In fighting communism, the United States extended its security umbrella to the region. This gave ASEAN members breathing space and allowed them to focus on economic growth and domestic stability. It also stimulated unity among Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines due to fear of being entangled in great power intervention. Aid and investment from Japan, a US ally and Asia’s then fastest rising economy, helped industrialise several Southeast Asian countries.

Now, China has displaced Japan as Asia’s largest economy and ASEAN’s largest trade partner. China’s GDP today is more than five times that of ASEAN’s combined. It spends five times more on defence. Unlike the Soviet Union, China is Southeast Asia’s immediate neighbour — a dragon breathing down its neck.

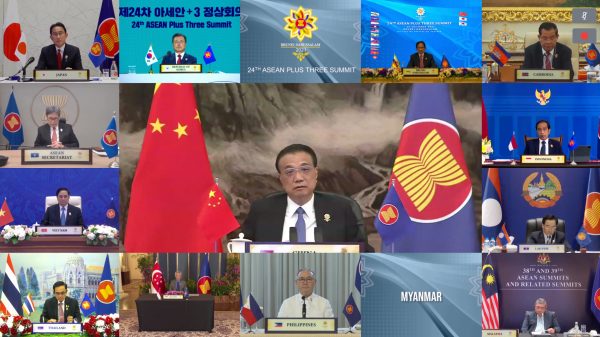

ASEAN’s capacity to offer a collective diplomatic response to the new geopolitics is under challenge. Membership expansion from the group’s original five states has made reconciling national positions difficult. Security threats have expanded from territorial conflicts and domestic rebellions to pandemics, climate crises, and terrorism, imposing new burdens on ASEAN’s limited resources.

The Quad and AUKUS are responses to the growing imbalance of power brought about by China’s rise. China’s anti-access area denial capability — backed by a growing inventory of advanced anti-ship and traditional ballistic, cruise missiles and submarines — diminishes the military edge traditionally enjoyed by the United States, making it difficult for it to intervene in conflicts close to Chinese territory.

Yet, anti-submarine warfare is a weak point for China. As a Rand corporation report notes, due to ‘marginal improvements to Chinese anti-submarine warfare capabilities, the US submarine fleet remains capable of doing substantial damage to China’s surface fleet’. This is where the submarine component of AUKUS assumes importance.

The Quad is more general and for that reason, of more ambiguous military value. According to SIPRI data for 2020, US defence spending was US$778 billion. Add to this the combined defence spending of the three other Quad members (Japan, India and Australia) and the result is a total Quad defence spending figure of US$927.5 billion, four times that of China.

But the Quad is not a military alliance and there is no certainty that all four members will act in concert in the event of an actual military conflict in the region.

It is unlikely that the US Indo-Pacific strategy will fly if it focuses too much on the Quad and AUKUS. History shows that military coalitions created to defend a region without regional participation remain weak or wither away.

The key test of the Quad and AUKUS is to be seen as a regional public good. At this time, the benefits of the Quad and AUKUS seem to be going mainly to members. The number of Southeast Asian nations in the Quad and AUKUS is zero. In contrast, China continues to provide infrastructure aid and trade to ASEAN, sometimes in more generous terms than other big powers.

While ASEAN’s normative policy of engaging all major powers still has value, it needs a more strategic approach to the new geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific. ‘Strategic’ here means a focused, overarching and long-term approach to preserve autonomy from both China and the United States, rather than allowing itself to be a strategic appendage to their competition.

ASEAN’s response to the old geopolitics was the Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN). While a ZOPFAN 2.0 may seem no easier to realise now than it was during the Cold War period, this should not stop ASEAN from developing some concrete confidence-building and transparency rules to govern military deployments. Such measures should be integrated into the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific to make it more robust.

ASEAN needs to develop a ‘responsibility to consult’ norm and hold its dialogue partners accountable when they make decisions affecting the stability of Southeast Asia without prior consultations.

ASEAN policy experts should strengthen track II dialogues. Strategic dialogues about Southeast Asia today are often led by ‘experts’ who are only superficially interested in or knowledgeable about Southeast Asia.

Finally, it is important for ASEAN to reclaim the Indo-Pacific idea. Names matter. While the term ‘Far East’ came from imperialists, ‘Asia’ from nationalists, ‘Asia Pacific’ from economists and ‘East Asia’ from culturalists, the ‘Indo-Pacific’ seems to be driven largely by military-strategists.

ASEAN is not united when it comes to the Indo-Pacific, Quad and AUKUS. But a more unifying alternative to the military-strategic notion of the Indo-Pacific might come from the historical Indian Ocean network. Centred on the Indian Ocean but linking the Western Pacific, Africa, the Middle East and the Mediterranean, it was the largest and most open maritime trade network in the world before European colonisation.

It had no hegemon and Southeast Asia remained at the heart of the network. Those fearful of the Chinese tributary system redux should be reminded that the ‘maritime Silk Road’ is at best historical fiction — Indian cotton, Southeast Asian spices and Hindu-Buddhist religious ideas and objects transiting between India and East Asia, rather than silk, were the main trading items in the Indian Ocean. Unlike in the East Asian tributary system, in the Indian Ocean system, China was at most a large frog in a much larger pond.

While history does not repeat itself exactly, it offers alternative ideas and models for building world orders.

Amitav Acharya is Distinguished Professor of International Relations and The UNESCO Chair in Transnational Challenges and Governance at the School of International Service, American University. His latest book is ASEAN and Regional Order: Revisiting Security Community in Southeast Asia (2021)