It was not just the country with the highest anticipated growth in 2022, 9.0 per cent for India’s April 2022-March 2023 (FY23) financial year. It was also the only major economy where projected growth was raised, and that by a sizable 0.5 percentage point. Equally striking is that the Fund raised its 2023 India forecast, also by 0.5 percentage points, to 7.1per cent, also the highest growth of any G20 economy.

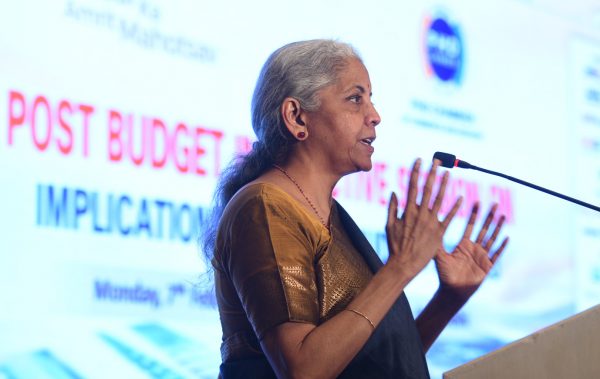

The Fund’s forecast was made before Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented India’s federal budget for the 2023 financial year in a speech to Parliament on 1 February. The minister’s speech is the tip of a very large iceberg. The budget speech provides the government’s political narrative — but the economic fine print is in the Finance Bill. This is laid before the parliament as the minister speaks and is simultaneously revealed to a horde of analysts and journalists. Pre-budget secrecy is taken very seriously in India, as some tax proposals have immediate effect. Known leaks are rare.

As per hallowed custom, shortly after parliament adjourns for the day, the finance minister and her officials hit the media to explain the financial engineering and policy logic behind their proposals. India’s competitive news channels feature commentary by a broad range of experts throughout the day and into the evening. Instant analysis is followed by more thoughtful commentary in newspapers in the days that followed. Amartya Sen’s characterisation of ‘the argumentative Indian’ was on glorious display, even more impressive for being so concentrated in time.

Economic growth in the financial year now ending (also 9.0per cent according to the IMF) represents a rebound from the sharp decline in the previous year, with overall output only now returning to pre-pandemic levels. As such the FY23 budget follows two years of economic growth lost to the COVID-19 pandemic, with associated scarring of the labour market and lost years of schooling for the young.

The budget was presented on the eve of important elections for state assemblies including India’s most populous and politically influential state, Uttar Pradesh (UP), whose state assembly is currently led by an active, but controversial, Chief Minister from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Yogi Adityanath. Results are to be declared on 10 March. A return to power by the BJP in Uttar Pradesh would validate the Chief Minister’s political tactics and development policies and would provide the party and Prime Minister Modi with considerable momentum for the next parliamentary election in 2024.

India faces a complex geopolitical environment in its immediate neighbourhood. There has been no progress on its Ladakh border dispute with China where both Chinese and Indian troops were killed in combat in June 2020. The chaotic withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan in August 2021 and the reinstallation of a Taliban government were setbacks to India’s development efforts in Afghanistan, raising the threat of terrorist blowback across India’s border with Pakistan in the Kashmir Valley.

China’s superior resources and its economic and strategic interests make it an increasingly aggressive competitor in India’s ‘near abroad’. China’s closest relationship is with India’s traditional adversary, Pakistan, where the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) forms a central axis of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. China is also increasingly influential elsewhere in South Asia, including in Sri Lanka, Nepal and Myanmar, although perhaps somewhat less so in Bangladesh. In addition to these challenges, the budget also needed to accommodate massive uncertainty in the global outlook for commodity prices, inflation, interest rates and capital flows.

Four broad themes dominated the budget. First, conservative fiscal revenue estimates. Second, expanded allocations for capital formation — particularly for highway construction, but also for other physical infrastructure. Third, a bet that, in contrast to its dismal experience in the 1970s and 1980s that this time, India can reconcile tariff protection with integration into global value chains. And fourth, a belief that India’s future lies, above all, in the whole-hearted embrace of technology, from taxing cryptocurrencies to introducing a central bank digital currency and a lot else besides.

This budget is much more muted on the reform areas featured last year. These include agriculture, where the government was forced by farmers (including in parts of Uttar Pradesh) to repeal legislation passed last year, labour laws, privatisation, and reform of electricity distribution, critical for India’s green aspirations.

The budget thus represents two significant political bets. First, that there is sufficient patience and resilience within India’s enormous informal employment sector for a significant step up in public investment to improve the jobs outlook without the government suffering serious political consequences. Second, that the initiatives of this budget will bear full fruit before the next parliamentary election.

Only time will tell if these judgements are well-founded, and whether they will produce a third year (and more) of fast growth as projected by the IMF and signalled by the stock market. For now, what one can say with some certainty are three things.

First, India is closing out 2021–22 in better economic shape than seemed likely in the first quarter of the year. Second, despite the humanitarian devastation wrought by COVID-19, animal spirits seem to be reviving India’s private sector. Third, the relative absence of widespread civic unrest over the last two years suggests that the political compact between the rulers and the ruled has held firm despite the enormous stress placed on the citizenry. For this, India’s robust democracy can take some of the credit.

Suman Bery is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. The views expressed are the author’s own.

Not unless India figures out how to include small urban and rural india in prosperity. Unless inter-district commerce becomes a reality – India will continue to drag its feet. I am no economist but I know that there is a way to bring 70% of left out india, within the main stream.

Thanks