments, including the leaders of South Korea and Japan. China and India, the world’s first and fourth-largest emitters, however, did not, although China had made the 2060 net-zero carbon emissions commitment sometime before.

To win these countries over, Biden needs to offer them practical solutions that help finance the climate investment they desperately need. Limited fiscal space, challenging domestic politics and a politically diverse G20 means catalysing private finance could be a critical way to make progress beyond mere rhetoric.

Success in fighting climate change will hinge on whether our financial system is up to the task. Without key reforms that recognise the real value of green investment, it won’t be.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.