Over the last half century, Japan–Taiwan relations tended to focus on economic relations and people-to-people exchanges with weak political and security relations — but this may be changing. As rhetoric emphasising Taiwan as a potential flashpoint of US–China conflict has increased, the Suga administration in Japan has increasingly shown its support for Taiwan.

At the US–Japan leaders’ summit in April, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga and President Joe Biden underscored ‘the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait’ and encouraged ‘the peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues’. This was the first such reference to Taiwan in a US–Japan joint leaders’ statement since 1972 when Japan and China normalised their diplomatic relations. Japan similarly referred to ‘peace and stability’ across the Taiwan Strait in the US–Japan 2+2 joint statement in March, the Japan–EU joint statement in May, and the Japan–Australia 2+2 joint statement and Carbis Bay G7 communiqué in June. The latest edition of Japan’s Defence White Paper included an increased focus on Taiwan.

The Suga government also held party-to-party talks between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and Democratic Progressive Party in late August. The talks included a heavy focus on security issues as well as discussion of planned investment in Japan by Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer TSMC and cooperation on semiconductor chip supply chain resilience. While such a party-to-party meeting is within the bounds of the ‘one China’ policy, the move nevertheless irked Beijing.

The Japanese and Taiwanese people have come to see each other as friends who will help out in times of need. Taiwan was the largest donor to Japan after the 3/11 earthquake–tsunami–nuclear triple disaster. Japan is now repaying the favour. A poll by the Nikkei Shimbun soon after the Biden–Suga summit in April showed that nearly three-quarters of respondents supported Japan’s engagement for the stability of the Taiwan Strait. After China suspended imports of Taiwanese pineapples, ostensibly due to a biological pest, Japan stepped in to fill the gap increasing its imports of the fruit from the island eightfold between March and June compared with the same period in 2020. Nationalist Japanese politicians competed to share their Taiwan pineapple photos on social media. Japan has also donated over 3 million AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines to Taiwan.

Yet as Japan navigates its increasing closeness with Taiwan it will need to finetune a delicate balance. This means maintaining the deterrence power of the US–Japan alliance, demonstrating Japan’s commitment to burden-sharing to keep the United States engaged while working within the framework of Japan’s Constitution, and avoiding antagonising China in ways that would unnecessarily make conflict more likely.

As Sheila Smith explains in this week’s lead article, which launches the latest edition of East Asia Forum Quarterly, a contingency scenario across the Taiwan Strait would constitute a credibility test for the US–Japan alliance. Because of Japan’s southernmost islands’ proximity to Taiwan and the fact that Japan ‘hosts a considerable array of US military forces’ in Okinawa — ‘making it a likely staging area for any US assistance to Taiwan’s defences’ — any conflict over Taiwan will have a major impact on Japan’s security.

‘Regardless of the intensity of such a confrontation’, Smith explains, ‘Tokyo would be faced with difficult decisions about how Japanese and US forces would cooperate in response’. Specifically, ‘Japan’s role would likely involve two distinct actions. First, Japan would be asked to provide support for US operations. Second, Japan’s Self-Defense Forces would need to consider how best to defend Japanese territory during a conflict’.

Since the international criticism that Japan faced for its so-called chequebook diplomacy during the 1990–1991 Gulf War, it has sought to avoid another Gulf War shock that could undermine credibility in the US–Japan alliance. Back then, political gridlock in Tokyo — coupled with the lack of a legal framework governing overseas dispatches of its Self-Defense Forces (SDF) — saw Japan unable to respond to US requests for a boots-on-the-ground contribution as part of its operations to liberate Kuwait from Iraq under Saddam Hussein.

While Japan is showing a proactive stance toward Taiwan both out of a sense of friendship with the island as well as to shore up the US–Japan alliance, it is crucial that Tokyo be frank with Washington and not oversell what sort of contributions the SDF can make under its limited recognition of collective self-defence based on its 2015 security legislation. Proactive consultations with the United States about the roles Japan will — and will not — play in a contingency scenario will go a long way towards preventing a crisis both by maintaining the alliance’s military deterrence power and by ensuring that the two allies are on the same page about the division of labour.

The new issue of East Asia Forum Quarterly (EAFQ), ‘Confronting crisis in Japan’, explores an array of potential and incipient crises, in addition to Sheila Smith’s analysis of the role of Taiwan in Japan’s foreign policy, that will confront Japan in the 21st century. This includes dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to properly embrace digital technology in governance processes, the conundrum of Japan’s Imperial succession, underwhelming ‘womenomic’ outcomes in the #MeToo era, the uncompetitive nature of its democratic landscape, and Japan’s broken relationship with South Korea. Whether it be in the sphere of social issues, domestic political economy or foreign policy, Japan’s capacity to manage ‘slow-burn’ crises will be the primary test for the country’s policymakers and citizens alike in coming years.

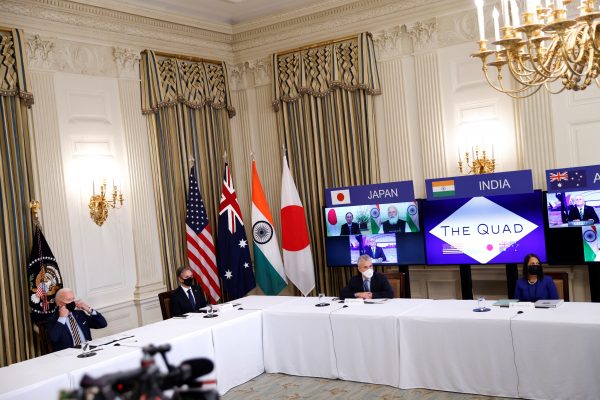

Meanwhile, EAFQ’s Asian Review section takes a sceptical look at whether the Indo-Pacific idea can meet the rising expectations that appear to be held of it. It also examines the devastating impact of COVID-19 on India, and how federalism affected its management of the crisis and public trust in government.

Join the ANU’s annual Japan Update conference online on Wednesday 8 September at which the latest issue of EAFQ will be launched.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.